Just Nuts

By Kim Clarke

Why, it’s some of my oldest friends – always ready to help when everything goes wrong – the squirrels in the trees.– Student Jim Barbour, a Michigan Union Opera character

-

Chapter 1 Revered

As they prepared to graduate, the University of Michigan seniors of 1903 had suggestions for improving their soon-to-be alma mater. Scholarships would be a nice addition, they agreed, as would some new professors and a bar in University Hall, the main academic building.

And this: “More squirrels.”

Michigan has had a very long romance with its campus squirrels, certainly since the days of the Diag as a scrubby wheat field filled with grazing livestock.

Through the years, the darting, chattering, pandering squirrels have been a happy diversion for students, staff and faculty. The family Sciuridae has been the subject of countless photographs and postcards (“early Ann Arbor settlers”), the recipient of nuts and chips, and a source of amusement and fascination for thousands cross-crossing the campus.

The U-M squirrel has been romanticized, serenaded, protected and parodied. It has its own campus club, which is more than any dog or cat can claim. One would think there was little teaching or research taking place, but only plenty of weighty pondering of the ubiquitous rodent.

Witness Frank E. Robbins, editor of the Michigan Alumnus Quarterly Review, writing in 1958:

“A friend tells me that one of the many squirrels inhabiting our campus has lost all but about an inch of its tail, but still runs about as if nothing had happened, happily fulfilling all the usual functions of a squirrel. All but one, that is — the etymological one; for our word ‘squirrel’ is remotely derived from a couple of Greek words (skia, shade, and ouros, tail) via Latin, Vulgar Latin, and Old French, and is supposed to signify that the critter can sit in the shadow of its own tail.

“So the question arises,” Robbins continued, “can this particular specimen still claim full membership in the international brotherhood of squirrels, or must he or she enter the emeritus status?”

The sorority girls of Delta Delta Delta loved the squirrels of 1952, or rather knew that the squirrels loved them.

“All the squirrels in Ann Arbor welcome us,” the sorority wrote in the Michiganensian. “No wonder they’re happy to see us. They eat our cigarettes. They chew our curtains. They bum our crackers.”

Before the Diag, the block M and the maize and blue, Michigan had its squirrels. They are simply part of the U-M experience.

“An afternoon drive through Ann Arbor residence streets above and at one side of the Campus is a very pleasant relaxation; it soothes with the suggestion of amplitude of time, largeness of aim and quietness of endeavor,” wrote the Michigan Alumnus in 1915. “And where else in the world will squirrels tag you along the streets begging for a nibble of food?”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Feeding squirrels on the Diag in about 1913.Image: Courtesy of Barry LaRue.

“All the squirrels in Ann Arbor welcome us.”

– Delta Delta Delta in the Michiganensian -

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Field notes on the fox squirrel in Livingston County, Mich., recorded in 1935 by U-M Zoology Professor W.H. Burt.Chapter 2 Studied

In the early days, as the University worked to establish its hold in science and research, squirrels were for study and exhibition. But first they had to be caught.

Alexander Winchell, professor of geology and natural history, ran advertisements in the state’s newspapers in 1856.

“The University Michigan is desirous of obtaining complete series of specimens illustrating the Natural History of the State, and as this object can be effected only through the cooperation of many individuals, it is hoped that every person into whose hands this circular may come will conceive an interest in forwarding some part of the enterprise.”

Among the “specially desired” mammals: squirrels.

“Those are desired in large quantities and of all ages, and procured at different seasons of the year. Small mammals may be preserved by throwing them as caught into alcohol. The large, (as foxes, wolves, &c.) must be skinned, (retaining feet and skull) and the skin thoroughly rubbed over with arsenic,” Winchell wrote.

In 1867, Winchell reported that J.T. Coleman, a taxidermist in the natural history museum, presented the University with the gifts of a fox squirrel and a gray squirrel. They were built into an exhibit that also featured a mounted black bear and a lynx; the squirrels, stuffed and silent, tottered overhead in tree branches.

