The Law School Goes Under

By James Tobin

I began to realize that the only way was ‘down.'– Gunnar Birkerts, architect

-

Chapter 1 Books in the Stairwells

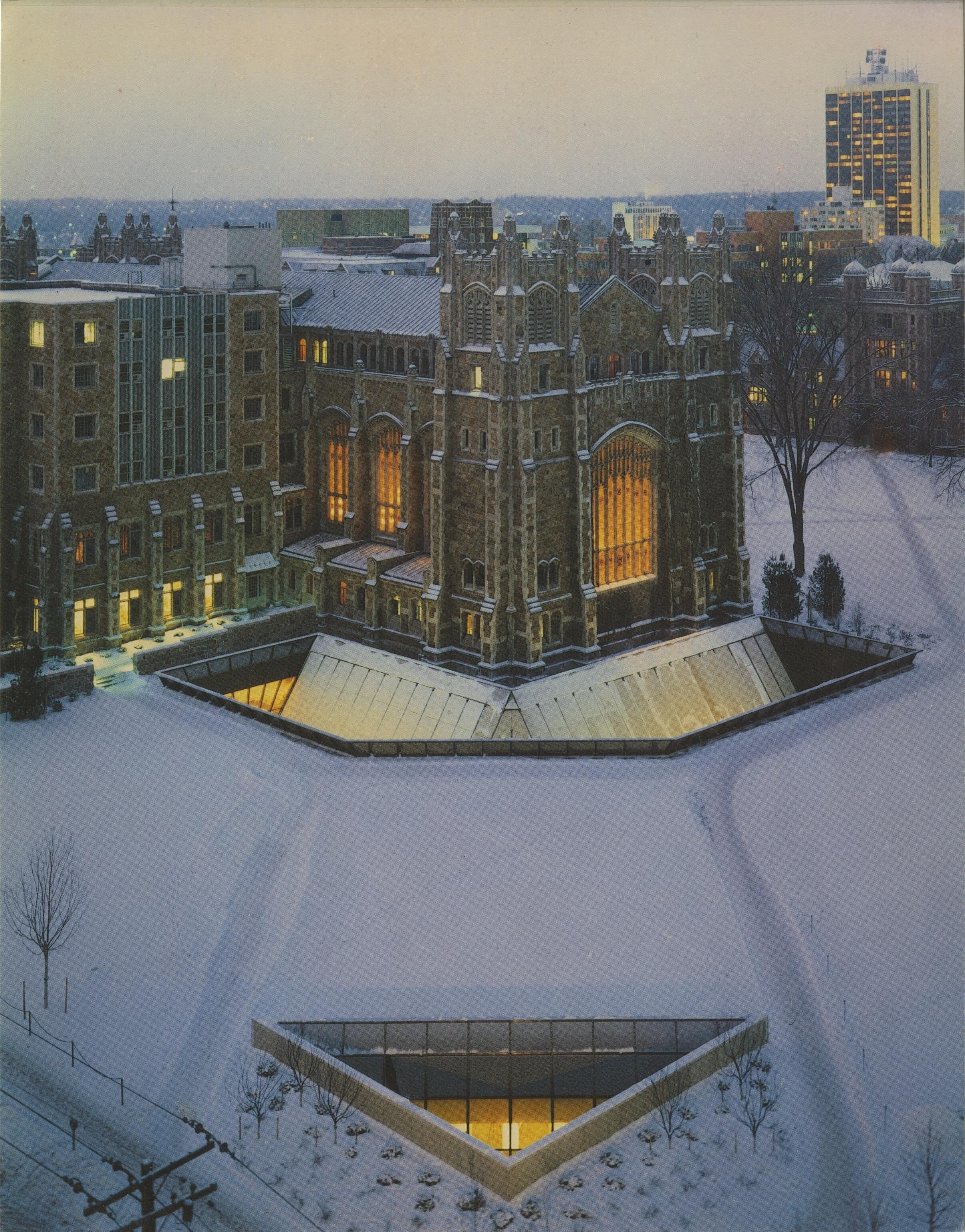

In the middle of the 20th century, the architectural crown of Michigan’s campus was the Law Quadrangle, and the jewel in that crown was the Legal Research Building, better known simply as the Law Library, a neo-Gothic mass as magnificent as a fairy-tale castle.

