Women Apart

By James Tobin

The recent tendency to formalize social life at Michigan … strikes me as under-cutting the intellectual aspect of co-education.– Alumna Ruth Weeks

-

Chapter 1 The Questionnaire

In 1924, a widowed woman in her sixties named Ora Thompson Ross – living alone after raising three sons, all of them launched into business as sellers of bonds and securities in big cities far away – sat down at her typewriter to fill out a questionnaire from her alma mater.

Mrs. Ross had spent nearly all her life in the small town of Rensselaer, Indiana. The exception was her four-year term as a student at the University of Michigan in the early 1880s.

The questionnaire had come in the mail from the U-M Alumnae Association. Fifty years had passed since the first women students graduated from Michigan. Now the University was asking all female graduates to send back notes about “the extent of their influence and service” since leaving Ann Arbor – their occupations, achievements and “public offices held.”

In the blank for “occupation,” Mrs. Ross typed: “Home keeper.”

As for public offices, she said she had been a trustee of the Rensselaer Public Library for 25 years; an officer in the Indiana League of Women Voters; and chair of the Women’s Section of the Jasper County Council of Defense during the World War.

The final question was: “Won’t you add a few of the outstanding memories of your college days?”

Mrs. Ross knew all about the fine new women’s dormitories at Michigan – Helen Newberry, Martha Cook, Betsy Barbour – and the sororities and “League houses” with the house mothers checking their watches and peering over girls’ shoulders and making sure that “gentleman callers” got no farther than the “social parlor.”

Then, thinking back on the early years of co-education at Michigan, Mrs. Ross wrote: “I cherish the memory of … the free and uncensored existence led by women students in those days. The idea then was that a young woman old enough to go to college was old enough to be self reliant. They seem so much younger now!”

-

Chapter 2 A Stimulating Atmosphere

In Ann Arbor, staff members opening completed questionnaires at the Alumnae Association read more than a few remarks like Mrs. Ross’s. All came from women who had gone through Michigan without supervision, living on their own, often with male classmates down the hall.

Ruth Weeks, who had graduated in 1913, just a decade before the survey, remembered “the absolute freedom of the Ann Arbor life – an informal social life of the students in which men & women of congenial interests met & mixed.” That had been “the chief value of the university,” she said, and “the recent tendency to formalize social life at Michigan … strikes me as under-cutting the intellectual aspect of co-education … I have heard many a Michigan girl say, ‘The men I knew educated me.’”

“A healthy and hearty relationship and honest rivalry between young men and women exists,” wrote a graduate of 1876. “It is a stimulating atmosphere and develops in good stock a strength and independent balance which tell in after life.”

It was not that way anymore.

Year by year, the situation of women at Michigan had been transformed. The change was well underway by 1900 and quite complete by 1920. Where women students had once fended for themselves and mixed freely with men, they now lived in a segregated, regulated and tightly supervised sphere marked “Women Only.” The pattern of women’s lives outside the classroom that would prevail until the 1960s and ’70s had been set.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Women and men in an Ann Arbor boarding house in 1902. One woman who graduated in that era recalled: “The intermingling of boys and girls in the same home brought about a democratic and broadminded outlook upon life."Chapter 3 “The Intermingling of Boys and Girls”

In the early years of co-education at Michigan – the 1870s and ’80s – women students enjoyed a striking degree of freedom. With the early contingents of women numbering only in the dozens compared to more than 1,000 men, the male majority regarded the newcomers as a curious but inconsequential minority.

Some on the all-male faculty applauded their presence. Some opposed it. But either way, professors left women students to lead their own lives outside the classroom. In the era before dormitories, women and men alike found their own housing in Ann Arbor’s dozens of boarding houses, and the sexes often broke bread together under the same roof, coming and going as they pleased.

“The intermingling of boys and girls in the same home brought about a democratic and broadminded outlook upon life,” recalled Genevieve O’Neill, who earned undergraduate and graduate degrees at the turn of the century, “as well as mutual understanding between the sexes.”

“I never saw a girl ‘fall,’” she said, “or knew a boy to demean himself by attempting to lead a college girl astray.”

But as the proportion of women on campus marched upward – 10 percent of students by 1880, then 20 percent by 1890 – their situation drew increasing attention, especially from adult women who thought changes were needed.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Students participate in gymnastic exercises in Barbour Gymnasium, the first building at Michigan built expressly for women.Chapter 4 Independent But Isolated

A renowned feminist issued the first call for change, in a speech delivered in Ann Arbor in 1890.

