War Over Words

By James Tobin

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

He dared to criticize the dictionary and its editor.– Michael Adams

-

Chapter 1 A Bomb Is Thrown

Michigan, like every university, has seen plots, rebellions and ugly turf wars. Professors have schemed against chairs, chairs against deans, deans against presidents.

But there was never a bomb-throwing plot quite as violent — rhetorically speaking — as the one that Sanford Brown Meech, a lowly assistant editor of Michigan’s renowned Middle English Dictionary, waged against the dictionary’s chief editor, Thomas Knott, a distinguished professor of English.

It happened in 1938 — Depression times.

U-M was eight years into the production of an enormous dictionary of English as it was spoken in the late Middle Ages, the era of Chaucer’s rollicking Canterbury Tales.

But now money was so tight the project was close to strangling.

To keep it alive, Professor Knott, the editor-in-chief, was applying for a grant from the American Council of Learned Societies.

But Sanford Meech believed Knott, his boss, was such a disaster that he coolly tried to sabotage the older man’s bid for funding.

The following is only a spoonful of the muck that Meech hurled at Knott — while Meech was working for Knott.

Meech sent his attack on Knott to a major figure in medieval studies whose support was needed for Knott to win his grant.

Meech said he had “reached the conclusion that Mr. Knott was incompetent.”

Knott’s definitions of Middle English words were “often laughable.”

Knott’s failures as a manager “come partly from his ignorance of linguistics and partly from his lack of common sense.”

The only thing worse than Knott’s incompetence, Meech said, was “his lack of scholarly conscience. He cares nothing for scholarly accuracy or depth.”

No surprise here: Sanford Meech was soon packing his bags and leaving Ann Arbor.

But that is hardly the whole story.

He cares nothing for scholarly accuracy or depth.

– Sanford Brown Meech, regarding Thomas Knott -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

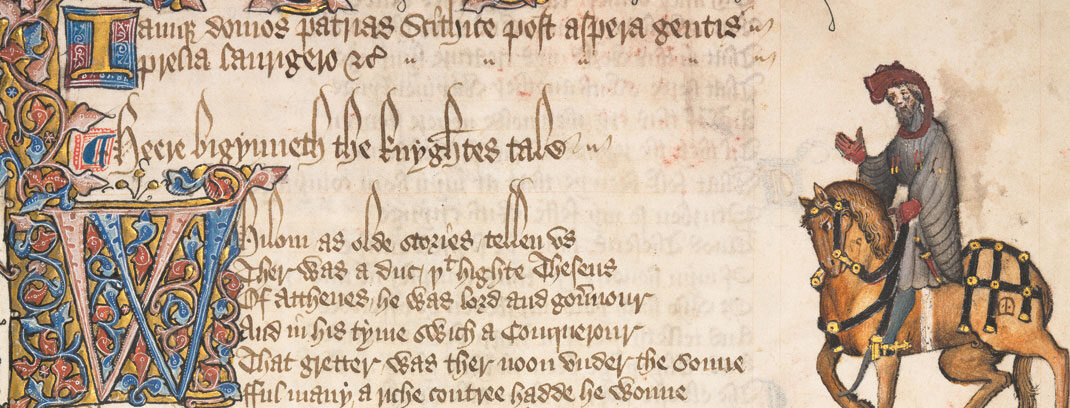

A fragment from the first column of the first page of the “A” section in Vol. 1 of the Middle English Dictionary, including the Middle English usage of “A” to mean “river or stream.”Chapter 2 Words Out of Time

Some readers are now undoubtedly thinking of this old saw: “Academic politics are so vicious precisely because the stakes are so low.”

After all, what stakes could be lower than defining some word that nobody has used in six or seven centuries — a word like “a,” to take the first word of Volume One of the MED, which in the early 1400s meant “river” or “stream”?

How could Sanford Meech possibly get so worked up about something that trivial? Especially in the middle of a depression?

But only someone outside the academic battleground, with no knowledge of what such a fight is really about, would ask a question like that.