It had been built in the late 1920s to hold 100,000 volumes. Generations of law students had studied in the hushed cavern of its Reading Room. Many graduated with feelings for the building akin to veneration.

To alter one stained-glass window or reroute one familiar staircase would seem like sacrilege.

But by the early 1970s the library held 440,000 books – four times its capacity. By the year 2000, experts predicted, that number might reach a million.

Books were jammed in the basement. Books stood in stacks on the floor. Books were crowding the stairwells.

The Law School desperately needed a bigger library.

-

Chapter 2 The Problem of Purity

The Quad had been designed by the New York architects Edward Sawyer and Philip York, who were leading practitioners of a style called Gothic Revival. Every detail down to the medieval stone scrollwork was scrutinized by William Wilson Cook (1858-1930), the wealthy alumnus whose gifts paid for it all. Cook wanted Michigan Law to lead the nation. To attract the best faculty and brightest students, he said, the Law School must have a home of unparalleled elegance.

With England’s Oxford and Cambridge universities as models, York and Sawyer drew plans for four connected buildings in a rough rectangle — the Lawyers Club, with dining facilities and students’ rooms; the John P. Cook Dormitory, named for Cook’s father; Hutchins Hall, for classrooms and faculty offices; and the Law Library, which housed more faculty offices plus, of course, the books.

Completed in 1933, the Law Quad was praised far and wide. But its beauty brought constraints. It could not grow without disrupting the purity of the original design.

But without an addition the Law Library was going to explode.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

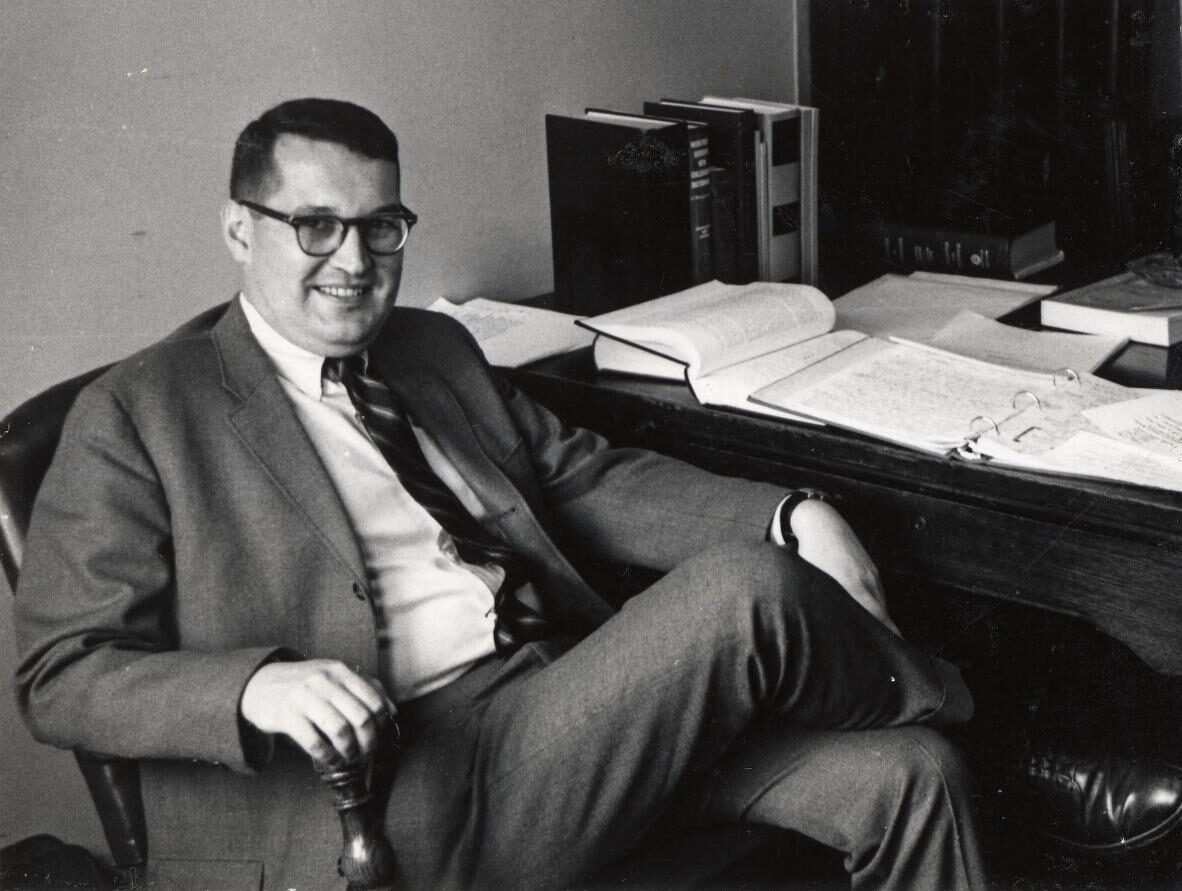

Known as "The Saint," Professor Theodore St. Antoine was tasked with solving the problem of an overcrowded legal library.Chapter 3 A “Saint,” A Superstar and A Star

The task of solving this puzzle fell to Theodore “Ted” St. Antoine, an expert in labor law known among students as “the Saint” for his attentiveness to their needs. When he was named dean in 1971, the problem of the Law Library led his agenda.

As a Law graduate of 1954 and a former editor-in-chief of the Michigan Law Review, St. Antoine was a lifer inside the Quad’s walls. But he recognized the need for change and he was open to something new.

He appointed a Building Committee of faculty and named William J. Pierce, his tough, block-shaped associate dean, as chair. “Bill Pierce gets things done,” St. Antoine would say later.

The first task of Pierce and his committee was to hire an architect.

To an architect, this was a highly prestigious job, and its difficulty only enhanced its allure. Nearly every important firm in the country made a bid.

The Building Committee put the principal partners of six firms through their paces. To each one, Pierce posed 20 exacting questions. One was: “If we pick you, are we going to have your time, or that of your associates?”

And the last question was: “If we don’t pick you, which of the other five would you recommend?”

The contenders came down to two.

One was the firm of I.M. Pei, the world-renowned architect who had designed such landmarks as the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston and the National Gallery East Building in Washington, D.C.

The other firm was led by Gunnar Birkerts, a professor of architecture at U-M. Based in Detroit, he, too, had a major reputation, though not on the level of Pei’s.

Pei submitted “a strikingly beautiful concept,” St. Antoine recalled later, “a kind of brutal cement approach.”

Birkerts’ ideas were impressive but less definite and dramatic than Pei’s.

St. Antoine was leaning toward Pei. But Pierce persuaded the dean that before deciding, they should visit buildings completed by the two architects to “kick the tires.”

The results were enlightening.

Pei’s buildings were gorgeous, but they didn’t always work. Windows were falling out of his John Hancock Tower in downtown Boston.

And the Building Committee was told they could expect to see Pei just twice – first on the day his design was approved, then on the day the ribbon was cut.

At Birkerts’ buildings, they were assured that Birkerts himself would be on hand for every sweaty stage of the process, making sure of each detail.

In Detroit, the committee looked at Birkerts’ addition to the Renaissance-Revival Detroit Institute of Arts. The addition’s exterior walls were made of reflective black granite. Beverley Pooley, law professor and director of the Law Library, said “they were so placed that whenever you looked at the new building, you saw the mirror image of the old building. In other words, his building was sort of invisible.”

An invisible building – or a “non-building,” as Pierce called it – might be just what the Quad needed.

The committee chose Birkerts.

Now the next questions came to the fore:

Where could they build an addition without spoiling the Quad?

And who would pay for it?

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Professor William Pierce.

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The venerable Law Library has been revered by alumni for generations.Image: Michigan PhotographyChapter 4 When $3 Million Isn’t Half Enough

Not the University. The Law School would have to raise the money from private sources. So St. Antoine tiptoed into the delicate process of fundraising.

University fundraisers took the dean to school. To get going, he would need big anchor gifts from foundations and the Law School’s wealthiest alumni.

St. Antoine recalled that “one of the reasons I had become a lawyer and a law teacher was to escape the sales career of my father.” He dreaded the idea of asking anyone for money, even for the best of causes. Now he had no choice.

But he had early success.

Thanks to an adroit pitch to the Dow Foundation in Midland, he scored a pledge of $1 million. Close to another million came from Jason Honigman, the tough head of Detroit-based Honigman, Miller, Schwartz and Cohn, who also owned a chain of supermarkets.

Then there was Calvin Souther, a fearsome old Law grad of the 1920s. He was from Oregon. Like Honigman, he presided over a major law firm but also had made a fortune in business. St. Antoine set out to woo him.

But an obstacle arose when a young associate from Souther’s firm arrived in Ann Arbor to vet potential law clerks. When a female law student appeared for her interview, the lawyer said: “Young lady, there really is no sense of my interviewing you. Ours is a boy-girl firm. The lawyers are the boys and the secretaries are the girls.”

When St. Antoine heard about this, he invoked the Law School’s policy – Souther’s firm was no longer welcome to recruit at Michigan unless its “all boys” policy changed.

Then the dean got on a plane to go see the old man.

In Souther’s office, St. Antoine found Souther wearing a deep scowl.

“Well, Cal,” he said, “you can probably guess why I’m here.”

“I can,” Souther rumbled.

“I’m awfully sorry, Cal,” said the dean. “I can only say I hope very much this is not going to affect your views of the University of Michigan Law School. But we do have certain standards, and we have to apply them to everybody.”

The scowl began to crack. Then Souther threw back his head and laughed.

“That young man is the dumbest lawyer I ever hired!” Souther said. “I guess this law firm eventually must move into the twentieth century. We’ll work it out.

“You don’t have to worry about your million dollars.”

* * *

Three million dollars was a good start. But St. Antoine needed $5 million more, and his alumni included only so many Jason Honigmans and Calvin Southers. He would have to raise much of the rest through smaller gifts from graduates less well-heeled.

And if the alums loved the Law School, as St. Antoine knew they did, he also knew that one thing cemented their loyalty. It was the Law Quad itself.

But any building big enough to meet the need was going to overwhelm the profile of the original Quad or at least distract from it mightily.

And if you messed with the Law Quad, you could kiss your millions goodbye.

-

Chapter 5 Moles in a Hole

Birkerts’ first design envisioned the addition across Monroe Street with a cold-weather connector. But that was quickly shot down as impractical.

Before long he was back with a new design and a model. St. Antoine thought it was a spectacular solution. But the faculty and alumni would have to agree.

A perfect occasion was at hand for a dramatic presentation – the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the Lawyers Club. It was decided that Birkerts would unveil his model at an elaborate anniversary dinner, with many faculty and important alumni in attendance.

The setting was the elegant dining hall of the Lawyers Club, one of the most beautiful rooms on the campus, with chandeliers and soaring windows. A brass quintet was brought in to play baroque music. St. Antoine and his assistants set up everything to enhance the unveiling of Birkerts’ breathtaking model.

Finally the moment arrived. The model was revealed. The attendees stared.

Running along the south side of the model Law Library they saw the representation of a stunning modern structure made of steel and glass. Several stories of the edifice rose above the level of Monroe Street and wrapped mammoth glass arms around the original Library. The bottom stories sliced deep below the surface of the ground.

Finally someone said: “Ted … what are you doing to us?”

“You’re putting us down in a hole like a bunch of moles…”

“It’s debilitating…”

“…demeaning…”

And that was just about the underground part. The modernist structure above street level drew its own howls. Next to York and Sawyer’s neo-Gothic grandeur, it would look like a structure out of “Star Trek.” Pierce called it “The Halo” and “a glass menagerie around a cathedral.”

Then they heard about the cost, which Birkerts estimated at $12 million, half again as much as the fundraising limit.

Finding $8 million was going to be hard enough. How could they possibly raise $4 million more?

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Architect Gunnar Birkerts was known for designing buildings that focused more on the interior than the exterior.Chapter 6 “It Will Not Be Dark”

In later years several individuals claimed credit for the breakthrough idea. St. Antoine was only one of them, as he readily conceded.

Early one morning as the dean was shaving, a mathematical idea occurred to him. As he recalled it years later, the thought came to him as follows:

“The estimated cost is $12 million. The estimated revenue is $8 million. We have a building that is going to be two-thirds underground and one-third above ground. And we are having an absolute revolution in the ranks with regard to that above-ground glass-and-steel portion.

“The answer is mathematically obvious. One-third of this building is causing all the problem. We’ll just cut off the top and put the whole thing underground.”

Birkerts’ thinking was moving in the same direction.

“I began to realize,” he remarked later, “that the only way was ‘down.’”

* * *

Born in the tiny, eastern European nation of Latvia in 1930 and trained in the modernist Bauhaus school of architecture, Birkerts had emigrated to Michigan in the 1950s. He found work with two eminent architects based near Detroit – first Eero Saarinen, then Minoru Yamasaki. In 1959 he formed his own firm, designing structures known more for their insides than their outsides.

He was fascinated by the uses of natural light. In his view, light was another material, like brick or stone, to be shaped and deployed in the creation of a design.

But how could anyone dig a hole three stories deep, sink a building into it, yet fill it with sunlight?

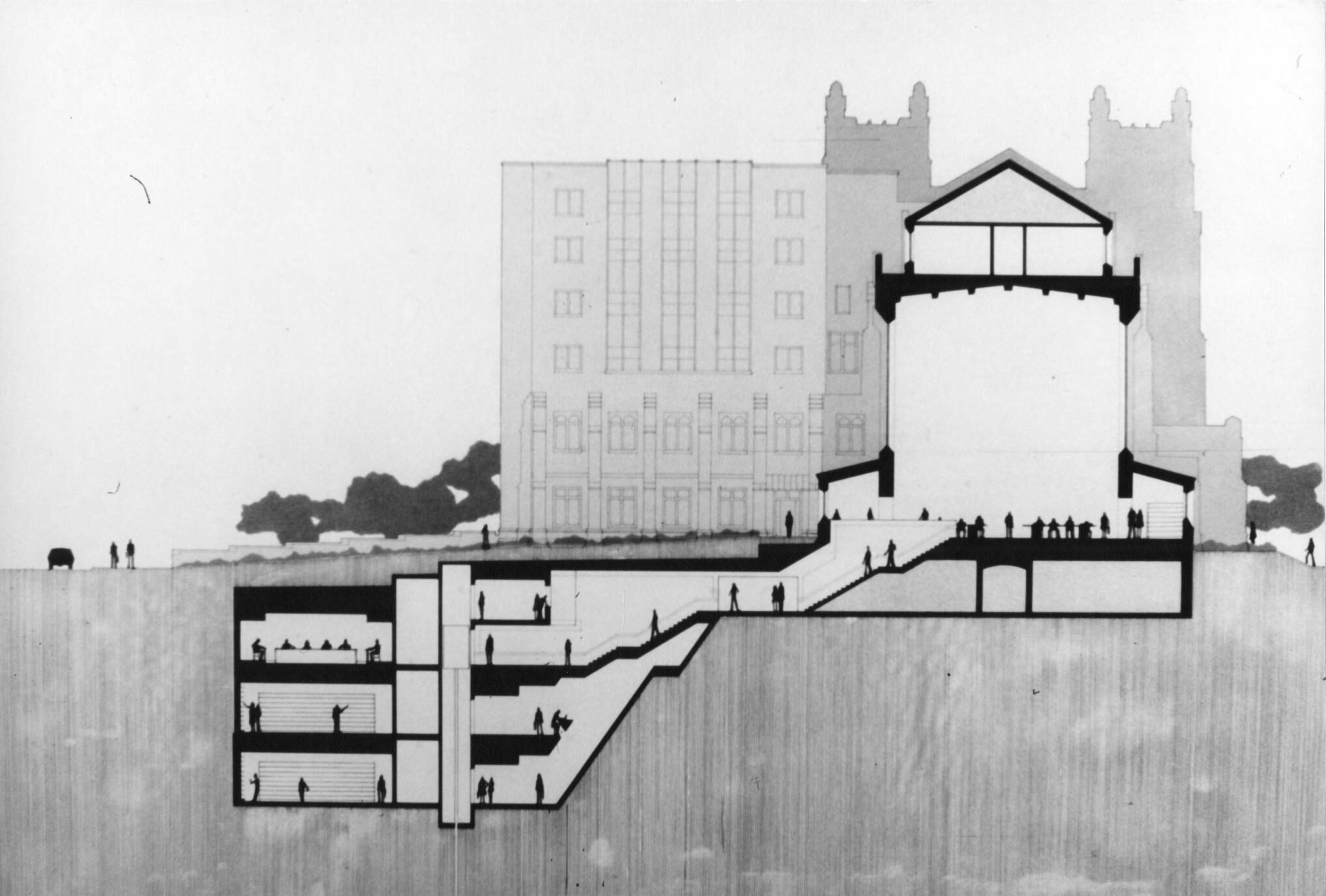

The architects studied the space at the southeast corner of the Law Quad’s block. Then, on paper, they drew a broad, backward L-shape enclosing the southeast corner of the Law Library.

They imagined the L-shape as a deep trough. In cross-section, it would form a V in the ground. One side of the V would be a sloping window-wall of glazed glass. The other would be a wall of white limestone. Leading away from the wall and the window, the designers drew spaces for library stacks, meeting rooms and study areas.

On paper, these were nothing but two-dimensional shapes. To the layperson, even the cross-sections conveyed nothing of what it would be like to stand inside the imagined spaces.

It just looked like a glorified basement.

“I do not think it is a good idea to put our entire library underground,” Beverley Pooley wrote in a memo. “It may be that this feeling of mine is purely psychological, and stems from my general distaste for living like a mole in subterranean caverns.”

Who wanted to work in the dark?

Again and again, Birkerts simply insisted: “It will not be dark.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

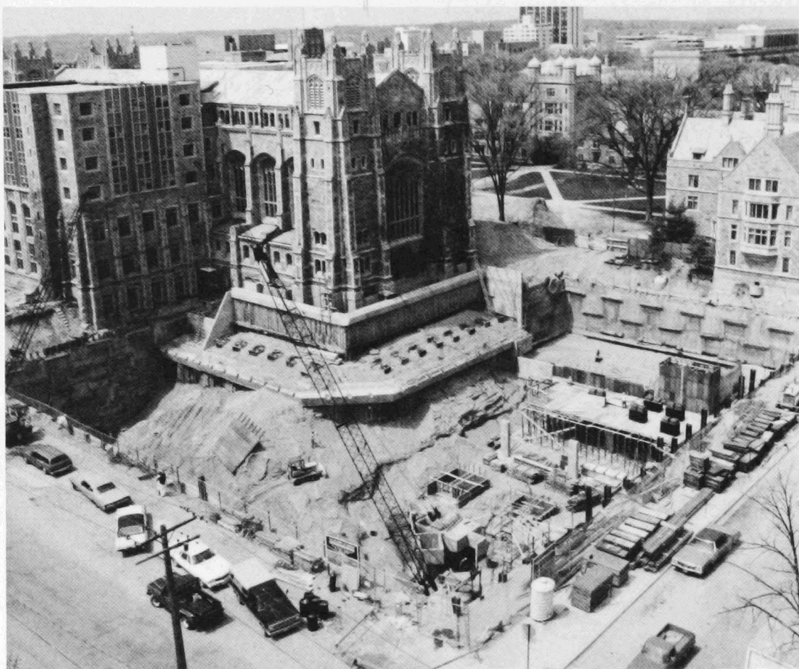

Excavation of the new library at the southeast corner of the Law Quad.Image: Quad Notes, U-M Law SchoolChapter 7 A Non-Building

There were many skeptics. But the new design gained a key supporter in Associate Dean Pierce.

As chair of the Building Committee, Pierce thought the new plan solved all problems. He called it – approvingly – a “non-building,” with nothing to spoil the profile of the original Quad. And it fully answered the needs for more space.

Others were shocked at the notion of spending millions on a hole in the ground.

The view among some, Pooley recalled, was that “it would be a terrible, botched mess … and we would be the laughingstock of the world because we had spent such a huge amount of money on a dim, unlit, horrible, sweaty building.”

Birkerts and his team created a model. It was small enough to sit on a desk. People came in to stare at it from this angle and that.

Some began to see what the architects saw. Others were utterly unpersuaded.

At one contentious meeting, a faculty member said it was ludicrous to place a huge window down in an exposed trench. What if a student pitched a big rock at it?

“Strong glass,” replied the taciturn Birkerts. “Will not break.”

What about a heavy construction sawhorse – what if students threw that down on the glass?

“Strong glass,” Birkerts repeated. “Will not break.”

In mounting exasperation, the professor asked: “Well, what if somebody drove a car down onto that glass?”

Birkerts, straight-faced, let ten seconds pass, then said: “Would break.”

Another key supporter emerged. This was Thomas Sunderland, an Ann Arbor native who had been deeply protective of the original Quad. The son of Edson Sunderland, a leading member of the law faculty from 1901 to 1956, the younger Sunderland had been a U-M undergraduate when the Quad was being designed. He became an antitrust expert and a corporate executive. When he came around to share Pierce’s appreciation of the underground design, other alumni – knowing of Sunderland’s respect for the original buildings – began to turn in Birkerts’ favor.

