How the Michigan Union Came to Be

By James Tobin

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The new building is to be the place where the average student can get something of that extra-curriculum training which counts for so much.– U-M Alumni Association

-

Chapter 1 A Barstool Ambition

Late one night in the spring of 1903, a Michigan junior named Bob Parker had a big idea.

Admittedly, he was a little drunk.

He had spent a long session down at Joe’s, a saloon on Main Street much frequented by students. Now he was back in his boarding house on Lawrence Street. (Fittingly, it was Miss Gagney’s house, the one in which a music professor named Charles Mills Gayley composed Michigan’s alma mater, “The Yellow and the Blue.”)

Parker and his pals had been griping, not for the first time, about animosities between fraternity men and “independents,” between the seniors and the juniors and the sophomores, between the Lits and the Meds and the Laws. Why couldn’t they all just rally around Michigan itself?

What could be done? Parker asked himself.

“We wanted an organization ‘for Michigan men everywhere,'” he recalled long afterward, “an organization that would be the one recognized all-inclusive medium to tie up the loose ends, to centralize the Campus life, to bring us all together as Michigan men.”

Unlike most ambitions conceived on barstools, Parker’s survived the coming of the next day. Eventually, the idea was turned over to Irving K. Pond, a gifted, slightly eccentric architect who embodied Parker’s notion in the blueprints of a great building.

Both men, the student and the architect, were acknowledging a new reality.

From colonial times through the mid-1800s, there had been essentially two sorts of American colleges — finishing schools for sons of the wealthy and seminaries for ministers in training. Then the University of Michigan and its peers — the early public universities — opened the doors wider. They invited more students to be schooled for an urbanizing, industrializing society.

From 1850 to 1900, Michigan swelled from a few dozen students to several thousand, and the number was climbing fast. Those new students built a world separate from their professors’ classrooms and labs — a hive of societies and clubs, organizations and teams. In the new century, going to college now meant competing in a social sphere that would prepare students for the milieus they would encounter in business and the professions.

Parker the student and Pond the architect embraced that new reality and proposed to enhance it — Parker with a sprawling organization, Pond with a grand edifice.

The organization and the building would carry the same name: The Michigan Union.

Today people say the name and think only of the building. But the building never would have come into being without the organization. Bob Parker’s era is long gone. But the building is the physical remnant of that early-1900s movement to forge a new ethos for the “Michigan Man.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Bob Parker's senior photo from 1904.Image: Michiganensian 1904

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Faculty hoped the Michigan Union would help to channel rowdy male energies, which were unleashed for many years in semi-organized "rushes" — class-versus-class or department-versus-department melees like this one at Ferry Field in the 1910s.Image: Bentley Historical LibraryChapter 2 Segregation by Sex

Bob Parker tried his idea on a few friends. They liked it. He sounded out President James Burrill Angell, who gave his blessing. Next, Parker took the plan to his fellow members of Michigamua, a new honorary society of leading senior men. They endorsed it, spread the word in their circles, and hosted early meetings.

Parker enlisted several young professors, including the hard-charging Henry Moore Bates, who had just joined the law faculty. Bates had been quoted as saying that the campus needed “a common meeting place, not only for the material conveniences but also as a social and intellectual clearing house.” He became an energetic supporter.

It never occurred to Parker and his allies to include women either in the planning or the organization. That merely reflected the segregation by sex that prevailed across the campus.

Only males had attended U-M until 1870, when a handful of women were admitted. In that era, there were no dorms. For a time, both sexes conducted their lives outside class without University supervision and freely mixed. Men and women often lived in the same boarding houses and broke bread together.

But in the 1890s, when women made up 20 percent of all students, an informal alliance of feminists and faculty wives organized a Women’s League to offer women students their own organizations and activities. Soon women students were guided into female-only boarding houses approved by the League. A dean of women was appointed to supervise them.

By the time Bob Parker enrolled, male students lived in one sphere, women in another. They met and mingled only in classes and closely supervised social settings. Men dominated the major student organizations. The University, with its virtually all-male faculty, was still organized to educate men for an adult world in which men led the institutions and filled the ranks of business and the professions. Women, with few exceptions, were expected to move into the private sphere of home and family.