The speaker was Alice Freeman Palmer, the University’s most distinguished woman graduate to date. She had been one of the earliest female students, and she became the first female president of the all-women Wellesley College at the age of only 26. She would soon be appointed the first dean of women at the new University of Chicago. No voice had been stronger for the cause of women’s education.

But while Palmer valued the independence that women had enjoyed at Michigan so far, she also believed something was missing. Women students, she said, needed closer association with each other and with older women who might serve as role models, chiefly wives of male faculty members. The girls needed an organization to bring them together and promote their interests.

Many agreed. Independence was good, but its flip side – isolation – had left too many women students lonely and unhappy.

“We frequently hear of girls who have been here in Ann Arbor through the entire four years of the college course, being good faithful students, and yet going away without having made any friends,” wrote Mary Markley, a graduate of 1891 – yes, that Mary Markley – “or being one whit the richer for the superior social advantages which must always be found in a university town.”

The upshot was the organization of a Michigan Women’s League. Sarah Caswell Angell, the wife of President James Burrill Angell, presided at the first meeting of 18 students and three faculty wives. The group soon swelled in membership and influence.

In later years, many women students spoke fondly of their friendships with faculty wives. But the wives were not exactly progressive. One year, when the student president of the League invited the feminist leader Susan B. Anthony to address the group, she got a sharp talking-to by faculty wives. They said the student should have checked with them first, since the invitation to Anthony might look like an endorsement of Anthony’s movement for women’s rights, including the right to vote.

By the mid-1890s, with the new Waterman Gymnasium filled mostly with men, the League secured support and funding for a separate gymnasium for women. Barbour Gymnasium, completed in 1896, became the center not just of women’s athletics but of all women’s activities on the campus, with meeting rooms and an auditorium, not to mention a dozen bathtubs much valued by women accustomed to sharing a single washbowl in a boarding house.

The construction of Barbour Gym was hailed as a milestone for women at Michigan. But it also represented a large step toward a sphere separate from men.

And the gym housed an office with a new title on the door – “Dean of Women.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

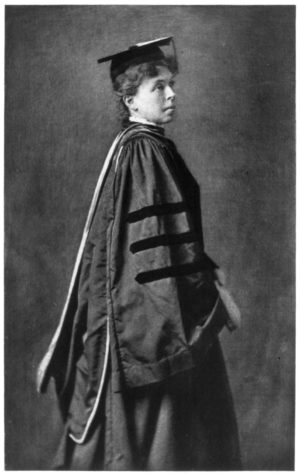

Alice Freeman Palmer (LSA 1876), one of Michigan's earliest women graduates, was a leading spokesperson for women's education. She was also among the first to call for closer and more formal associations among U-M women.Image: Library of Congress

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Myra Beach Jordan, the second dean of women, was the chief architect of a more segregated and regulated social sphere for women students.Chapter 5 For Women Only

President Angell had been uneasy about the idea of a dean of women, a new post at a number of schools that competed with Michigan for students. He thought the position might foster an atmosphere more like a girls’ finishing school than a university. But as the number of women students continued to grow, he felt the pressure of public opinion. Surely, it was thought, so many single young women on a campus teeming with men needed adult supervision.

Dr. Eliza Mosher, an 1872 graduate of U-M’s Medical Department, accepted Angell’s appointment as the first dean of women. (At her insistence, she also became the University’s first female professor. She taught courses in hygiene, a forerunner of the field of public health, in LSA.)

As it turned out, Dr. Mosher had little interest in her charges’ social lives. She focused on health and physical fitness.

It was Myra Beach Jordan (LSA 1893), succeeding Mosher as dean in 1902, who tightened the boundaries of the separate sphere for women.

Energetic and conscientious, Jordan made it her business to learn the name of every girl on campus. In her view, this new generation of “co-eds” were not only younger than the first women students but not as serious about their studies. They would need a stronger hand.

* * *

By the start of Jordan’s long term as dean (1902-1922), more than 700 women students were attending classes among some 2,800 males. Along with the men, all but the small number of women living in sorority houses were competing for space in Ann Arbor’s overtaxed rooming houses.

The houses themselves were getting an unsavory reputation. Reports of tainted water and poor sanitation were not uncommon. Many were crowded and run down. Not a few owners had reputations for either tyranny or negligence.

In 1905, the Michigan Alumnus voiced a rising concern. The editors wrote: “The time-honored custom of throwing the students of the University, men and women, or rather boys and girls, upon the good will, or tender mercies, of the townspeople for home and food has resulted in a system which, while it has been accepted with more or less equanimity by the residents and authorities of the University – because it has worked – has undeniably brought criticism upon the University.”

Dean Jordan was already working on it.

