J-Hop’s Rise and Fall

By James Tobin

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

There is a band playing no matter what anyone tells you and if you don’t believe it just go up to the hospital and ask someone who got there early and saw it before the crush of the crowd got them.– Student Roy Heath

-

Chapter 1 “Oh, Let It Die”

The hard decision had been put off for as long as possible.

Now the existential question of J-Hop – whether to keep it on life support for another year or let it die – had finally landed on the weekly agenda of Michigan’s Student Government Council. It was a chilly Wednesday night, May 11, 1960.

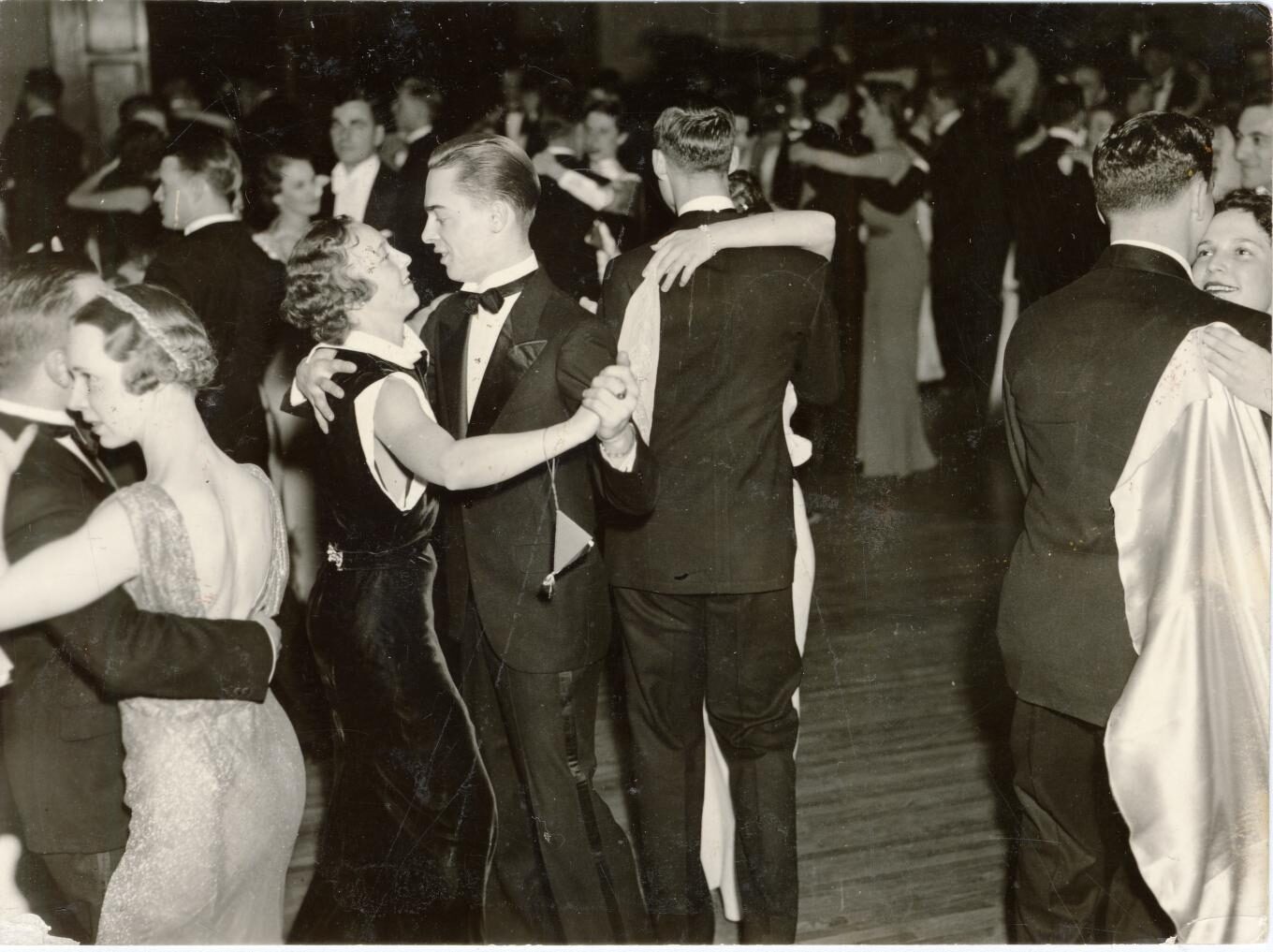

Since its founding almost a century earlier, the mid-year social event that became known as the Junior Hop, then simply and universally as J-Hop, had swelled into a glittering three-day-and-night festival of big band dances, house parties, hayrides and morning-after breakfasts. To generations of living alumni, the spectacle of J-Hop occupied a pedestal in Michigan tradition just one level lower than varsity football itself.

