Depression Generation

By James Tobin

My generation learned to look at things as they were, not as they were supposed to be.– Edmund Love

-

Chapter 1 Hanging On

The Great Depression tore a hole in the University of Michigan. Thousands of students had to leave school. Thousands more who might have thrived at U-M never got the chance to try. In the “Roaring Twenties,” college had been a golden age of good times and great expectations. But the students who went to college in the 1930s lived in a realm of scarcity and fear.

The most detailed of the Ann Arbor memoirs from that era is Edmund Love’s. He was a Michigan-bred writer who published a series of autobiographical books in the postwar decades, including Hanging On: Or How to Live Through a Depression and Enjoy Life (1972). Love’s New York publisher attached a subtitle that made the book sound wry and playful. But Love’s story was hardly that. All but forgotten now, Hanging On and other memories of Ann Arbor in the ‘30s give us a glimpse of what truly “hard times” were like.

Of course, many students came from families that rode out the crisis in safety. But they, too, saw the Depression do its damage to friends. Even the most naïve came to realize they were living through a time of historic deprivation, and it shaped and seared them.

“My generation learned to look at things as they were, not as they were supposed to be,” Love wrote. “It became obvious that the old truths—such things as complete self-reliance and the childlike belief that virtue always triumphs—were not enough. . . .

“No one that I knew ever thought that things would stay bad forever,” Love wrote. Especially in the early years, from the stock market crash in November 1929 until the great wave of bank failures in 1933, “people talked about the upturn that would come the next spring. The next spring people would talk about the upturn that would come in the summer, and so on. The thing is that people really believed this. They had a blind faith in it. And because they did, they set up a pattern of living. It was called ‘hanging on.’”

That was how Love made it through Michigan. It took seven years.

“No one that I knew ever thought that things would stay bad forever.”

– Edmund Love -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Edmund Love as a high school senior in 1929.Image: Original image in Edmund Love papers, Bentley Historical Library.Chapter 2 “If You’re Going to School”

Ed Love was the oldest of three sons of a businessman who built up a lumber and coal operation in the industrial town of Flint, Michigan. In the 1920s there wasn’t a better city in America to do business, thanks to General Motors and the great auto boom, and the Loves’ fortunes soared. When Ed graduated from Flint Northern High in 1929, his gift for graduation was a new car, and when Ed asked his father if he was worth a million dollars, his father smiled and said yes, he supposed he was—though as Ed would learn, much of his father’s net worth existed only on Wall Street paper.

Love’s mother had been determined that her sons go to college. Just before she died when Ed was a boy, she made her husband promise to fulfill her wish, at least with one of the boys. So all through high school the family knew Ed was bound for Ann Arbor.

But Love’s father remarried early in 1929, and Ed’s new stepmother, Gladys, thought Ed needed seasoning at the Kemper Military School in Missouri. At seventeen, he spent a miserable year there, all but oblivious to the stock market crash and the family’s financial disaster. He came home in the spring of 1930 to find his car sold and his family deep in gloom. His father didn’t explain. But his grandfather took Ed aside to give the bare facts: Times were bad; everybody had to cut back. Still, there was no talk of Ed not going to Michigan—except from his stepmother, Gladys. Scared and anxious, she dropped ever broader hints that Ed should give up his college plans. Then one night she tried to lay down the law: Ed must not go.

If Mr. Love had been wavering, Glady’s dictum reminded him of his promise to Ed’s mother. The next morning he called Ed into his office, handed him a hundred dollars, and said: “If you’re going to school, you’ll need some new clothes.”

-

Chapter 3 Miracles

In 1930, Love wrote, “School started just before the real pinch of the Depression set in, so that the general tenor of college life that fall was more carefree than it might otherwise have been. It was closer in spirit to the twenties than it was to the thirties. The centers of campus social life were still the fraternities and sororities, and much emphasis was put upon good manners, good taste, and good living.”

He found a rooming house on South Division (this was before residence halls for men) and pledged a fraternity (Phi Kappa Sigma on Washtenaw). He cheered the football team; went to dances at the Union; studied for finals. He had hazy notions of becoming a writer someday, but otherwise he gave no particular thought to his future. It was enough simply to be at Michigan. The problem was how to stay there.

His father had sent him off with $300 in all—the last money he would ever give Ed. Basic costs for one semester were $49 for tuition; $80 to rent a room; $10 a week for two meals a day at the fraternity; $30 for books and fees. Those costs alone came to more than $300. “There wasn’t a day in that whole school year when I wasn’t financially strapped.”

Two minor miracles got him through the year. The first came when Ed was home for Christmas.

The previous summer, he had chanced to be the only witness to a train-versus-auto accident in which an auto passenger was injured. The passenger had sued the Pere Marquette Railroad for $50,000, and now Ed was to appear at the civil trial, scheduled for the first week of classes in January. Both sides thought Ed’s testimony would help their case. The plaintiff’s lawyer came and gave Ed $30 for expenses—travel to and from Ann Arbor plus lodging. Ed could hitch a ride and stay with his family, so that was pure profit. Then the railroad’s lawyer turned up and gave him another $30—also pure profit. He had to miss a whole week of school. Finally he testified for six hours. When the jury retired, the railroad attorney gave Ed $150 for his lost time; then the plaintiff’s attorney gave him another $150. The plaintiff won, and Ed had $360.