So when Parker ruminated about student rivalries and antagonisms, he thought only of men, and his solution was an all-male solution.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The building site of the new Michigan Union was assembled from adjacent lots on State Street at the intersection of South University. The home of Law School Dean Thomas McIntyre Cooley, used as the Union's headquarters from 1907 to 1917, was demolished. Next door, the childhood home of the Union's architects, Irving and Allen Pond, was taken down and moved.Chapter 3 “A Great Club and Center”

The idea was to provide “a great club and center for all student, faculty, and alumni activities.” It would draw in “all the societies in the University that care to affiliate with it” — not to govern their affairs, but to act as a coordinator and clearinghouse.

The club would need a clubhouse, a place for rest and recreation. That was the concrete goal. But the campaign to build a headquarters for the union of student organizations was meant to engender a more profound ideal. By bringing groups together to create a physical home for student life, the Michigan Union would engender a unifying “school spirit.” It would bind students and alumni to the University as patriots are bound to their country. In turn, it was hoped, tensions would dissolve between fraternity men and “independents,” Lits and Laws, the class of ’03 and the class of ’04, and so on.

“Primarily, we are here for work,” declared the editors of the Michigan Daily, who approved of Parker’s campaign, “but there ought to be a place in which the men of several departments could get together and become better acquainted… Unless a man is a fraternity man at Ann Arbor he has no very strong ties to bring him back to his Alma Mater in after years. A Union of this sort would tend to unite the spirit of the entire college, and would become in time as great a factor as athletics in keeping and bringing the men together.”

Parker and company plastered the campus with signs to advertise a mass meeting in Waterman Gymnasium. Eleven hundred showed up to join — a substantial portion of the whole student body — and the Michigan Union was launched. Articles of association were drawn up. Parker was elected the first president.

Fundraising ensued. Members paid annual dues of $2.50. They put on a carnival (later Michigras) in Waterman Gym and sold tickets; they staged shows and held dinners. Well-to-do alumni were targeted, though Parker beat back the idea of soliciting a handful of major gifts from millionaires. Instead, he wanted as many alumni as possible to take shares in the campaign.

At the same time, alumni were raising money for what would become Alumni Memorial Hall to honor the University’s war dead. (That building now houses the U-M Museum of Art.) This campaign confused matters and slowed the Union’s drive. But by 1907, there was enough money to buy a temporary home.

The Union chose a broad fieldstone house with three towering gables on the west side of State Street looking eastward down South University. For many years it had been the home of Thomas McIntyre Cooley, dean of the Law School and a justice of the Michigan Supreme Court. Remodeled by Professor Emil Lorch of the Department of Architecture (with crucial funding from Levi Barbour, a wealthy Detroiter and U-M regent), it had two dining rooms, a reading room, a large lounge, and rooms for games and meetings.

It opened as the first headquarters of the Michigan Union in November 1907, and it soon swarmed with events and activities — dinners, receptions, lectures, parties, and meetings by the dozen every month. The Union hosted visiting dignitaries. It organized a student council. It launched the student-run Michigan Opera. Professor Bates, who remained the Union’s chief supporter on the faculty, claimed that after only a few years, it was “conceded to be the most powerful, the most energizing and the most helpful factor in University life.”

The Cooley house was not big enough for the purpose. But it would do while the Union moved on with its grandiose long-term plan.

... there ought to be a place in which the men of several departments could get together and become better acquainted.

– The Michigan Daily -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Allen Pond (left) and Irving Pond (right) spent their lives in close association. In Ann Arbor they grew up together and attended the University of Michigan. Irving graduated in 1879, Allen in 1880. In Chicago, they formed the architecture firm Pond and Pond, which operated through the 1920s. Irving took the lead in design, Allen in running the business.Chapter 4 The Wide Pond

By 1910 the Union had proven itself. Alumni, faculty, and the University’s executive officers were on board. The new president, Harry Burns Hutchins, former dean of the Law School, was keenly interested in developing alumni support for the University as a whole; the Union was directly in line with that purpose. So the organization geared up to construct a headquarters that would dwarf Judge Cooley’s house.