So this would be no easy decision for 16 student politicos barely out of their teens and with no great store of respect among their peers. The prevailing view of student government was voiced by a critic who said student government was “run by a bunch of hams for a lot of don’t-give-a-damns.”

Indeed, not to give a damn was very much in vogue just then. Dressing for dinner was out. Creased pants were out. Rah-rah was out. The new place to go for live music was The Promethean, a coffee house on Liberty with dark gray walls and deliberately mismatched furniture. No dance music there, just mournful folk songs, and the beverage of choice was muddy espresso.

J-Hop? In this age of apathy?

One student said J-Hop was “so OUT even the OUT people won’t touch it.”

As recently as 1955, there had been the usual fierce competition for 1,350 J-Hop tickets, one ticket per couple, the maximum crowd that could squeeze into the Intramural Building’s giant gymnasium.

But since then, ticket sales had dropped by nearly two-thirds. By 1959, said Murray Feiwell, that year’s forlorn J-Hop chairman, “we did everything but line people up at the administration building and take seven dollars out of their pockets.”

In desperation, the 1960 affair had been downsized and shifted to the smaller ballroom at the Michigan League.

“Oh, let it die,” begged a Michigan Daily editor. That was “the most merciful thing you could do to the fine old Michigan tradition, J-Hop.”

So the members of the Student Government Council trudged upstairs to their office in the Student Activities Building and started the debate about what to do. They had a lot of history to consider.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

In early years J-Hop featured an assemblage of the attending couples in a human block-M, as in this photo from 1920, taken in Waterman Gymnasium.Image: Bentley Historical LibraryChapter 2 Origins

The holding of a mid-year student dance – a private affair with no special sanction from the University – had begun in the misty past of the late 1860s, just before women were admitted to U-M. (Male students invited sweethearts from home, paying their railroad fare and putting them up in chaperoned digs.) From one year to the next the event moved from the Gregory House, a hotel on the city’s old courthouse square, to Hank’s Emporium, then Hangsterfer’s, both downtown saloons.

The organizers of these early affairs were U-M’s nine original fraternities, known collectively as the Palladium. In the early 1890s they moved the dance to the larger setting of Waterman Gymnasium, just constructed at the southwest corner of North and East University Streets.

That changed things. Putting the dance on University property meant faculty had the final say over how the dance would be run. The nine original frats rebelled by holding their own dance in Toledo in 1896. But they came back a year later, upholding their honor by sponsoring elaborately decorated booths emblazoned with their emblems, a practice that lasted for decades.

As the student population swelled, so did the Junior Hop. (Off and on, juniors were in charge of organizing the dance, with the idea of honoring the outgoing seniors. Even when that tenet waned, the name “J-Hop” stuck.) By the early 1900s, it was firmly in place as the crowning event of each year’s social calendar.

One night of dancing expanded to two, with parties before and after. Each year, more tickets were sold. Decorations and lighting became more elaborate. Programs were printed. Faculty “patrons and patronesses” were invited and feted. Favors and keepsakes were handed out. Then “the Hop itself comes, and what a reign of bliss it brings!” wrote a student satirist in 1906. “There is the blare of music, the glare of lights… There is My Lady Talcum, vivacious, in her new gown. And by her stands My Lord White-Gloved Discomfort, brilliant in patent leathers, wash tie, and a coat with most expressive long tails…”

At the start of the 20th century, J-Hop combined a restrained romantic ambiance with visual spectacle. Overall, it was a decorous affair of which even a concerned parent might approve.

Then came the ingredient that turned J-Hop into a craze.

The ingredient was jazz, in one form after another, developed largely by successive generations of black southern musicians and seized upon by successive generations of white northern youth.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

In 1922 a cartoonist for The Chimes, a short-lived U-M literary magazine, sketched a J-Hop couple exchanging glances in the "flapper" era of bobbed hair and temporarily short skirts. The caption was: "Lisa Thinks the Hop Great Fun."Chapter 3 Dirty Dancing

In 1913 the decorative theme of J-Hop was “a shrine to Terpsichore,” the Greek muse of the dance. But old Terpsichore never saw some of the steps students were doing out on the floor of Waterman Gym as the hour grew late.

In fact, “fancy holds” and “feature dancing” had been raising chaperones’ eyebrows for several years. Ragtime, the irresistible new music that encouraged wild departures from the Victorian holds of the 1880s and ’90s, had brought a nationwide fever for such steps as the Bunny Hug, the Grizzly Bear and the Turkey Trot, all of which required varying degrees of hugging and grinding.

Most scandalous of all was the “clutch hold” of the tango. Student authorities had already been talking about banning it just to preempt a crackdown by the faculty.

As midnight approached, something rowdier than dirty dancing was brewing outside the gym.

For some years, J-Hop organizers had allowed people not attending the dance itself to gaze upon the spectacle from Waterman’s upper galleries. Then, as the dance came to a close, the doors would be opened for the spectators to walk through and admire the decorations.

But this year, the J-Hop central committee had decided to keep the gallery off-limits and the doors locked. This did not go down well. A number of well-oiled men outside now decided to attend J-Hop by force. With a heavy length of gas pipe, they battered the doors open. Once inside, they found themselves facing a phalanx of intrepid campus janitors and a U-M purchasing agent named Loos. Wielding make-shift clubs and at least one fire extinguisher, Loos and his men held off the unarmed intruders for twenty minutes, long enough for eight of Ann Arbor’s finest to arrive and bring the skirmish to an end.

Outrage grew over the next few days. Newspapers, alumni and the University’s out-state critics seized on the brawl as only the most flagrant of J-Hop’s excesses.

Finally the faculty senate voted to do away with J-Hop altogether “until such time as the university authorities are satisfied that all objectionable features will in the future be eliminated.”

They intended not only to prevent more violence but to curb J-Hop’s extravagance, “ragtime and low vaudeville music,” and “objectionable dancing.”

Poor Willis Diekema, general chairman of J-Hop that year, said no mere committee could have resisted the J-Hoppers’ determination to dance the tango in 1913.

“Because of the extreme popularity of the tango,” he pleaded, “the objectionable dancing could have been checked only by the action of police.”

The faculty stuck to the ban for only one year. J-Hop was reinstated in 1915, then rolled along as ever through the years of World War I.

In 1920 there was more trouble. Unescorted “flappers” – young women who insisted on their rights to pleasure, self-determination and cigarettes – crashed the affair, displayed “scantily clad forms” and engaged in “drinking, smoking and individual caddishness.”

There was another one-year ban and another reinstatement, this time with a long list of rules. But the demand for tickets only grew.

Then in 1928 the giant Intramural Building on Hoover Street opened its doors. When J-Hop’s organizers saw the cavernous main gym – 252 feet long, big enough for four basketball courts – they reserved the space with stars in their eyes.

This was where J-Hop would enter its golden age.

Most scandalous of all was the 'clutch hold' of the tango. Student authorities had already been talking about banning it just to preempt a crackdown by the faculty.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The great swing jazz bandleader Tommy Dorsey entertains the crowd at J-Hop in 1948.Image: Bentley Historical LibraryChapter 4 When Swing Was King

The kingpins of the J-Hop Committee now did some figuring.

With the IM Building’s huge gym for a venue, they could sell tickets to many more couples at the long-prevailing rate of $7 per ticket – enough to pull in $7,000 to $8,000 in revenue (roughly $100,000 in 2018 dollars.)

That was enough to hire the best bands in America, and not just one great band but two, even three.

Ragtime was out. The new music was swing jazz. It was as hot on college campuses in the 1930s as rock and roll would be 20 and 30 years later.

Now J-Hop put students on a dance floor within a few yards of their musical deities – Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Count Basie, Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey. This was like having the Beatles play for your high school prom in 1965. If you loved swing and you could scratch together $7, Depression or no Depression, you would fight like hell for a J-Hop ticket.

Typically now, two bands would set up, one at each end of the gym. They would trade off, each playing half-hour sets, each fighting the other to whip the crowd to a higher plateau of excitement. It drove U-M’s swing aficionados into raptures.

