No Admittance

By Kim Clarke

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

This University has been organized and established for the education of young men ... to adapt it to the education of both sexes would require a complete revolution.– Regent Donald McIntyre

-

Chapter 1 Seeking Entry

Sarah Burger was 21 years old when she prepared a letter to send to the men running the University of Michigan.

It was the winter of 1858. She was single and lived in Ann Arbor with her parents; her father was a dentist and her mother a homemaker. Together, they would have watched as the University had evolved through the years, with a new observatory pointing its telescope toward the heavens and a stunning chemistry laboratory for the ever-growing number of students interested in science.

Sarah believed there needed to be yet more change on campus and said as much in her March letter to the Board of Regents. In three months, she wrote, she intended to enroll at the University of Michigan. And, she added, she would be bringing another 11 women with her.

Burger’s actual letter has been lost to time. Regardless of its precise contents, however, her missive caused a small convulsion at the board table. The University of Michigan, after all, was an institution that had always been operated by, and for, men.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Sarah Burger.

-

-

Chapter 2 “An Intellectual Male Club”

The U-M campus of 1858 was very, very male.

The University had been operating in Ann Arbor for 17 years since moving from Detroit and opening its doors to a class of six students in 1841. Now there were 450 young men on campus, many from Michigan and others from Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin, New York and New Hampshire. There were a handful of students from Canada. Some 20 male professors filled the classrooms. The smattering of employees – librarians, janitors and a carpenter – were men.

U-M was hardly an outlier. The scene repeated itself on campuses throughout the country.

As historian Howard H. Peckham later wrote of U-M’s early decades: “No woman’s opinion was asked, no woman’s vote was cast, no woman was hired to assist or teach in it, and no woman was admitted to the student body. It was exclusively an intellectual male club of Regents, faculty, and students.”

Elsewhere in Michigan, women could be found learning alongside men on campuses: Hillsdale College, Albion College and Michigan State Normal College in Ypsilanti all had female students. And the Normal College had a woman on its faculty. These colleges were not, however, in the same standing as the University of Michigan; they were largely seen as places for training future teachers, and teachers of that day were almost always women.

(“They are merely high schools,” educator Catherine E. Beecher said of many colleges educating women in the mid-19th century. She helped found the American Women’s Education Association in 1852, the same year her sister Harriet was publishing a novel called Uncle Tom’s Cabin.)

In 1855, the Michigan State Teachers’ Association gathered in Ann Arbor and called for co-education at the state’s colleges and universities, specifically at U-M. Throughout Michigan, people began arguing that because U-M was a state institution – the “common property of all the inhabitants of the state” – its doors should be open to both men and women.

While U-M did not allow women, it promoted itself as a university for the everyday young man, unlike other institutions that limited their admissions to the rich and privileged. Whether offering training in the sciences or the classics, U-M “is freely opened to all the people, without distinction” and “meets the wants of the people, in all the higher degrees of education.”

Now some of those people wanting a university degree were women. And that was altogether a different matter for the Board of Regents. The women’s rights movement that had been percolating across the nation for the past decade had burst onto the campus doorstep.

When Burger’s letter was first presented to the governing board in March, regents set it aside for the next meeting in June. At that springtime session, two regents said they were open to admitting women, as did Gov. Kinsley S. Bingham, who happened to be attending the meeting. All other regents, and President Henry P. Tappan, opposed the idea. While there is no record of the discussion, the Detroit Free Press reported “an active and stormy session” ensued.

In Tappan’s eyes, a woman attending a university alongside men amounted to “something mongrel, hermaphroditic.” Women simply were not built for an advanced education, he believed. “When we attempt to disturb God’s order,” he wrote, “we produce monstrosities.”

Rather than making a final decision, the board established a three-man committee to study the idea of admitting women. The trio would have the summer to come to a recommendation.

-

Chapter 3 “A Sad Exigency”

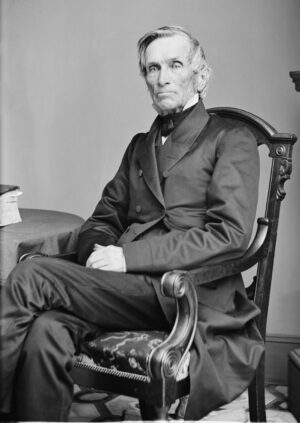

When he stood before his colleagues in late September, Regent Donald McIntyre held the 14-page “Report on the Admission of Females” instigated by Sarah Burger’s request for admission.