To generate support for a new and much larger fund drive, the officers wanted preliminary drawings and renderings to show what such a building might be like. They tapped two architects — the brothers Irving and Allen Pond of Chicago — who were already connected to the Union plan by deep personal ties.

The Pond brothers were up-and-comers in Chicago’s Arts and Crafts school of architecture. So far, they were best known for the design of Chicago’s Hull House complex, where Jane Addams, a national leader in social reform, pioneered efforts to help and educate working-class immigrants. The Ponds also had designed notable residences in their hometown — Ann Arbor.

By coincidence, they had grown up in the house next to Judge Cooley’s residence on State Street. Their father had been publisher of the Ann Arbor Argus, a forerunner of the Ann Arbor News, and a member of the state legislature. Irving graduated from Michigan in 1879, Allen in 1880. Both studied under William LeBaron Jenney, a notable architect who split his time between Chicago and Ann Arbor. (Jenney’s distinctive design for the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity clubhouse, known as the “Shant,” still stands at 611 E. William Street.)

Allen stuck mainly to the business side of Pond & Pond. Irving was the chief designer. Chicagoans spoke of Allen as “the deep Pond,” and Irving as “the wide Pond,” presumably because he talked about so many interests and hobbies.

Tall and slender, with “dreamy poetic eyes,” Irving had been and remained a dedicated athlete. At White Stocking Park in Chicago, he scored the first touchdown in the first intercollegiate game played by the U-M football team, against Racine College on May 30, 1879. (Michigan won.) He prided himself on his skill as a gymnast and acrobat. He did gymnastic exercises every morning, and even in his 70s still startled friends by turning handsprings. He was a superfan of circuses, hanging out with circus people and joining circus organizations. He even performed as an acrobat. He read poetry and patronized the arts.

But Irving Pond’s chief absorption was architecture.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