She instituted a system of certification. Rooming houses for women would receive the dean’s personal seal of approval if they were women-only; if they met standards of safety and sanitation; if a supervising “house mother” lived on the premises; and if male callers would be restricted to an approved “social parlor.”

The system was developed with the cooperation of the Women’s League, so the houses were soon called “League houses.” Year by year, more and more owners signed up to follow the dean’s rules, and by the time of the World War there were dozens of League houses in town.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Mosher-Jordan Hall, named for the first two dean of women, under construction in 1928.Chapter 6 “The Real Solution”

But that still didn’t solve the problem. There were still not enough sororities and League houses to provide quarters for the burgeoning numbers of women students.

The League houses begat the obvious next step.

“As this idea of group life and responsibility developed,” Dean Jordan wrote later, “all thinking Michigan women saw that dormitories were the real solution for living conditions.”

Many students agreed. “For anyone who has made a study of student life,” wrote the editors of the Michiganensian yearbook, “the need of better housing conditions is apparent.”

Again, the Women’s League took the lead, hiring two recent graduates, Myrtle White and Agnes Parks, to mount a campaign of educating alumni and soliciting donations for women’s dormitories. President Harry Burns Hutchins signed on. While White and Parks toured the country to speak with wealthy potential donors, Dean Jordan spread the word with visitors to the campus.

To their surprise, the idea of women’s dorms was no easy sell with alumnae who had gone to Michigan in the early years of co-education.

“It seems difficult to believe it possible now,” Myrtle White wrote from the vantage point of 1930, “but our first great problem was to convince the majority of our alumnae that halls of residence were needed at Ann Arbor.”

But the campaign hit on a winning theme: they would urge prospective donors to imagine their gifts to the University as tributes to their mothers.

That idea made a strong impression on the children of Helen Newberry, widow of a wealthy manufacturer in Grosse Pointe; on Levi Barbour, a Detroit real estate developer, the son of Betsy Barbour; and on William Wilson Cook, the native of Hillsdale, Michigan, who had become one of the wealthiest lawyers on the east coast.

When Myrtle Wilson suggested that Cook might honor his mother by giving money for a dormitory, Cook replied: “Little girl, that idea strikes a sympathetic chord in my heart. I’ll tell you now that I’ll give $10,000 toward this project, and it may be a great deal more. Tell your president to come to see me.” Wilson’s pitch would lead not only to the Martha Cook Building but to the Michigan Law Quadrangle, which Cook funded as well.

* * *

Within 10 years, four dormitories for women were built – the Helen Newberry Residence, housing 78 women; the Martha Cook Building (120 residents); Alumnae House (later Henderson House), built for women paying their own way through college; and Betsy Barbour House (80 women).

Each was run by a social director answering to Dean Jordan. Curfews were enforced. Rules of decorum were observed.

“By 1920,” wrote Ruth Bordin, a historian of U-M, “women’s role at Michigan was well set in the patterns it was to follow until the second feminist revolution in the late 1960s and 1970s … The organizational life of the university’s students, including athletics, student government, living quarters, and social and philanthropic organizations, were almost completely segregated by gender. Women and men students met only in classes, and then chiefly in the College of LSA, and in the dating game.”

Four much larger dormitories for women would follow – Couzens Hall (1925), built to house nurses and nursing students; Mosher-Jordan Hall (1930), named for the first two deans of women; Madelon Stockwell Hall (1940), named for U-M’s first officially enrolled woman student; and Alice Crocker Lloyd Hall (1949), named for the fourth dean of women.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

An image from the U-M Castalian, a student publication, in 1891.Image: The Castalian, 1891Chapter 7 Another Questionnaire

Many of the first women at Michigan had subscribed to principles of the earliest wave of American feminism. By the 1920s, that wave had led, after a long struggle, to the Nineteenth Amendment – votes for women – and now a new era of feminist thought and action was underway.

One of its adherents was Ruth Wood, who earned her B.A. in 1921 and a graduate degree in 1922. On her own Alumnae Survey questionnaire, she said just what she thought of the new sphere for women on the campus.

She excoriated “Michigan’s sentimental and antiquated attitude towards women. Her students … and her officers, can conceive of no relationship between men and women other than that sentimentally devout or quasi-sexual.

“Her publications reek of it, the managing of class affairs, frat functions, is controlled by it … Officers as well as students are unable to recognize professional intellectuality in women. Discrimination made in the medical school, and discrimination made against women for the faculty are two examples, infuriating beyond words…”

But it would be half a century before Wood’s view of the role of women would be taken up by a third generation of campus feminists, and force the coming of another new era.

For earlier stories of Michigan co-education, see:

To read about later changes in the status of women at U-M, see: