Professor Porta’s Predictions

By Kim Clarke

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

It will be a gigantic explosion of flaming gases, leaping hundreds of thousands of miles into space.– Albert F. Porta

-

Chapter 1 “The most terrific cataclysm”

In Chickasha, Okla., a week before Christmas of 1919, a young girl slipped on a new dress. If she was going to meet her maker, she wanted to look special.

Across the Atlantic, the poor of Paris gathered in churchyards to say prayers. They, too, were preparing themselves.

On Canada’s Vancouver Island and in Oshkosh, Wis., people drank and danced, content to wind down their lives in glorious, boozy parties.

It was Dec. 17, 1919, and the world was all but coming to an end. From England and France to Cleveland and Indianapolis, people huddled, prayed, cried and stared into the sky, waiting and watching for a dramatic climax. There would be torrential rains, massive lava eruptions and deafening winds that would rattle the earth for days.

It would be, predicted Professor Albert F. Porta, “the most terrific weather cataclysm experienced since human history began.” And the United States would be the epicenter.

As newspaper readers across the country knew, Albert F. Porta was a noted forecaster. His calculations were grounded in science. And his name was attached to a very distinguished place: The University of Michigan.

And so people braced for the end.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Albert Porta's 1919 prophesy had people on edge throughout the world.Image: The Times Dispatch, Richmond, Va.

-

-

Chapter 2 A Jesuit Engineer

Albert Porta was born Alberto Francisco Porta in 1853 in Italy’s Piedmont region, and later studied at the University of Turin, where he learned architecture and civil engineering. That expertise – and connections with the Society of Jesus – eventually took him to Central America after Jesuit leaders called upon him to help rebuild and reinforce churches and bridges damaged by earthquakes.

Porta, his wife Angelina and their five young children moved in 1894 to Quetzaltenango, Guatemala. After nine years’ work by Alberto, and the addition of two more children to the family, the Portas emigrated to the United States and a new home in the San Francisco Bay Area.

By 1907, Albert Porta was a professor of civil engineering at Santa Clara College, a small, all-male Jesuit school, where he taught mechanical drawing, civil engineering, architecture and geometry.

For all his knowledge, and whether as a student or teacher, at no time did Albert Porta pursue the disciplines of astronomy or meteorology.

But it was at Santa Clara College where he discovered the campus observatory and scholars trained to explore the heavens and predict the weather. Professor Porta’s career was headed in a new, bizarre direction that ultimately would taint the reputation of a much larger university in Ann Arbor.

-

Chapter 3 ‘Padre of the Rains’

It was 1913 and Porta, for reasons unknown, was no longer a faculty member. But the leaders of the Santa Clara observatory hired him for his mathematical skills, specifically to determine electromagnetic connections between sunspots and planets of the solar system.

Porta’s supervisor was the Rev. Jerome Sixtus Ricard, director of the observatory and a professor highly regarded for his knowledge of the weather. He was “Padre of the Rains,” and believed sunspots – gaseous flares erupting from the surface of the sun – shaped the Earth’s climate. His monthly publication, The Sunspot, was a sort of weather bible for those along the Pacific coast. His forecasts were remarkably accurate.

Father Ricard thought Porta perfect for the task: He could busy himself computing the “all-absorbing calculations” needed to determine precisely where flares would originate on the sun’s surface, thus advancing the science of forecasting.

“Hence the need of a man, who, having nothing else to do, can put his whole mind on a given question and keep it there,” the priest wrote, “well knowing that his bread and butter are safe in the meantime.”

It was a temporary hire that Ricard would deeply regret.

Porta took what small knowledge he gained at the observatory and, after two years, left to establish his own weather and earthquake forecasting service. He claimed new methods for predicting earthquakes in an anxious region still recovering from the 1906 quake that devastated San Francisco. And he invoked Ricard’s name to bolster his reputation while simultaneously questioning the scientific veracity of the Santa Clara observatory’s work.

Ricard was furious.

“[Porta] has been only a sort of obtruding habitué, making frequent visits and putting a lot of questions in reference to the astronomy of the sun, the planets, weather and earthquakes,” Ricard told Sunspot readers. “… his forecasts are not only not inspired by us but may be just the opposite of what we would say, even on the hypothesis, as is pretended, that he has learned all our ideas and ways correctly.

“Forecasting is not simply a matter of abstract principle, but above all, one of long experience, and such an experience too, as is founded on the records of natural facts, showing how to apply principle to a concrete case. Professor Porta is not, therefore, in any sense, a duplicate of the Observatory of the University of Santa Clara.”

Porta knew nothing about astronomy before coming to the observatory, the priest wrote, and any meteorological terminology he used was the spouting of “a humble parrot.”

Ricard also blasted Porta for owning no scientific equipment, not even a telescope. “Without instruments of observation, one is no more able to launch, intelligently and trustworthily, even a mere general weather forecast for the guidance of people on sea or land or air, than a log can fly.”

It should be noted that Ricard was regularly featured in area newspapers, with forecasts that carried far less ominous tones. Professional jealousy may have fueled his criticisms. But none of the priest’s protestations mattered. Porta’s weather predictions were now being printed in the San Jose newspaper, and soon would spread to newspapers across the country.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Newspapers carried detailed sketches and doomsday headlines about Porta's predictions.Image: The Washington TimesChapter 4 ‘Storms, eruptions and earthquakes’

By 1919, the byline of Professor Porta – “noted scientist, savant and archaeologist” – filled columns of newsprint. And newsprint was the coin of the realm for mass communication in the early 20th century.

In 1918, there were more than 22,800 newspapers – dailies, weeklies, monthlies – circulating in the country. (A century later, that number is about 8,400.) At the time of Porta’s forecasts, residents of America’s big cities had their choice of papers competing for readers. In San Francisco, there were some 20 dailies, including several in Chinese, Italian, Japanese and German. Chicagoans could pick up the Tribune, Examiner, News or Herald, as well as papers in Polish, Yiddish, Slovenian and Lithuanian that catered to the city’s ethnic neighborhoods. Readers in Philadelphia paged through the Bulletin, Record, Inquirer, the North American and its rival Public Ledger.

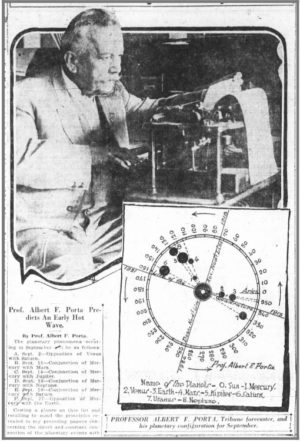

Albert Porta’s home newspaper was the Oakland Tribune, which syndicated the prognostications originating from his self-designated Instituto delle Scienze Planetarie – the Institute of Planetary Sciences. Every month, Porta delivered a weather report for the entire country, region by region.

Just as Ricard had charged, Porta used no scientific apparatus. Rather, he relied upon a federal government booklet called the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac, which annually published the movements of the earth, sun, moon and stars.

“This shows the daily positions of the heavenly bodies and their rate of motion,” Porta told Tribune readers. “I do not use a telescope; I have no need of one; I need only paper and pencil and time to figure.”

Bad weather, he believed, was caused by sunspots, and sunspots were the result of electromagnetic waves generated when the sun aligned with one or more neighboring planets. The more planets in direct line with the sun, the bigger the sunspots and resulting storms on Earth: earthquakes, geysers of lava, hailstorms, tornadoes, lightning and flooding.

So when Porta consulted the American Ephemeris, what he saw for December 1919 was ominous. Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn and Neptune would align on one side of the sun, and on the opposite side lay Uranus. This septet, which he christened the League of Planets, would create a spear of energy that would effectively puncture the sun.

“The sunspot that will appear December 17, 1919, will be a vast wound in the side of the sun. It will be a gigantic explosion of flaming gases, leaping hundreds of thousands of miles into space. It will have a crater large enough to engulf the earth much as Vesuvius might engulf a football.”

Porta began alerting readers in the summer of 1919 to this pending meteorological doom. Newspapers in Sheboygan, Wis.; Geneva, Ala.; Richmond, Ind.; Abbeville, La. – they all carried his warnings. “The whole solar system will be strangely out of balance. What will be the outcome? My knowledge does not permit me to state beyond the fact that the storms, eruptions and earthquakes will be tremendous in their strength and scope.

“Remember the date – December 17 to 20, and after.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Professor Porta found fame through the Oakland Tribune and its syndicating of his forecasts.Image: The Oakland Tribune

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

William Hussey spent 14 years in California as an astronomer and professor before returning to U-M.Chapter 5 ‘A scientist or a fakir?’

When a meteor ripped through the skies of southwestern Michigan in late November, anxious residents were certain it was an omen: Albert Porta was right about terrible storms coming in December.

“All bosh,” said William J. Hussey. Professor Porta, he said, was a fraud.

A professor of astronomy at the University of Michigan, Hussey was in his second decade as director of the Detroit Observatory. After graduating from U-M and before returning to join the faculty, he worked in the same region as Porta as an astronomer at Stanford University and at the University of California’s Lick Observatory. He had serious academic credentials and awards, and viewed Porta’s theories as absurd.

The alignment of planets presented no threat to Earth’s atmosphere. “It is a perfectly natural occurrence, and should not be regarded with any fear or credulence,” Hussey told reporters. “The scare is of the type the people of the dark ages were frightened with every few weeks, but has no place in an enlightened world like that of today.”

He added: “If the stars and planets were extinguished, our eyes would miss them, that is all.”

Hussey was already receiving letters from concerned citizens questioning the Dec. 17 predictions. (“Is this Prof. Porta a recognized scientist of standing or a fakir?” wrote a school superintendent.) To every writer, Hussey provided calm assurance that all would be well. “I do not know anything about Professor Porta, who he is, where he lives, or what his training has been. His prediction merits no consideration whatever.”

Hussey told the media the same. And in an ironic twist, it was his vehement rebuttals that may have led to Porta becoming associated with U-M in the first place.

Prior to the late November meteor reports, Porta’s name was never connected to the University of Michigan. It was only after newspaper accounts carrying Hussey’s dismissals, and his position at Ann Arbor, that Porta somehow was lumped into the U-M faculty. It was perhaps the error of a copy editor merging stories, or a rewrite man up against a deadline at a wire service. No matter. Newspapers around the globe now routinely published dire, end-of-the-world forecasts attributed to “Professor Porta of the University of Michigan.”

These were not small articles. Half and full-page features detailed the pending cataclysm, with sketches of the solar system and photos of an intent Porta focused on a typewriter and the forecasts poring forth.

In mid-December, the New York Times published a full-page photograph of the sun, newly captured by the esteemed Mount Wilson Observatory in California. Distinct sunspots, the paper noted, “draws added interest just now from the evidently groundless but apparently serious alarm which has swept over parts of the country over predictions, attributed to Professor Albert Porta of the University of Michigan, that the earth may be visited between Wednesday and Friday of this week with the worst electrical and weather catastrophe in history …”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The Michigan Daily used its front page to dismiss any ties between U-M and Albert Porta.Chapter 6 ‘He has never been here’

U-M President Harry B. Hutchins was surely exasperated. The leader of the University since 1910, he had seen the campus through the dual calamities of world war and an influenza pandemic, with each claiming the lives of Michigan students. He was ready to step down, and twice had resigned – in private – in letters to the Board of Regents. His retirement was now finally public and pending, and he was busily lobbying the leader of the University of Minnesota, Marion L. Burton, to take the U-M presidency.

But what of this Professor Porta?

“To the best of my knowledge he has never been here,” Hutchins told The Michigan Daily and any other newspaper that inquired.

The Daily was the first news outlet to question Porta’s qualifications and seemed incredulous that he was being associated with U-M. “Whoever started the rumor that ‘Professor’ Porta, who has startled the world with his statements that the world is coming to an end Dec. 17, is from the University of Michigan, had Bolshevik ideas probably.”

The Astronomy Department also distanced itself from a scholar it never employed. “I never heard of him in a professional way and if he is a student of astronomy I would know him,” an unnamed professor – perhaps Hussey – told United Press International on the eve of supposed destruction. “The theory is absurd as a basis for prediction.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The work of cartoonist John McCutcheon led the front page of the Chicago Tribune when Porta's forecast fizzled.Image: The Chicago TribuneChapter 7 ‘World Wags On’

And then came Dec. 17.