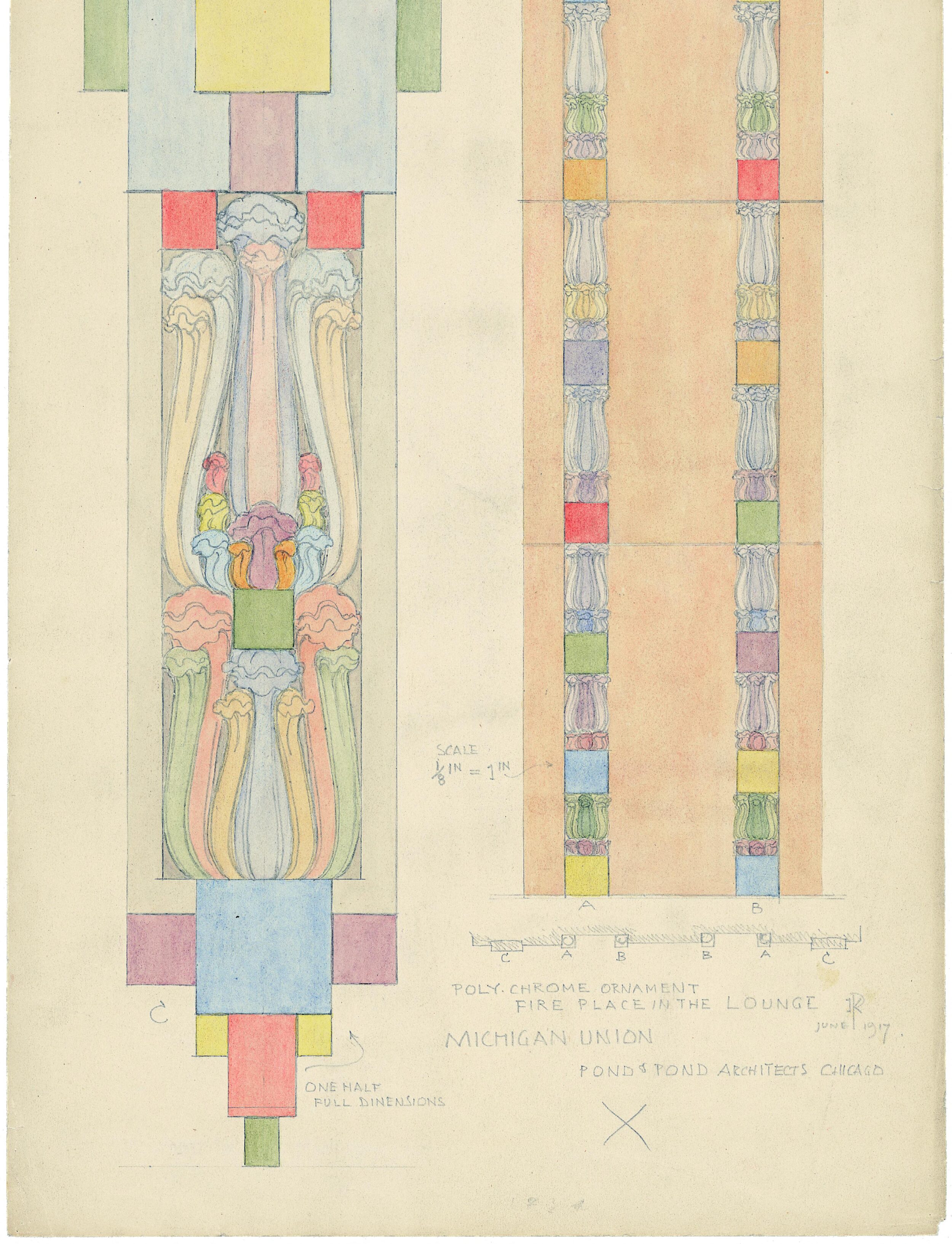

Irving Pond's 1917 design of ornamentation for the fireplace in the Michigan Union lounge. In his book The Meaning of Architecture (1918) Pond said of any architectural design that "the finished product, to those who can see and feel, should and will proclaim the spirituality of the creator."Image: Pond family papers, Bentley Historical LibraryChapter 5 “The Spirituality of the Creator”

“An Architect who truly is an Architect should be able to feel himself into his structure,” Pond would write later, “not only when it is in the process of creation but when the product is finished; and the finished product, to those who can see and feel, should and will proclaim the spirituality of the creator.”

So he hoped it would be with the Union. There is no question that he felt a spiritual connection to the building he imagined. He had grown up on its very site. He had succeeded on these grounds as a student and an athlete. To design a landmark building at his alma mater was a signal honor known to few architects, and he committed himself to the project with mind and heart.

His conception was enormous. On his drafting table, he sketched plans for a building 200 feet wide and 250 feet long, topped by a massive tower, bigger than any building devoted to student activities on an American campus.

He sketched a spacious lounge on the first floor, a main dining room to seat 150, and smaller dining rooms. He envisioned a banquet hall on the second floor big enough for hundreds of guests. This space would accommodate major social gatherings like the Junior Hop, typically held in gymnasiums or “places which do not always have a wholesome atmosphere.”

One floor up would be halls for billiards and pool; smaller game rooms; and meeting rooms for campus organizations, including the senior honor societies. On the fourth floor, to meet the needs of visiting alumni, there would be single rooms and dormitories for overnight stays.

For the basement Pond drew plans for the most enticing recreations — bowling lanes and a swimming pool. There would be space for offices, kitchens, and the power plant.

Pond designed the Union building in the style now called “Collegiate Gothic,” which borrows from the look of England’s Oxford and Cambridge universities but without so many architectural flourishes. He imagined interior spaces that would be elegant but not fancy, “more utilitarian than luxurious,” as one observer put it, with wood paneling and stone walls. In 1929, Pond was appalled to see stone gargoyles festooning the Lawyers Club, the first building to be constructed in the new Law Quad. “If ever I design in a style which requires such extraneous things to give it interest,” he remarked in a private letter, “I hope somebody will not only knock off the gargoyles but demolish the building itself. That is the way I feel about introducing extraneous matter into the work of art.”