On the inside — that is, from the point of view of someone like Meech — the stakes seemed very high indeed. To him and others — not many, perhaps, but their zeal was mighty — the Middle English Dictionary could be a portal to a lost civilization. And for that, wouldn’t it be wrong not to make a heroic sacrifice?

To see why Meech did what he did, and to learn why he is now seen as the unsung hero of one of Michigan’s greatest scholarly achievements, requires the telling of this tale.

On the inside, the stakes seemed very high.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The Oxford English Dictionary began to see publication in 1884, when its first short section, or “fascicle,” appeared, covering “A” to “Ant.” The final volume appeared in 1928, when the work’s official title was A New English Dictionary. The OED’s second edition was published in 1989 in 20 volumes. The OED Online was inaugurated in 2000.Chapter 3 The Everest of Dictionaries

The Middle English Dictionary was the offspring of a “literary Everest” — the Oxford English Dictionary.

It had been built by three generations of expert lexicographers and 2,000 volunteers who contributed five million quotations showing the proper use of more than a quarter-million English words plus their variations — 414,825 words in all.

It was 15,490 pages long, in 10 volumes.

The work had begun in England before the American Civil War. It ended the year after Babe Ruth hit 60 home runs — 70 years.

All those years and pages and words — yet the OED was not really complete.

Its subject was modern English roughly since Shakespeare. But English was much older than that. The OED pointed out antecedents of modern English words, but not in the detail needed to understand earlier versions of the language in full.

It explained each word’s development over generations — but not all the way back to the word’s origins.

Sir William Craigie, the first edition’s final editor, said the OED’s purpose would not really be fulfilled until every age of English had its own comprehensive dictionary. There should be dictionaries of Old English (pre-1100), Middle English (1175-1500); and Early Modern English (1500-1675), not to mention Older Scottish, Newer Scottish and American English.

So as the OED neared completion in the 1920s, lexicographers on both sides of the Atlantic took a deep breath and said, All right, let’s get going.

The Oxford English Dictionary, 70 years in the making, was done — but not complete.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Historical dictionaries depend on large numbers of volunteer readers who record examples of how a particular word has been used. Here, a tiny fraction of the MED’s three million citation slips includes a quotation from the poetry of John Audelay, a priest of the early 1400s — one of the citations the MED used to exemplify uses of the Middle English word for “friend.” All three million citation slips occupy their own collection at U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.Chapter 4 Epicenter of Words

In the United States, Ann Arbor became the epicenter of English lexicography.

First, in 1928, the University landed the Early Modern English project (EMED), thanks to Charles Fries, a Michigan lexicographer who had the high regard of OED’s chieftains.

Then in 1930 came the Middle English project (MED). It had begun at Cornell but funds there ran out. In Ann Arbor, sponsors figured, the two projects could share resources. So separate offices were set up on Angell Hall’s fifth floor, three stories above freshmen struggling through Chaucer and Shakespeare.

Countless boxes began to arrive in the mail from England. Each held a thick stack of plain paper slips. On each slip, one of the OED’s army of volunteer readers had copied a quotation — an example of how a single Middle English word had been used in some medieval book or poem or document.

This was the start of the MED’s raw material.

The staff would sort the slips word by word, A through Z, then check the slips for accuracy against the original sources — a job that by itself would take years.

Then more slips would be solicited from a new battalion of volunteer readers using more works in Middle English.

Then, for each word, the staff would pore over the slips and make judgments about the word’s definition, spelling, pronunciation, variations, and most important, its history.

The man put in charge was Samuel Moore, a professor of English who looked like a lexicographer from a folktale. He was small and bespectacled with an intent, peering gaze. He could be hard on students who didn’t share his love of words, a friend conceded, but “no genuine student of language ever failed to find in him a sympathetic, enthusiastic, inspiring master and staunch, devoted friend.”

Moore’s vision was not “radically ambitious,” according to Michael Adams of Indiana University, an expert in lexicography and its history who was trained in Michigan’s English Department.

Rather, Moore saw the MED as a straightforward supplement, following OED methods and organization.

But he faced one terrible complication that OED editors hadn’t.

Modern English, the language of the OED, has its variations, of course, depending on where and by whom it’s spoken. But it’s still a single, unitary language.