Residents of Reno, Nev., awoke to a screaming headline:

AMERICANS WAIT IN VAIN FOR CATACLYSM THAT IS TO BREAK UP THE UNIVERSE

The National Weather Bureau in Washington, D.C., fielded phone calls and telegrams. Men working in Oklahoma’s zinc and lead mines refused to go underground for fear of being buried alive. In Ohio, Charles Johnson left his farm to travel 60 miles into Cleveland, where he purchased a seat to watch the world end only to learn he’d been swindled out of $15. “They told me all the members of my religious faith were to wait for the end in Cleveland.”

And in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., Samuel Heaslip prepared to bury his 54-year-old wife, Anna. She killed herself the day before, unable to face the end of the world.

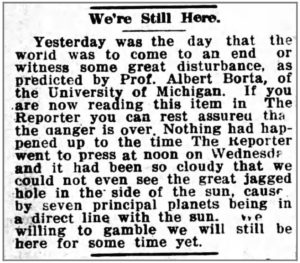

However tragic and frightening the day was for some, many more people scoffed at the Porta prediction and went about their lives amidst typical weather conditions.

In Ann Arbor, engineering students held an impromptu party at the Michigan Union. “To be sure, the idea of the world coming to an end has its advantages,” mused the Daily. “Why study? That was the word on every tongue last night. Prayer and fasting did not seem to appeal to the popular fancy as it did a few centuries ago when the planets lined up on company front. However, a pronounced run of the movies was reported.”

By the afternoon and into the next day, hundreds of papers wrote, many with tongue firmly in cheek, about the earth continuing to spin.

Another Fool Prophesy Fails; World Wags On

End Of World Is Postponed

Well, Well! Mother Earth Keeps On The Same Old Way Today

Fake! Bum Show! World is Intact!

The Oakland Tribune, originator of Porta’s weather reports, covered the non-event with tremendous understatement. “From one end of the earth to the other went the word of Professor Porta’s predictions, but in the going they were badly garbled.” (Months earlier, the same paper had teased readers with “the most important prediction” of “Earth reeling under the blows of sunspot magnetism.”)

U-M continued to issue its denials of Porta, and was mocked for distancing itself from a forecast by a charlatan it had never employed.

And Professor Porta himself? He remained confident in his abilities if not unsettled that his forecast had been “twisted and distorted by some unscrupulous people.”

More important, he warned that earthquakes and storms remained on the horizon. Particularly nasty weather along the Pacific coast would “establish an altogether new record for ferocity and destructiveness.” The worst, he said, would come on Christmas Day.

“My critics have done me a severe injustice in distorting my prognostications. But when the events themselves have proved that I was correct, I will rise like a lion and show them I know whereof I speak.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The headline said it all for Iowa readers on Dec. 19, 1919.Image: The Leon Journal-Reporter

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

A massive coronal hole - 50 times the size of Earth - as it appeared on the bottom of the sun in January 2014.Chapter 8 Sunset

While William Hussey protested Porta’s work in the media and in letters, the doomsday forecast did not merit mention in the diary he kept. The U-M astronomy program, long considered one of the country’s best, continued to thrive and suffered no lasting harm from its association with Porta. Under Hussey’s leadership, astronomy courses had 15 times as many students enrolled as when he began teaching 20 years earlier.

Hussey died in 1926 while making his way to South Africa to oversee construction of U-M’s first observatory in the Southern Hemisphere. It opened two years later as the Lamont-Hussey Observatory.

Professor Porta’s byline continued to appear in newspapers, but in far fewer than before his apocalyptic forecast. Within two years, only the Oakland Tribune was carrying his forecasts. He died on a spring day in 1923, at age 70, with the weather fair and warm.

Sources: Contemporary news accounts; “Scientific Pilfering,” by J.S. Ricard, The Sunspot; Hussey Family papers, Bentley Historical Library; Harry Burns Hutchins papers, Bentley Historical Library; N.W. Ayer & Son’s American newspaper annual and directory; Albert Porta naturalization petition.