-

Chapter 3 Protected

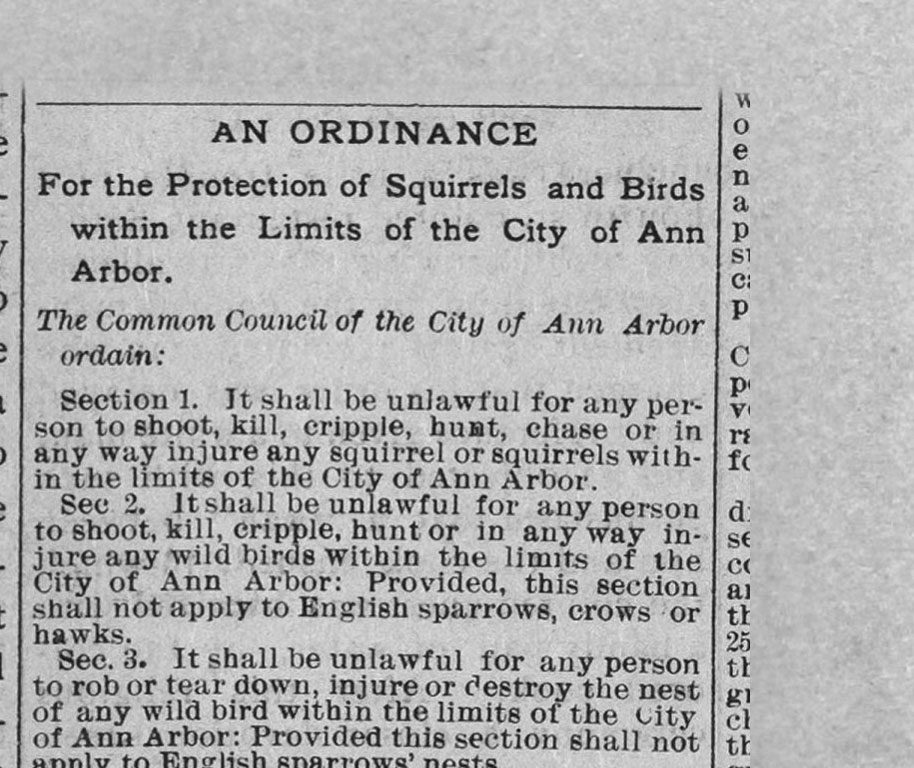

Some 40 years after the call for specimens, it became illegal to harm a squirrel in Ann Arbor.

The Common Council of 1894 unanimously passed an ordinance protecting the city’s squirrels and birds from hunters or anyone else looking to injure, maim or kill the creatures. Maximum punishment for offenders was a $25 fine and 30 days in jail.

But squirrels continued to be a target.

“Complaint is made that the squirrels on the campus are being shot by unprincipled persons,” the Ann Arbor Argus reported in 1896. “An example should be made of one or two of the nimrods.”

Probably the editors had no intention of implicating either the Ladies’ Aid Society of the First Congregational Church or the U-M faculty.

But it’s a fact that the Society’s 1899 “Ann Arbor Cook Book” included a recipe for squirrel. (“First catch your squirrel. Skin him, etc. Parboil in a little water in a kettle, add salt, pepper, and enough butter to fry it brown. Then eat. If the animal is tough parboil a little more till he is tender.”)

And when one Olney Belknap was fined $5 ($130 today) for shooting a squirrel in 1903, he told the judge that a “prominent university professor” had paid him to eradicate squirrels that were littering his lawn with pears.

In any case, it remains a crime to injure, torment, poison or kill a squirrel in Ann Arbor.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

A 2014 warning to students from University Health Service about squirrels and potential bites.Chapter 4 Feared

Delivering a campus health lecture in 1914, speaker Anna Scryver painted an ominous scenario. Ground squirrels were running amok in California and carrying fleas, which in turn carried disease.

“I fear for the future of Ann Arbor if the hundreds of tame squirrels now at liberty on the campus of the university are permitted to roam as at present,” she warned. “Is there any reason to doubt that sooner or later our tame squirrels will become bubonic plaque carriers?”

The editors at the Detroit Free Press could only roll their eyes – and sharpen their pencils.

“Mrs. Scryver seems to be a good deal in the position of the bachelor lady who wept for fear that if she married and had a son he might be drowned.”

There is no evidence of bubonic plaque in Michigan, and fretting about fleas on California squirrels bringing disease halfway across the country was currying unnecessary alarm and absurdity. “Still if anyone in Ann Arbor really feels nervous we suggest that he procure a squirt gun and occupy the silly season treating the squirrels of the little village to showers of antiseptic solution.”

“I fear for the future of Ann Arbor if the hundreds of tame squirrels now at liberty on the campus of the university are permitted to roam as at present.”

– Anna Scryver -

Chapter 5 Politicized

The poet Robert Frost had barely settled in as a visiting faculty member in 1921 when a conversation about campus squirrels turned into a local kerfuffle about nature, death and God.

When informed that Ann Arbor’s squirrels were dying off due to an unknown disease, Frost theorized it was “nature’s way” of correcting overpopulation. “Animals breeding rapidly after at time become a menace for one reason or another. Then comes a scourge and they die off.”

He then suggested that famine, disease and war have a similar impact when the human population grows too large.

A local paper was indignant. Where Frost implied “nature’s way,” the Washtenaw Post heard “God’s way.”

“How simple. The great war was nothing to be regretted, but simply God’s way of thinning us out!” the paper editorialized.

“The University of Michigan is welcome to Mr. Frost and his theory of God’s way. But there will still be those who believe it is the ignorance of man rather than the goodness of God that brings these scourges upon us.”

The squirrels had no comment.

-

Chapter 6 Serenaded

The campus squirrel has received no more noble treatment than in a Michigan Union Opera staged in 1911.