Middle English was different. It was a dense stew of related dialects. In the 1300s, two friars — one from the South, one from the North — could probably hold a chat, but it wouldn’t be easy.

And no one knew which Middle English dialect had been spoken where — or how a dictionary should handle the differences.

Moore, needing expert help to solve these problems, hired only the best talent, and the best of all the candidates was apparently Sanford Brown Meech.

So Meech was named one of Moore’s three assistant editors at just 27, his doctoral diploma from Yale barely dry.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Professor Samuel Moore.

In the 1300s, two friars — one from the South of England, one from the North — could probably hold a chat, but it wouldn’t be easy.

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Sanford Meech arrived in Ann Arbor with an air of arrogance in 1930, fresh out of the Ph.D. program in English at Yale.Image: Courtesy of Syracuse University Special Collections Research Center.Chapter 5 “An Uncommonly Learned Young Man”

Meech was the only child of New England bluebloods. His mother was descended from Mayflower Pilgrims. His doctoral supervisor had recommended him to Michigan as “an uncommonly learned young man. I do not recall any other graduate student in English here who has reached out more widely for information, and has shown a sounder scholarly equipment in interpreting it.”

His new colleagues in Angell Hall noticed a certain Ivy League hauteur about Meech, and yes, he wore his Phi Beta Kappa key to work. But a little arrogance could be overlooked in a man so clearly competent and hard-working.

Professor Moore sent Meech searching for words in especially important and difficult Middle English writings. (One of these was “Hali Meidhad” — “Holy Maidenhood” — a sermon on virginity aimed at the religious recluses called anchoresses, whom Meech would encounter again.)

And Moore sent Meech to England to study the vexing problem of Middle English dialects. He motored and trudged through cities and rural shires all one summer.

The work piled up. By 1934 the staff amassed 280,000 new quotations from 66,000 pages of Middle English text.

Then, at the age of 56, Professor Moore suddenly died.

In Angell Hall, Meech's new colleagues noticed that he wore his Phi Beta Kappa key to work.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Professor Thomas Knott came to Michigan after serving as editor of Webster’s New International Dictionary, an apparently impressive credential. But that experience left him ill-suited to develop the MED.Chapter 6 “A Vast Secret”

U-M’s Advisory Committee on Dictionaries replaced Moore quickly. They simply returned to the man who had been their first choice to lead the MED in 1930 — Thomas Knott of the University of Iowa, who held a Ph.D. from the elite University of Chicago.

Knott had co-written (with Moore) a standard work on Old English, and he was co-editor of Webster’s New International Dictionary, 2nd edition, the largest general dictionary of its day. He had said no to Michigan’s earlier offer only because he’d been in the middle of the Webster’s project.

Now he said yes. His credentials seemed impeccable.

But “Webster’s Second,” as Knott’s dictionary was known, was a commercial book for general readers. It sold well. But it was not a book such as the MED was meant to be — a deep, dense dictionary for scholarly specialists.

In fact, the two dictionaries were about as similar as a great physicist’s magnum opus on quantum mechanics and the “Physics” entry in the World Book encyclopedia.

Sanford Meech said Knott’s appointment was “welcome news.”

Then the MED staff got a letter from Knott that was nothing if not honest.

“I shall tell you a vast secret,” Knott told them. “I don’t yet know much about the editing of the Middle English Dictionary…”

Meech would soon think even that modest admission overstated Knott’s ability, and others at Michigan would be forced to agree.

But first, Meech’s reputation was in for its own radical change — for better and worse — thanks to his collision with a remarkable woman.

“I don’t yet know much about the editing of the Middle English Dictionary…”

– Professor Thomas Knott -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Hope Emily Allen was one of her generation’s leading experts on Medieval England. But the faculties of major research universities were closed to women, so she became an independent historian.Chapter 7 “She Seemed to Soar Above Us…”

When Hope Emily Allen met Sanford Meech in 1931, she was 48. Before she was born, her parents had belonged to a utopian Christian commune in Oneida, New York, whose unorthodox rules about matrimony and sex were enforced by a community council, with strong roles for women approved. Their radicalism steered Hope toward an unorthodox life of her own.

She grew up bookish and so sickly that for a time she was expected to die. She recovered and became a brilliant student at Bryn Mawr, Radcliffe, and Cambridge University. But tenure-track careers at major universities were closed to women in her era.

Undaunted, she made herself an independent medieval historian. By the 1920s she was a recognized expert. Thanks to a modest private income, she could steer her own course.

She scorned the conventional path toward marriage, choosing to live in close association with like-minded women who admired the advice of Bryn Mawr’s feminist president, Carey Thomas: “Only our failures marry.” (Some report that Thomas actually said: “Our failures only marry,” but either way, her take on matrimony was a bracing departure from Seven Sisters’ norms.)

When the Depression pinched her income, Allen accepted a post as assistant editor of the Early Modern English Dictionary at Michigan. She worked down the hall from Sanford Meech, whom she came to know and respect.

“Miss Allen came to our 4:30 tea breaks from time to time,” recalled Frederic Cassidy, a lexicographer who worked for the MED as a graduate student and went on to edit the massive Dictionary of American Regional English. “I remember her as a vivacious person altogether given to the scholarship in hand, pleasant with our staff and with students generally…but always seeming to soar above us, as she had every right to do.

“She came and went her intense, birdlike way, moving quickly, lightly, with piping voice and eager questions.”

Early in her career, Allen had begun to study the anchoresses whom Meech had encountered in the essay “Holy Maidenhood.” They lived celibate lives of devotion governed by a guidebook called the Ancrene Wisse. In some ways Allen’s life mirrored theirs, and she became an expert on their guidebook.

In 1934, that expertise of hers led to the most important moment in her career.

She came and went her intense, birdlike way, moving quickly...

– Frederic Cassidy -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

A fragment from an illuminated manuscript of The Book of Margery Kempe, which Hope Emily Allen identified in the 1930s as the work of a Christian mystic of the 1400s. The book is now seen as probably the first autobiography written in the English language, and one of the few records of women’s lives in the Middle Ages.Chapter 8 “A Right Wicked Woman”

It happened when Allen was called to London to inspect a mysterious volume owned by a wealthy landowner, Col. William Butler-Bowdon. It had been in his family “since time immemorial,” he said, but lately it had turned up in a ping-pong cupboard.

Turning the pages carefully, scrutinizing Middle English words that few people in the world could decipher, Allen realized she was holding the memoir of a Christian mystic of the 1400s, a proto-feminist brewer’s wife and anti-clerical evangelist named Margery Kempe.

Margery was illiterate. She dictated her words to others, recounting her mystical visions; her pilgrimages to mainland Europe and the Holy Land; her fights with priests and archbishops; and her trial for heresy. Surviving from a time when books of any kind were exceedingly rare, The Book of Margery Kempe threw open a window into the England of the 1400s. In time it was recognized as the first autobiography written in English and one of the more important literary finds of the 20th century.

“I am informed evil of thee,” the Archbishop of York tells Margery at one point. “I heard it said that thou art a right wicked woman.”

“I also heard it said that thou art a right wicked man,” she retorts. “And if ye be as wicked as men say, ye shall never come to heaven.”

As one scholar would later say, Margery “charms any reader who likes a rebel.”

The Christian mystic Margery Kempe would "charm any reader who likes a rebel."

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Allen was admired and liked by colleagues on Michigan’s dictionary staffs — except Sanford Meech.Chapter 9 Cordial Detestation

When the news spread, Hope Allen’s star soared in the small cosmos of medieval studies. And it was obvious that Margery Kempe’s tale must be published.

Nearly all Middle English writings were handwritten. So Allen took her treasure to the Early English Text Society, which printed the works so any scholar, student or library could buy them.

Allen’s own field was history, so she planned a historical supplement to explain Kempe’s mysticism. To transcribe the memoir and explain what it showed about Middle English as a language, Allen needed a Middle-English linguist as a collaborator.

For that she settled on Sanford Meech, whose training and experience fit the bill. He delightedly accepted.

But Allen was in England and Meech was in Michigan, and they never quite nailed down who would do what. Soon, through increasingly chilly letters, they were at odds.