Much of Pond’s tentative conception to promote the project would survive in his final design. He would shift rooms and functions and alter the configuration of spaces, but the essentials remained, with such pleasing additions as a barber shop and a library.

In 1911, Pond’s floor plans and artist’s renderings were published in the Michigan Alumnus and sent out to entice alumni interest and dollars. But first, alumni would have to know precisely what their checks would pay for.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Irving Pond's plan for the Union was larger than any comparable building in the U.S. Estimates of the cost quickly rose from $300,000 to $1 million, including $100,000 for furnishings and a $250,000 endowment for upkeep. U-M President Harry Burns put the first shovel in the ground on Commencement Day in 1916.Chapter 6 Saloon Kindergarten?

From the first days of Bob Parker’s campaign, President Angell had made the University’s position clear. He was all for it. So was the faculty. But the University was not going to pay for it, and neither was the state of Michigan. The new president, Harry Hutchins, took the same view. Planners estimated that the bill would come to at least a million dollars. Inevitably, the alumni would have to pay. So the alumni needed to be sold on the project.

But what was the project, precisely? Bob Parker and his student pals, even Professor Bates and his faculty allies, had always been a bit vague about the nature of this new beast. The planners would have to define it clearly, especially for older alumni who had graduated before the Union was organized.

So in the spring of 1911, an advisory committee of faculty and alumni convened to talk it through. In their discussion — saved in a transcript and preserved by the Alumni Association — they nailed down a concept that would answer nagging questions and frame the appeal to donors.

Of course, the campaigners would have to explain the original justifications, borne out by the Union’s performance so far. On these things the advisors agreed:

First, the Union exerted a leveling, “democratic” force. It was a setting where the one in five male students who belonged to fraternities were less inclined to lord it over the “independents” who couldn’t afford the fraternities’ fees. Among universities and colleges, Michigan was thought to have a student body less well-off than the average. Students without substantial means needed and deserved the sort of spaces for recreation that only the frat boys could afford. As Union members, all were equal.

The Union also promoted loyalty to the University as a whole, not to one’s department or class year. This alone was helping to diminish the long-standing outbreaks of hooliganism known as “rushes” — formal and informal competitions between classes and departments that often spilled into outright violence. And it appealed to President Hutchins, who wanted alumni of means to remember Michigan when it came to making charitable donations and writing their wills.

Finally, a Union building with fine spaces for recreation and relaxing would diminish the attraction of Ann Arbor’s saloons. National prohibition was several years off, but campaigns for it were running strong in Michigan. College boys were especially vulnerable to the lure of beer and booze. Wholesome alternatives were all to the good.

But many considered the Union a club, and that word invited trouble. It suggested the typical “men’s club,” with connotations of luxury and a hint of private vice. It certainly suggested drinking. The editor of the Ypsilanti Press no doubt spoke for skeptics across the state when he said the Michigan Union’s new quarters “will be viewed by many as a saloon kindergarten, and there ought not to be any imperative need for dignifying or multiplying bacchanalian opportunities.”

So the Union’s advisors doubled down. Though the University already prohibited liquor on campus, the campaign must state it clearly: No booze in the new Union.

The Union suggested the typical 'men’s club,' with connotations of luxury and a hint of private vice.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

For decades, the Union's billiards room was popular. When students' tastes changed, the room was often deserted, and eventually the space was converted to a study lounge.Chapter 8 The Plan Fulfilled

The alumni drive got the money needed, though it took a long time and a lot of arm-twistings.

By 1916, the Cooley house had been torn down to make way for construction. The Ponds’ childhood house was also acquired; it was moved to the back of the joined properties to serve as headquarters for the builders. Construction began, and Irving Pond’s design began to take shape on the ground.

Then, in April 1917, the United States joined Great Britain and France in the war against Germany. The campus went on a war footing. Construction stopped, and the partially built Union was put into service as quarters for the Student Army Training Corps.

After the war ended in late 1918, the Union looked to finish the job. But funds were now short, and the Alumni Association got tough.

In an act of astonishing high-handedness, they published a pamphlet titled “Unfinished Business: List of Alumni Who Have Subscribed Nothing.” There was no text, just a 180-page list of the names and addresses of each of the 18,000 living alumni (of some 30,000 in all) who had failed to contribute.