“Twenty years from now,” a swing worshipper told Daily readers in 1941, “Goodman may be remembered only vaguely as the beginner of a movement known as swing, some mad, senseless rhythm that died out …” Not likely, the reviewer said. Instead, “he may be lauded as the father of … something more moving and beautiful than has ever before been found in folk music.”

Every year now, students would wait for weeks to hear which bands the J-Hop committee had landed. In 1931 the Detroit radio station WJR began to broadcast the spectacle live from 11:30 p.m. to 1:30 a.m., with Professor Waldo Abbot of the Department of Rhetoric offering song-by-song commentary. By the time the swing era began to fade in the mid-’50s, J-Hoppers had danced to virtually every big-name band in the country.

* * *

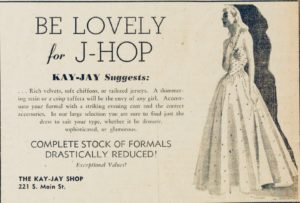

If swing was king in the court of J-Hop, fashion was queen. Intense attention and no little money were devoted to the question of what to wear. For men, that was easy. Tuxedos and tails were standard. Women had to choose not only their gowns but accessories, jewelry and the proper arrangement of one’s hair.

Fashion took center stage at J-Hop’s Grand March, where the couples lined up to circumnavigate the floor. The J-Hop chairman (always a man) and his date led the procession. All this would be written up in the Daily as if it were a royal wedding, with the closest attention to descriptions of what the leading ladies wore.

The Daily’s reporter intoned in 1935, “The climax of the evening, the grand march, was led by Winifred Bell, ’36, and Edward Litchfield, ’36, general chairman. Miss Bell selected a charming robin’s egg blue uncut velvet formal, made in the Empire style. It featured a short bodice and a full skirt, with a short train, while the neckline was trimmed with a draped collar, shirred at the front which outlined the V-neck. She wore a rhinestone clip at the neck, with matching earrings and bracelet. Her shoes were white velvet, trimmed with silver, and she wore a black velvet wrap with a white lapin ascot collar.”

And that was just one of twenty women’s outfits described for readers of the next day’s Daily, from Miss Bell’s rather complicated ensemble to Jean Greenwald’s raspberry waffle-weave crepe to Margaret Mustard’s flowered satin with high Peter Pan collar.

“The dark blue of the ceiling decorations provided an effective background for the vivid colors and dainty materials. Glittering trimmings of lame and sequins and accessories of gold and silver reflected the maize colored lights” – a spectacle that made that year’s J-Hop, like every J-Hop, “the most brilliant social event of the year.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Urgent needs are expressed in two Michigan Daily want ads placed in 1940.

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

In 1938 the Daily plotted the typical male experience of J-Hop as a roller-coaster ride between extremes of exhilaration and depression.Image: The Michigan DailyChapter 5 Mornings After

There were big dances at U-M all year long in the ’30s – the Freshman Frolic, the Senior Ball and many more.

But J-Hop was much more than a single big dance. It stretched across three days and nights. Associated meals and parties spread across the campus and beyond. Virtually every fraternity held at least one house party, and many gave breakfasts that began shortly after the last dances of the night. A big breakfast was served at the Union starting at 1 a.m., organized chiefly for “independents” — students not affiliated with fraternities or sororities. That, too, was a reservation-only affair. Cost: 75 cents.

Hayrides, sleighrides and sledding expeditions got the revelers out for some fresh air in the Arboretum or along the Huron. After the after-dance breakfast, J-Hoppers rolled from one hamburger joint and bar to another until the breaking of dawn.

The sheer physical ordeal left many a survivor exhausted. In 1939 a J-Hop veteran named Roy Heath compared it to 15 rounds in a championship boxing match. “To say I don’t know anything about J-Hop is to say Max Schmeling doesn’t know anything about Joe Louis,” he told readers of the Daily.

Heath offered point-by-point advice for neophytes.

First: The cash needed.

“C’mon … cough up that watch. Don’t kid yourself, it will cost just double what you think it will.”

Then, “on the night of the battle,” for courage, “you should prepare a sort of a pick-me-up to sip when the going gets rough. It consists of six parts Scotch, one part pure alcohol, three parts extract of Tiger blood and four parts iron pyrite.”