Allen had understood that she and Meech would be recognized as co-editors and equals — a generous gesture to Meech, her junior in years and experience. But Meech wasn’t so sure of that, and Col. Butler-Bowdon, who still owned the Book, took Meech’s side. Soon a major mess was afoot.

Before long Allen cordially detested Meech, calling him “supercilious and languid.” When she accused him of bad faith, he exploded.

“A friend says I am a good judge of character,” she wrote to him at one point, “but that I have been mistaken in you. I was mistaken in not realizing how touchy you were.”

To Meech, the problem was hers, not his.

“Miss Allen is not an easy person for the ordinary man to get on with,” he wrote to a colleague. “As I have experienced it, Miss Allen’s ideal of cooperation is that she should decide, and I should obey.”

Miss Allen’s ideal of cooperation is that she should decide, and I should obey.

– Sanford Meech -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

When the Kempe manuscript was published by the Early English Text Society and Oxford University Press in 1940, Meech won pride of place on the title page.Chapter 10 Of Bugs and Boggarts

In the end, the Margery Kempe affair turned out sourly for both of them, even as it made their names in medieval studies.

The title page of The Book of Margery Kempe wound up crediting “Professor Sanford Brown Meech” as editor while “Hope Emily Allen” is mentioned only as author of a “prefatory note.”

But Allen had already taken her revenge.

Unafraid to fight with a man, she sent Meech-damning reports of the affair to the editors of both U-M dictionaries and other authorities in the field. Meech’s superiors quickly sided with Hope Allen. They now viewed Meech as an arrogant, disloyal opportunist.

That would be remembered all too clearly when Meech’s schitte next hit the fan.

* * *

The scramble for primacy between Allen and Meech looks pretty petty, especially to anyone outside their rarefied realm of scholarship.

But to the principals, their standing in that realm mattered so much because they cared so deeply about their work.

Both had given their lives to what one of Allen’s biographers has called “speaking with the dead” — the dead of many centuries past, who lived in a mysterious time impossibly remote from the mid-20th century, yet also connected to it by a single fragile strand.

That strand was the language of English, twisted and transmuted over the centuries yet still inscribed with a code that might be broken by those who gave their lives to understanding it.

Frederic Cassidy remembered Hope Allen’s fascination with the humble Middle English word bug and “all its folkloric ramifications.” Harry Potter fans would applaud to see her skipping from one creepy variant of bug to the next —bogey and bugbear to bogle and boggart, all spirit-allies of the Devil, yet playful, too.

“She tracked down the phrase ‘to put a bug in one’s ear’…meaning to give a secret hint for one’s good,” Cassidy said, “which led in turn to the word fly, another familiar spirit, and the senses of bug and fly as spies.”

Meech had trekked all over England to find differences in ancient dialects from one shire’s old documents to the next. When the photostats of Margery Kempe’s handwritten pages reached his mailbox in Ann Arbor, he and his wife stayed up late night after night, Meech puzzling out the arcane symbols on each page, his wife transcribing the words on a typewriter.

Meech and Allen were under the same spell.

In the eyes of a man like Meech — perhaps especially a young man, still starstruck by his own ambition — the MED was a sacred trust. It must be protected against all enemies.

Only a passion like that can explain his melt-down over the idiocies he came to see in his new superior, the editor-in-chief, Professor Thomas Knott.

To a lexicographer like Meech, the MED was a sacred trust.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

An MED citation slip bears a quotation from “The Monk’s Tale” in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. The Middle English says: “…what man hath freendes thurgh Fortune,

Mishap wol maken hem enemies…” Translation: “…when a man has friends that Fortune gave, mishap but turns them enemies…”Image: Middle English Citation Slips collection, Bentley Historical Library.Chapter 11 “What Is Meant?”

Knott had barely been installed as editor of the MED when Meech’s grievances started to mount.

The work on every major dictionary is slow. But Knott’s procedures would have inspired a snail.

He once directed Meech and another editor to document the history of one variation of a single word — the verb to lie, in the sense of reclining — with Knott to decide which man’s work was better. He dragged out the process for an entire semester.