McIntyre, along with Regents Luke H. Parsons and Benjamin L. Baxter, had turned to university presidents across the country – all men – for their opinions on disrupting all-male institutions with the presence of women. They consulted the presidents of Dartmouth, Virginia, Columbia, Union College, and elsewhere. They also sought out ministers, politicians and professors. They approached no women.

Whether the Board of Regents admitted women or not, McIntyre said, it would no doubt be pilloried. “According to the various views and opinions entertained by the friends and opposers of the measure, its decision involves the destruction of the University on the one hand, and the grossest injustice to the young ladies of Michigan on the other.”

He struck an empathetic tone in reading the report. “Young ladies who have sat in the same class and recited the same lessons to the same teachers with young men, see them leave the Union School with no better scholarship than themselves and enter the University without obstacle and without objection, and when they ask to be admitted and are refused, they wonder why it is?” he said. “They desire to pursue their studies and see the tempting opportunity of doing so in the University, if they could only be admitted to improve it … They very properly address this inquiry to the Board of Regents, and respectfully request an answer.”

The replies from presidents of other universities were hardly surprising, although a few stood out for their progressivism. Most university presidents strongly opposed the idea of men and women attending a university together; a women’s college was fine, but allowing females to study alongside men “is considered inexpedient.” A separate-but-equal approach was best, they said.

The leaders of Harvard and Yale were firmly opposed to admitting women. “Of what use degrees are to be to girls I don’t see, unless they addict themselves to professional life,” said Yale’s Theodore Dwight Woolsey.

Allowing women into a university would obliterate their “refined and retiring delicacy,” warned the president of Rutgers College, Theodore Frelinghuysen. “Its propriety is very questionable, and its probable effects upon the interest and reputation of the University, I should fear. If necessity required such a step for female education, I should regard it as a sad exigency.”

The most encouraging words – and they were thick with caution – came from the presidents of Oberlin College, which had begun admitting women nearly two decades earlier, and Antioch College, which opened its doors to women in 1853.

Antioch’s Horace Mann said a woman “has as good a right to an education as man, even better if only one of them could be educated,” and the co-education “experiment” on his campus had been a win-win for students. Interacting with women smoothed the rough edges of men, he said. And young ladies came to see the “duties of life” placed upon men, an experience Mann said “has a strong tendency to expel all girlish romance and to exorcise the miserable nonsense which comes from novel reading.”

Still, Mann’s endorsement came with strong warnings: It was essential, he said, that someone always keep an eye on young men and women when they were together. He would rather a woman not be educated than go unsupervised on campus. “Are your President and Faculty in a state of mind to exercise vigilance over the girls committed to their care as conscientiously as they would over their own daughters or sisters?”

Charles G. Finney, president of Oberlin, agreed. If U-M planned to admit women, “You will need a wise and pious matron with such lady assistants as to keep up sufficient supervision. You will need a powerful religious influence to act upon the whole mass of students.” Once firm boundaries have been set, he said, “the young ladies and gentlemen exert upon each other a powerful influence for good and none of consequence for evil.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Donald McIntyre's first year as a regent threw him into the debate about whether to admit women. -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