Then, finally, the building was complete. The doors opened in 1919.

The Michigan Union — the organization — had thrived throughout the years of fundraising and construction. Now its student officers came into their own. As the new building filled with students, the organization came to resemble the superstructure of a good-sized corporation.

There was a board of directors, a board of governors, a president, a general secretary, a recording secretary. Vice presidents presided over phalanxes of committees — the House Committee, Appointments Committee, Entertainment Committee (with six subcommittees), the Dance Committee. There were committees for the Freshman Mentor System, the Opera, and the Membership Campaign; for Publicity, Fall Reception and Art; for Billiards, Bowling and the Library. The board of governors had its own membership committee, and there were provisions for Select General Committees and Select Special Committees in case of special need.

The organization evolved and thrived for decades, still retaining its all-male membership. The Union planned and hosted countless events, meetings, lectures, receptions, dances, and dinners. And just as the founders had intended, the building became a thriving center of campus life and arguably the landmark that symbolized the University of Michigan more than any other. Major additions were built in the 1930s and 1950s. Remodeling occurred periodically, with a major refit in the late 1970s. A thoroughgoing renovation that took 20 months and $86 million was completed at the end of 2019.

The Women’s League grew in size and complexity and acquired its own spacious headquarters for women’s activities and organizations on North University Avenue. It opened in 1929. Like the “Michigan Union,” the words “Michigan League” signified both an organization and a building. That building, too, was designed by the Pond brothers; it resembles the Union in its architecture and interior style.

Famously, women were not supposed to enter the Union through the front door without a male escort. Instead, they were welcome through the side entrance, though not as members. The door restriction ended in the early 1950s. However, the all-male membership rule stayed in place until 1972.

But by then, the Union organization’s days were numbered. The University had long since recognized that student activities were part of its core business. Not long after women were admitted to membership, the University absorbed the Union into the vice president’s office for student services. A student-run University Activities Center took responsibility for many events the Union had hosted for decades. The Union and League buildings eventually were merged into the entity now called the University Unions, which also includes Pierpont Commons on North Campus.

The Pond brothers went on to design the student unions of Michigan State, the University of Kansas, and Purdue. Their style persists in recent construction at Michigan, too. Weill Hall (2006), North Quad (2010), and the Munger Graduate Residences (2015) all echo the look of the Union and League.

Irving Pond retained a fierce and possessive interest in the Michigan Union long after its doors opened. In the late 1920s, when planners made a minor structural alteration without consulting him, he complained to the dean of engineering, Herbert Sadler, who sat on the Union board.

“The building has a world-wide reputation for the harmony and distinctive character of its design,” Pond fumed. The alterations had “a commonplace factory effect not in harmony with the rest of the building… This is not right. Whoever is responsible for this is doing violence to all ethical and professional ideals. I can hardly realize that this is going on.”

Sadler’s response to Pond was polite. But when relating the incident to a friend, Regent James Murfin, Sadler said: “I sometimes wish that I had the artistic temperament because it must be a real satisfaction to feel that you are the only person in the world capable of doing a certain thing.”

The Union’s general manager, Paul Bulkley, was also miffed by Pond’s complaint. “I have always understood that this building made Pond’s reputation,” he remarked to Sadler, “not that Mr. Pond made the building’s reputation.”

In fact, both statements seem equally true.

Sources: Papers of the Michigan Union and papers of the Pond family, Bentley Historical Library; Michigan Alumnus; Michigan Daily Digital Archives; The University of Michigan: An Encyclopedic Survey (1941- ); Nancy Bartlett et al, “Constructing Gender: The Origins of Michigan’s Union and League”; Glenn Brown, Memories, 1860-1930 (1931); David Swan and Terry Tatum, eds., The Autobiography of Irving K. Pond (2009); Terrence J. McDonald, “The Pond Brothers and Democratic Architecture.” Additional research by Kim Clarke of the Heritage Project.

The building has a world-wide reputation for the harmony and distinctive character of its design.

– Irving K. Pond, architect