Seniors Joseph Hudnut and Julius Wuerthner composed the ode “The Squirrels in the Trees” as part of “The Awakened Ramses,” the tale of a mummy come to life on campus. When a character fails in love, he finds solace in the squirrels, “my oldest friends—always ready to help when everything goes wrong.”

The Squirrels in the Trees

When I am up against it hard

And dictionaries fail

I seek the squirrels in the trees

—And thereby hangs a tale.

Dressed in their nobby sets of furs

They’re chipper as the lark

And things they see that most of us

Are careful to keep dark.

You’ll never find them off their nut —

Ask anything you please —

You’re sure to get an answer from

The squirrels in the trees.The verses go on and on — and on — before concluding:

The author of our opera wished

To read it to some girls,

Of course, they wouldn’t listen, so

He read it to the squirrels.

Those gentle critics only sighed

And winked an eye at Joe

“An easy way to fame,” they said

“Next year we’ll write the show

“If Hudnutisms make a hit

“We surely ought to please

“We, too, can crack some chestnuts,”

Said the squirrels in the trees. -

Chapter 7 Gorged

The glut and girth of Ann Arbor squirrels have never failed to amaze.

Zoology Professor Joseph Beale Steere provided an inventory of Ann Arbor mammals to the Ann Arbor Courier in 1880, taking special note of the profusion of fox squirrels and their affinity for the home of fellow faculty member Andrew Ten Brook. The home was located at the corner of South University and Washtenaw avenues, the site of today’s Phi Delta Theta house.

“It is quite abundant in this vicinity, and has been so long protected about the houses of Prof. Ten Brook and Mr. Scott, that is has become half tame, and is frequently seen in other parts of the city. It is usually solitary in its habits, but in the spring large numbers sometimes assemble for some unknown purpose. I saw at least fifty gathered in this way, in the spring of 1877, I think, near Prof Ten. Brook’s house, and other speak of still larger gatherings.”

The pampered life of the squirrel continued as the 20th century unfolded in Ann Arbor, where local realtors made them a selling point. “…[T]ame fox squirrels can be found in large numbers in most of the yards in our city. They are so tame that students carry nuts in their pockets and the squirrels come up and take them out of their hands. They build their nests in the trees and about the dwelling houses all over the city.”

Flash forward to the 21st century and Michigan Daily columnist Sarah Rubin:

“The most striking characteristic of the squirrels on campus is their relative size. I come from a nearby small town in Michigan, and our squirrel population isn’t nearly as overweight. The squirrels in my town live in trees. They jump and run on the phone wires and all of the other typical squirrel behavior that looks like it’d be fun to try if I was 3 inches tall.

“Here, in Ann Arbor, the squirrels are always on the ground. Why?

“Because they’re freaking obese. You have to do a double take to see if it’s a cat or a squirrel walking with you to class. They’ve lost their aero-dynamic powers and they’re too fat to ascend, so they stagnate in the grass.”

“They’re freaking obese. You have to do a double take to see if it’s a cat or a squirrel walking with you to class.”

– Sarah Rubin, Michigan Daily columnist -

Chapter 8 Beloved

From his fourth-floor office in Angell Hall, Classics Professor Eugene S. McCarthy spent hours watching the squirrels outside his window. He then regaled Michigan Alumnus readers with the animals’ escapades in a series of articles about Tail-in-Air and his companions Shadow-Tail, Peter Pan, Topsy, to name a few.

“Tail-in-Air has ‘it.’ All my visitors are attracted by him, and they go to the window to make his more intimate acquaintance,” McCartney wrote in 1935. “Friends who know both him and me are now more solicitous about his health than about mine.”

McCartney was editor of scholarly publications for the graduate school. His office windows faced State Street, but were largely obscured by the facade of Angell Hall that bears an inscription from the Northwest Ordinance. He went so far as to wander the roof of Angell Hall to determine just how the squirrels made their way to his window ledge, and then provided Alumnus readers with a detailed sketch of the building and the squirrels’ routes.

“When Tail-in-Air pours forth from the rainspout while I am editing an arid manuscript he is as refreshing as rain during a drought,” he wrote. “He is always welcome, for he makes lighter the burdens of this workaday world.”

McCartney wrote three articles over the course of a year, each one longer and more detailed than its predecessor. His affection for Tail-in-Air and other squirrels bore a timeless quality echoed by all generations on campus.

“I have often paid much more for far less cheer and pleasure and entertainment than my little hyphenated chum provides. I shall do my best to merit his continued confidence and esteem. If the tie that binds is ever broken, he will have to do the breaking.”

This article was drawn chiefly from the Michiganensian; Michigan Alumnus; The City of Ann Arbor, by Noah W. Cheever; Ann Arbor Cook Book, by the Ladies’ Aid Society of the First Congregational Church; Michigan Union Publications collection at the Bentley Historical Library; and contemporary news accounts.