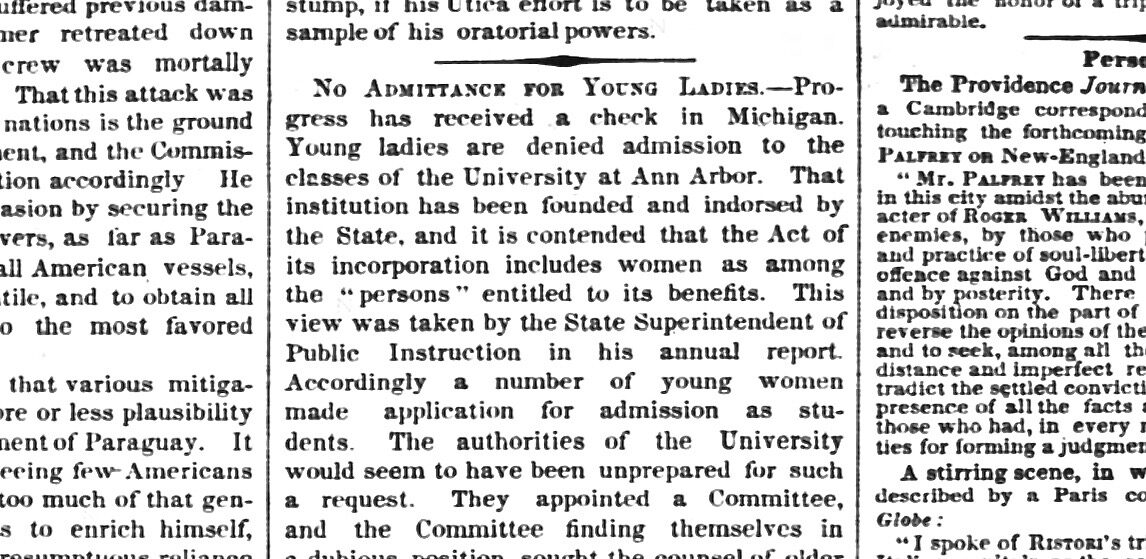

Theodore Frelinghuysen, president of Rutgers College, said admitting women would hurt a university's reputation.Image: Library of Congress

-

-

Chapter 4 “Corrupting Thoughts”

The unwritten fear of Mann, Finney and other presidents was palpable: Sex.

It was one thing for boys and girls to attend primary and secondary schools together. But “young men and women at college are different subjects” and the result could only be “corrupting thoughts” and worse.

McIntyre worried aloud about the wild behavior of college boys. “There is a period in the lives of many young men while passing from the innocent ignorance of childhood to the sobriety and decency of manhood when they have a strong tendency to low, gross, and vulgar thoughts, and impure imaginings,” he said. “Thrown together in a society by themselves, away from the restraining influences of home, they stimulate each other to debasing thoughts, words, and deeds; and their souls receive a stain from which years cannot restore them …”

Perhaps, McIntyre offered, the best way to corral young rogues “is the society of modest, virtuous women.”

Mann was the one president who spoke most forcefully about the benefits of co-education. But he also voiced the deepest concerns. “The advantages of a joint education are very great. The dangers of it are terrible. Unless those dangers can be excluded with a degree of probability amounting almost to certainty, I must say that I should rather forego the advantages than incur the dangers.”

U-M’s regents, if in favor of admitting women, would need to be vigilant about supervising the sexes. “Can you make yourselves secure against clandestine meetings?” said Mann. “And also against clandestine correspondence, reasonably so, for absolute security is impossible.”

A “high tone of moral sentiment” was expected of everyone on campus, Mann said. Antioch had no use for professors who “drink wine and use tobacco, practice loose conversations or manners in any respect” because of the poor example it would set for students.

He added: “We have no rowdyism, no drinking, no profligacy. We will not have it. Rather, regularity, sobriety, and an observance of the decencies and proprieties of life give elevation to public feeling and conduct which is a great safeguard and guaranty against the indulgence of passion.”

Mann realized his warnings may have sounded ominous, but said successful co-education demanded an unusual level of alertness. “You may think these are collateral matters. I think they are vital to the question. We never have had here the happening of one of those events mildly called accidents, but it is only because of our constant sleepless vigilance.

“Our security,” he said, “has arisen from our care.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Antioch College President Horace Mann believed co-education brought both rewards and dangers.

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Michigan's decision to deny admission to women students was reported by the New York Times.Image: New York TimesChapter 5 “For the Sake of the Ladies”

The perceived dangers and dire predictions were all too much for the men around the table.

McIntyre and his committee members had said it was fine – indeed, it was encouraged – for women to receive an advanced education. But such learning should take place in a separate setting. Throwing together the sexes “would tend to unwoman the woman, and thus produce deplorable effects in all spheres of life, private and national.”

For all the supportive words he provided about women obtaining a university education, it was still McIntyre who recommended shutting them out of Michigan.