One word.

Yet, bizarrely, he also urged his aides to save time by skimping on essential details, including proofreading, no less. The staff was appalled.

Then Knott sent outside experts the first 13-page sample of the MED — covering words between “L” and “laik” — with a request for advice. He asked the experts: “Should we try to do anything about dialects? In our judgment, this would demand too much time and space and the solution of very difficult, if not insuperable problems of presentation.”

The experts were bewildered. Dialects? Of course the MED had to deal with dialects!

“This is too vast a question to be answered,” replied Howard Mumford Jones, who had just left Michigan’s English Department for Harvard’s. “What is meant?”

When Michael Adams, the historian of dictionaries, studied the MED archives many years later, he concluded Knott just was not the man for the job.

“There’s no way to describe Middle English accurately if you don’t deal with that problem,” he said. “What kind of a dictionary will you have?”

In other words, Knott’s question — “Should we try to do anything about dialects?” — suggested that he did not fully understand what Middle English was.

“Anything that was tough, Knott tried to sidestep,” Adams said. “I don’t mean to be ruthlessly mean about Knott, but I think that’s the way you have to look at it — that he just lacked the imagination to deal with the things a Middle English dictionary would necessarily confront, were it to be a dictionary that people decades later, even a century, could use to great effect.”

To be sure, Knott was in a vise. MED’s funding was being siphoned off by bigger needs. A later editor of the MED, Sherman Kuhn, told Michael Adams no one could have done better than Knott, given U-M’s terrible financial constraints in the late 1930s. Knott had no choice but to slash the MED’s original scope and publish a stripped-down dictionary for students picking through Chaucer.

Maybe so — but no such rationale could soften Meech’s rage.

Anything that was tough, Knott tried to sidestep.

– Michael Adams -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Angell Hall in the 1930s. The staffs of the MED and the Early Modern English Dictionary both worked in offices on the fifth floor.Chapter 12 Seven Sins

So, early in 1938, Meech proceeded with his professional suicide mission.

His wife had just had a baby, so he had more reason than ever to fear for his job security. But he knew the MED’s budget was being slashed, and he suspected the project was on its last legs. So at least he could bring justice down on his tormentor’s head — and maybe, in the long run, save a larger vision of the MED.

He listed Knott’s sins in a long letter to Kemp Malone of Johns Hopkins, the dean of American etymologists, who was supporting Knott’s bid for funding.

Meech told Professor Malone that Professor Knott:

— had “only the most meagre equipment in comparative linguistics, and in medieval history and archaeology

— had “no gift for linguistic analysis”

— had “little administrative capacity”

— had “never attempted any etymological work for the Dictionary himself” and was “unable to criticize such work by others”

— had wasted money by collecting reams of useless new word slips

— had approved “sample pages which teem with inconsistencies, and inaccuracies, and…misspellings,” and when these errors had been pointed out, had pronounced them “good enough”

— was preparing the dictionary “only for popular appeal and superficial show.”

With that, Meech destroyed his own standing at Michigan.

According to Meech, Knott declared that entries with "inconsistencies, inaccuracies and misspellings" were "good enough."

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Meech conceded that he had been “unwise” to unleash his verbal assault on Thomas Knott, but not that he had been wrong. He is pictured here during his years at Syracuse University, where, after leaving Michigan, he landed a post in the English Department.Image: Courtesy of Syracuse University Special Collections Research Center.Chapter 13 “Unwise on My Part…”

Professor Malone, shocked, told colleagues about Meech’s sabotage, and the news quickly got back to Ann Arbor.

“Meech is very definitely out to knife you,” a friend wrote to Thomas Knott, “and the Dict. project with you unless he can become editor.”

Meech’s superiors — Knott and Michigan’s Committee on Dictionaries — were shocked as well. In short order Meech was fired.

But that was not the end of it. To get a favorable reference from Michigan, the Committee on Dictionaries demanded that Meech withdraw his charges against Knott in writing. When he did so, committee members said his letter was insufficiently contrite and demanded a second letter.

So Meech had to grovel.

“It was unwise on my part to criticize the scholarly capacities of an older man like Professor Knott,” he wrote.