Thus fortified, one could proceed to the main event. But only the bravest souls, Heath advised, would let themselves in for the full four hours. It was much wiser to save two hours of strife by arriving at midnight. But then you had to prepare for a deafening assault on the eardrums.

“There is a band playing no matter what anyone tells you and if you don’t believe it just go up to the hospital and ask someone who got there early and saw it before the crush of the crowd got them …

“As soon as the band starts to play a piece the news is relayed back. When the message gets to you, just whistle it softly to yourself and jiggle up and down.”

Afterward, there must be time to recuperate. “You will be as good a man as your grandfather was at the age of 90 in two months at the outside.”

* * *

Beneath the courtly surface there was a predictable mixture of drinking and sex – or attempts at it.

In 1939, Daily reporters sought out local cabbies for their take.

“There ain’t much petting going on early in the evening during J-Hop,” one confided. “At least, I don’t see any. No, man, when I’m driving, I’m driving. But I can’t help hearing things. And early in the night, the boys do get their faces slapped once in a while, and from the sound of things, some of those babes sure pack a mean wallop.

“Maybe it’s drunkenness or just plain appreciation, but the slapping sort of wears off later in the night.”

* * *

Appreciative or not, a woman was expected to send her escort a “bread-and-butter letter” – a thank-you note describing the wonderful time she had had. In 1935 the Daily prepared a handy cheat sheet with multiple-choice offerings that suggested the romance of J-Hop ’s was more often an ideal than a reality:

Dearest:

- Tom

- Dick

- Harry

- Phineas

I had a wonderful:

- hangover.

- cleaner’s bill.

- time with… (a) your roommate; (b) the chaperone; (c) Uncle Joe [Joseph Bursley, dean of students, who kept a stern watch from J- Hop’s sidelines]

I adored your:

- house party.

- brawl.

- cocktails.

It was all so:

- divine.

- tiresome (speaking frankly).

- exhausting.

And now I feel like:

- you looked.

- Hell!

- another Tom Collins.

A comparable note from the male point of view had been written years earlier by none other than Avery Hopwood (LSA 1905), who became the most popular American playwright of the 1910s and ’20s and bequeathed part of his fortune to start U-M’s prestigious Hopwood Awards.

In a short story, “After the Hop Is Over,” published in the Inlander, Hopwood’s fictional U-M man jots a diary entry about the morning after at one fraternity:

“The girls have gone. I’m almost dead. So are we all. The house smells of perfume, and there’s powder in the air… I got a crush on Miss Evans — Ratty’s girl. She made Jean [his own date] look like two cents. I’m in love, in love — and dead broke… Thank God the damned thing is over.”

* * *

For some, J-Hop was just a hubbub in the distance – someone else’s party.

Especially during the Great Depression, plenty of students could barely cover the cost of tuition and food. There was no J-Hop for them.

Others, by an unspoken understanding, simply were not welcome. DeHart Hubbard, the black track-and-field star who won a gold medal at the 1924 Olympics, told an interviewer years later that the tiny circle of African American students at U-M in the ’20s barely noticed the shindigs that were not “whites-only” by law but might as well have been.

“They would have the big – what do you call it? J-Hop or something?” Hubbard said. “We just didn’t bother about them.”

And there were students who hoped to get in on the fun but never could. The Daily’s classified ads one year carried this brief appeal: “WANTED: DATE FOR J-HOP. AM BLOND, 5’2”, BIG BLUE EYES. NO. 2-2591. ASK FOR DONNA H.”

* * *

Still, for the lucky and the privileged facing the cold, gray landscape of winter in Ann Arbor, J-Hop was a citadel of warmth and color.

“Didn’t we come back with rings under our eyes, a collection of prize pictures and guest towels, to say nothing about the favors and the fraternity pin?” mused a columnist in the Daily who used only her initials, J.C.X. “And then we woke up Monday A.M. to the tune of the alarm clock played in the dismal key of C minor, gazed out upon the cold cruel world and decided what’s the use anyway. Nothing exciting would ever happen again.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The Daily published dozens of J-Hop-related ads each year, including this one in 1940.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

At J-Hop in 1954, just before a long slide in ticket sales, dancers went in for the Bunny Hop.Image: Ann Arbor District LibraryChapter 6 “A False Note in the Old Melody”

J-Hop’s staying power was evident in the weeks after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. It was quickly announced that the event would stay on the calendar for February 1942.