A few faculty members accused Pierce of selling out to the alumni. Pierce said no, it was just the best design. But in any case, he recalled later, “you’ve got to raise the money. And if you have a group [sending] fliers asking for capital gifts, and another says, ‘Don’t send the money because they are going to devastate the Quad,’ what are you going to do? You can’t have that.”

Pierce had become a lightning rod. With reluctance, Dean St. Antoine replaced him as head of the project with a milder-mannered professor.

The die was already cast. One by one the decision-makers said yes to the underground plan – the Building Committee, the Alumni Committee, the dean and finally the regents.

But the ordeal was hardly over.

Now came months and months of dirt and noise. There were cost overruns. A concrete retaining wall had to be built to make sure the Law Library would not fall into the growing hole next door. The mound of excavated gravel, rock and dirt in the middle of the Quad grew so high that students called it Mount Cook. The contractor hired to dig the hole misjudged the site’s soil conditions and went bankrupt.

And then in 1981 it was done.

"We would be the laughingstock of the world because we had spent such a huge amount of money on a dim, unlit, horrible, sweaty building."

– Professor Beverley Pooley -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

"You are looking at a proud, wonderful expression of contemporary American skill, architectural design and taste," one professor said.Chapter 8 “An Icon of the Mother Building”

People began to go down the new staircase that led from the grand old Reading Room into the strange new space underground.

Just as Birkerts had promised, it was full of sunlight.

Downward-streaming rays struck the sloping limestone wall above and bounced further downward through all three stories. A deep triangular window at the far corner of the site admitted still more light.

Then came another surprise. Looking up, people found themselves viewing the towers and spires of York and Sawyer’s original library from a fantastical point of view. It now loomed far higher than it did at ground level. The effect was to make it seem suddenly twice as tall and spectacular as ever.

As Birkerts said: “It makes a sort of icon of the mother building.”

That was not all. In the great window-walls of the V-trough, the architects had placed mirrored mullions to refract the light and scramble the images from above. From certain points below it was like looking up into a giant kaleidoscope.

Put another way, the mirrors sent fragmented images of the old neo-Gothic stone down into the new space. It was a kind of visual bridge uniting the old and the new.

And even at the very bottom, 54 feet below the turf, there was natural light – a lot of it.

The verdict was not unanimous. Some did not care for the way the entrance to the staircase down to the addition jutted into the old Reading Room.

But no one could deny that Birkerts had conjured a kind of miracle.

The Journal of the American Institute of Architects would declare that Birkerts & Associates had designed “probably the most esthetically satisfying large underground building to have penetrated American soil.”

In an interview conducted years after the construction was complete, Beverley Pooley remarked: “It just shows our incapacity to visualize these things, and the greatness of Birkerts as an architect. I hope that we helped a little, but we – I’m speaking for myself – I do not think we had any idea.

“Even those of us who had all the time been very impressed with Birkerts and what he could do were absolutely astounded at the loveliness of this building.”

An Englishman by birth, Pooley pointed out that William Cook’s original Law Quad, however lovely, was an imitation of European forms. Birkerts, he said, had created something entirely original and American.

“When you’re looking at the architectural beauty of the Law Quad,” he said, “you are looking … at derivative art. The people who built this said, ‘We do not have anything [architectural] that we think is worthwhile, so we’re going to copy something from England three or four centuries ago.’

“When you go down there [into Birkerts’s addition], you are looking at a proud, wonderful expression of contemporary American skill, architectural design and taste. And to me that is slightly more authentic.”

* * *

The addition was named for Allan F. Smith and his wife, Alene. Smith was a universally popular professor and dean of the Law School (1960-65); then the University’s vice president for academic affairs (1965-74); and interim president in 1979.

In 2018, the Library held 730,461 printed volumes.

Key sources included the papers of Gunnar Birkerts & Associates and oral histories conducted with three key players in the construction of the Law Library addition — Theodore St. Antoine, William Pierce and Beverley Pooley. All these materials are housed at U-M’s Bentley Historical Library. The writer thanks Margaret Leary, biographer of William W. Cook and director emerita of the Law Library, for her advice and help.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The library addition and its green space.Image: Michigan Photography -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Natural light fills the library, as promised by architect Gunnar Birkerts.Image: Michigan Photography

-