He conceded that he should have expressed himself differently.

But he never said he had been wrong.

He landed in the English Department at Syracuse University, where he enjoyed a productive career.

Meech is very definitely out to knife you.

– A friend to Thomas Knott -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The MED’s final headword — the word that begins a dictionary’s entry for all the information about a particular word — is “zucarine,” the Middle English word for potash alum that people got by burning plants. It was used to make dye and glue, to tan hides and to size paper. So “zucarine” is not just a lost word. It’s a portal to everyday industry in the Middle Ages, a clue to how the English people of that time got along. (“Zucarine” appears on p. 1166 of the MED’s X-Y-Z volume, the last in a work comprising some 15,000 pages in all.)Chapter 14 The Final Word

“Meech seems to have fit perfectly the stereotype of the self-assured, even smug, Ivy League graduate,” Michael Adams writes, “one with every advantage, once the perfect student and now self-consciously an expert.”

But here’s the more important fact, by Adams’s reckoning: “The events of 1938 were crucial to the MED‘s eventual success, and Meech played an extraordinarily important role in them, because he dared to criticize the dictionary and its editor publicly.”

Thomas Knott remained as editor until he died in 1945.

But Meech’s attack on Knott staggered his reputation. Even those who defended Knott on personal grounds privately endorsed Meech’s critique of his work.

At the end of World War II, U-M determined to remain in the dictionary business. But it was clear that Knott’s tenure had been a dead end. A new start was needed.

In 1946, Hans Kurath, a scholar of German at Brown University, was appointed as Knott’s successor. When Kurath examined MED’s records, he determined that Sanford Meech had been quite right about Knott’s ineptitude.

Kurath then set the dictionary on a rigorous new course, aiming for an even more comprehensive dictionary than Samuel Moore and Meech had hoped for.

Under Kurath (editor until 1961) and two more editors — Sherman Kuhn (1961-83); and Robert E. Lewis, (1983-2001) — Michigan lexicographers marched through the alphabet and the decades. The Early Modern English project had to be abandoned. But in the 1980s, when the Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities stepped in with major funding, the MED’s staff grew and momentum accelerated.

In 2001, the final volume was published. In all, the MED consisted of 55,000 entries in 15,000 pages. It had taken 71 years, one more year than the OED. The entire work went online in 2007, vastly extending its influence and helpfulness. It was called “the greatest achievement in Middle English scholarship in America.”

* * *

Does any of it matter?

It certainly does, says anyone who takes a moment to ponder where the common currency of all our thoughts and feelings came from.

“The language we’ve got today is still largely an extension of the language of the Middle Ages,” said Michael Adams. “So understanding the language of today demands, in part, understanding the past stages of the language.”

Then there is that matter of speaking with the dead.

The Middle English Dictionary is the comprehensive record of a teeming, talking crowd of people who lived and died seven centuries ago. The pages of the MED, in print or online, “amplify all these particular voices of the past into the present,” Adams said. “You would not otherwise hear any of those voices.”

Sources included Michael Adams, “Sanford Meech at the Middle English Dictionary,” Dictionaries, 16(1995), 151-185 (the key source on the Meech/Knott imbroglio); and “Phantom Dictionaries: The Middle English Dictionary Before Kurath,” Dictionaries 23(2002), 95-114; Dianne Williams, “Hope Emily Allen Speaks With the Dead,” Leeds Studies in English 35(2004), 137-60; Frederic G. Cassidy, “Hope Emily Allen: A Personal Reminiscence,” Dictionaries 11(1989), 149-151; John C. Hirsh, Hope Emily Allen: Medieval Scholarship and Feminism (1988); Warner G. Rice, “Thomas A. Knott, 1880-1945,” College English, 7:5 (February 1946); Simon Winchester, The Meaning of Everything: The Story of the Oxford English Dictionary (2002). The author is grateful to Dr. Michael Adams of Indiana University, who unearthed Sanford Meech’s role in saving the MED, for taking the time to answer many questions about Meech, Knott, the MED, and dictionary-making in general.

The MED, completed in 2001, had taken one year longer than the Oxford English Dictionary.