But in 1943, with thousands of U-M men away at war, J-Hop was downsized, combined with the Senior Ball, reduced from three days to two, and renamed the Victory Ball. So it remained through 1945, a shadow of J-Hops of the ’30s.

With the war’s end, the J-Hop Committee for 1945-46 proposed a revival of prewar splendor – two dances, three big-name bands, house parties, breakfasts, the whole shebang. Total cost: $10,000, the highest budget ever.

There were qualms. The Student Affairs Committee, with its faculty majority, vetoed that plan on several grounds: it would strain Ann Arbor’s already overtaxed housing stock; there was a shortage of willing chaperones; such a luxury-fest would “look bad out-state.” The Committee approved a trimmed-down affair – one dance on a Friday; house parties on Saturday.

Some students diagnosed a more troubling flaw in the big-spending plan – a moral one. Did students really want to re-animate the make-believe luxury of J-Hop in the wake of a world war and in the shadow of the atom bomb?

“No one denies the delight of the proposed weekend,” said a letter to the Daily signed by 16 student critics. “Yes, and wonderful it would be to return to the gaiety of the old carefree days: to turn our minds from the sickening pictures of devastation and suffering abroad, to wrap our oceans around us more tightly, to preach not only America First, but Me First … But our ears detect a false note in the old melody.”

Nonetheless, in just one day the J-Hop Committee gathered 2,300 student signatures in favor of prewar J-Hop glory. A female graduate of 1945, married to a Navy man who had left Ann Arbor to serve and now was back as a student, demanded what she and her husband had dreamt of for four years – a real J-Hop.

“We feel most students want what we want: peacetime activities as soon as possible,” she wrote the Daily. “Sure, J-Hop as a two-night affair would be a $10,000 dance. But if the students want it – well, they’re paying for it, so let them have it!”

And they got it. In the late ’40s and early ’50s, J-Hop roared on. The great swing bands came back. The fashions became a little less formal, but the decorations were as lavish as ever, the parties as raucous as they’d been in the ’20s and ’30s.

But it was not to last.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The jazz superstars Duke Ellington and Louis Prima led their bands at J-Hop in 1950.

-

-

Chapter 7 “A Sweeping Lethargy”

J-Hop had become so big partly because Michigan itself had become so big. By the 1930s the student body had topped 10,000.

When the tradition began to fade, that, too, may have owed something to Michigan’s ever-swelling size.

In 1941 there were about 11,000 students. By 1950, thanks in part to the G.I. Bill, which brought crowds of World War II veterans to campuses across the country, Michigan’s enrollment swelled to nearly 20,000. In the late 1950s the number jumped again, to nearly 25,000.

In 1959, Erich Walter, a U-M graduate of 1914 who became a professor of English and dean of students, remarked that the “problem of bigness” had caused profound changes in the student’s experience of college life. An entering freshman on a campus so big felt tiny, even expendable. “The student is swept off his feet by the size of this place,” Walter said. And it was so big that “there is nothing to bring this community together.”

Football, maybe.

But not J-Hop. Not anymore.

“Especially in the past few years,” a Daily editor named Faith Weinstein wrote in 1959, “a kind of sweeping lethargy has become practically the sole unifying force among the students of the University.”

She blamed this on a rising “cult of the individual” and “a glorification of the personal, especially of the Personal Problem, and a deprecation of anything that concerns groups, with the possible exception of the group you drink with.”

In the midst of a mood like that, a great communal ritual like J-Hop didn’t stand much of a chance.

* * *

After a long discussion, the 16 members of SGC voted 9-7 not to place J-Hop on the campus calendar for 1961.

There was a small irony tucked away in that vote.

One of the seven who voted to save J-Hop was a student named Al Haber. He would soon stand at the center of forces that pulled students out of their apathy and swept them into a new era of campus energy quite unimaginable to the swing dancers of the 1930s and ’40s.

The following fall, Haber became the first president of the Students for a Democratic Society – SDS.

The online archives of the Michigan Daily provided most of the sources for this story. Parts of Chapter 2 are taken from the writer’s earlier story, published by Michigan Today, “The Year They Cancelled J-Hop.” The anecdote about Avery Hopwood is from Jack Sharrar, Avery Hopwood: His Life and Plays (1989.)