“The true reason why this measure is opposed by the President and the Professors, by Regents, and by persons connected with other universities and colleges, and by good men and women everywhere,” McIntyre said, “is not because they do not wish women to be educated and thoroughly educated, but it is for the sake of the young ladies themselves and for fear that though some might pass the trying ordeal unharmed … they would lose more than they would gain by the experiment.”

The regents concurred with many of the presidents consulted, that co-education would only demoralize the men and give young women false hopes about their role in the greater world. The University was not prepared for the “complete revolution” required if women were admitted, a nod to the warnings of other presidents who equated female students with the expense of separate classrooms and housing, as well hiring women staff.

The vote was unanimous: “We think it wiser, under all the circumstances both in respect to the interests of the University and the interests of the young ladies, that their application should not be granted and that at present it is inexpedient to introduce this change into the Institution.”

There is no indication that Sarah Burger or any of the potential applicants were at the September meeting when the Board said it was acting in the best interests of women.

At present it is inexpedient to introduce this change into the Institution.

– Board of Regents, Sept. 28, 1858 -

Chapter 6 No Means No

Nine months after rejecting Burger’s application in September 1858, Regent McIntyre presented a petition signed by nearly 1,500 state residents asking that U-M admit their daughters and sisters. He also handed his colleagues a second admissions application from Sarah Burger and three other women.

Regent E. Lakin Brown wasted no time responding. The Board, he said, “sees no reason to change the action already had upon the subject of the admission of females to the University.”

Sarah Burger and her companions again were rejected. Regents also voted to print 2,000 copies of their earlier report denying admission to women. They wanted it published and circulated throughout the state.

It would be another 11 years before the University opened its doors to a woman. Regents voted 7-1, in early 1870 to admit women. “Many will think this a bold step, many will think it hazardous,” said Acting President Henry Frieze, “but no one who considers the relations of this University to the State and community will deny its entire justice.”

One woman, Madelon Stockwell, took her seat in a classroom in February 1870; seven months later, another 34 women joined her. Elizabeth M. Farrand, who was working in the University Library at the time and who later wrote one of the earliest histories of the University, called them “a trusty band of pioneers.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Sarah Burger Stearns, left, and Augusta Jane Chapin were vocal advocates for women's rights.Chapter 7 The First Applicants

The first pioneers, of course, were the women of 1858 who pushed for admission. In addition to Sarah Burger, records show the names of two others: 17-year-old Harriet Ada Patton of Ann Arbor and Augusta Jane Chapin, a 21-year-old from Lansing who had studied religion at Olivet College. Of the remaining nine women alluded to by Burger, their names are unknown.

The University eventually admitted Patton and Chapin. Patton became the second woman to graduate from the Law School, earning her degree at age 31 in 1872. She passed the bar, but there is no indication that she ever practiced. She lived in Ann Arbor and was known to attend class reunions. She died in 1927 at age 87.

Chapin received a master’s degree in 1884, when she was nearly 50 years old, and went on to become the first woman in the country to hold a doctorate in divinity. A Universalist minister, she preached in Michigan, Illinois, Iowa and Pennsylvania. When she died at age 68 in 1905, the Associated Press remembered her as “one of the best-known woman’s rights agitators in the country.”

Twice rejected by U-M, Sarah Burger enrolled at Michigan State Normal School in nearby Ypsilanti and graduated in 1862. A year later, she married Ozora P. Stearns, who had graduated from U-M the same year she first asked to be admitted and then earned a law degree. They made their home in Minnesota, where Ozora became mayor of Rochester and served as a judge. Sarah made a career of fighting for women’s rights, including founding the Minnesota Woman’s Suffrage Association and serving as its first president and later serving as a vice president of the National Woman Suffrage Association. She was 67 when she died in 1904.

Sources: Proceedings of the Board of Regents; Donald McIntyre papers, 1858 and 1863, Bentley Historical Library; A Dangerous Experiment: 100 Years of Women at the University of Michigan, by Dorothy Gies McGuigan; Toward Camelot: The Admission of Women to the University of Michigan, by John Parker Huber; A History of Women’s Education in the United States, by Thomas Woody; History of the University of Michigan, by Elizabeth M. Farrand; Henry Philip Tappan, philosopher and university president, by Charles M. Perry