The second miracle was of Ed’s own making. It came in February, during Phi Kappa Sigma’s Hell Week—the week of sleeplessness and abuse from upperclassmen that led to initiation for first-year fraternity pledges. Early in the week, the brothers handed each of 28 pledges a gunnysack. Anyone who failed to come back with a black cat in his gunnysack by seven the next morning would be paddled—swatted on the rear with a hardwood implement roughly the size and shape of a cricket bat.

Ed reasoned, naturally enough, there wouldn’t be enough cats to go around. So he hitched a ride to Ypsilanti; found not just one black cat but three; got back to campus; and sold his extra cats for a dollar apiece. In the meantime he learned that other fraternities would enact the same black cat challenge in the next couple of nights, and he concocted a plan.

The next morning, his fellow pledges turned in a total of seventeen cats. The upperclassmen paddled the eleven who came up short and told the rest to dump their cats through a window of the neighboring Gamma Phi Beta sorority. Ed scurried over to the sorority, rounded up the cats, and sold them that night to the pledges at Sigma Xi. By the end of the week, he was up $39.

At the end of the school year, he owed $32 on his board bill. He paid it off that summer by driving a truck for his dad. He had one year under his belt.

* * *

The fall semester of 1931 approached. Ed knew there was no more money for school. He didn’t want his dad to have to say so. “It was a peculiar thing about my father and everyone else. . . . We were living in a world where all the people were broke, where everyone was struggling for survival, where forces beyond our understanding and remedy were operating on us, and still we were embarrassed to death at our predicament.” His father had made his mistakes with money, but the depth of the crisis—in Flint and around the world—was no one man’s doing. Yet Mr. Love blamed himself when he told Ed he couldn’t go back to school. “I think that his admission that he couldn’t fulfill my mother’s wish was one of the worst defeats he suffered.”

Construction in Flint had all but stopped. But people had to have coal. So the Loves scraped by. All that winter Ed delivered coal to people in cold houses, many of them far worse off than the Loves.

“There wasn’t a day in that whole school year when I wasn’t financially strapped.”

– Edmund Love -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

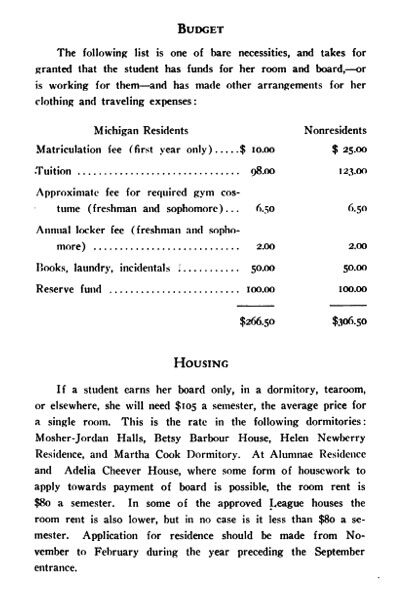

The Office of the Dean of Women published this estimate of the typical U-M woman student’s costs in the early 1930s.Chapter 4 A Crooked House

It had taken only one Depression winter to shatter Ed’s stepmother, Gladys. When Ed came home from military school he had found a different woman from the charming, elegant socialite he had known. Her hair had turned gray. She was “thoroughly frightened” and “penurious to the point of insanity.” She would sit with the Flint Journal, scouring the ads for the lowest grocery prices, then make the boys burn gasoline to drive her from one end of town to the other to save pennies here and there. She “threw tantrums if any of us so much as talked about going to the movies.”

In the end Ed came to think “Glad was good for all of us, because we never spent a dime without thinking what she would say when she found out. We needed some restraint.

“The one important thing to remember about our family and most other families of the time was that the Depression welded us into tight-knit little groups. In spite of the bickering, it would never have occurred to any of us to act outside the interests of the family. I was nineteen in the fall of 1931 and the thought of leaving home and going out on my own had never occurred to me. It wasn’t simply a question of having no ambitions. I knew that my father needed my help and at the moment all our interests were centered in the need to keep the lumberyard going, for our livelihood was there. When the decision was made that I wouldn’t go back to school it was a foregone conclusion that I would work for my father. There was no discussion of it at all.”

* * *

No one welcomed the Depression just to have a tighter family. But the closer ties that Love noticed at home were felt in many families with students at Michigan. That, at least, was the conclusion of Robert Cooley Angell, a U-M sociologist (and grandson of U-M President James Burrill Angell) who made a thorough survey of U-M families in the early ‘30s. Entitled The Family Encounters the Depression, Angell’s book reported in detail on how 50 families coped with a significant drop in income. “Most of these families,” he wrote, “came through with flying colors.”

One such family lived in Ann Arbor with three children at U-M, though the father had lost his job as an engineer and had to pick up work as a day laborer, with a drop in income from $4,400 to $600 a year. They put their house up for rent and moved into a three-room apartment; the children got “board jobs” to cover their meals. “The children have realized that it is up to them to help the family through its difficulties and have all pitched in with a will. . . Because of necessity they share each other’s possessions, and their petty jealousies have vanished. The family really does seem to be happier, at least as far as its internal relations go, than before. They go around together much more and find delight in each other’s companionship.”

Families that fell from loftier heights may have fared worse. Angell reported on a mother and father, both from wealthy and aristocratic Chicago families, who lost nearly everything they had. The father became “dictatorial,” the mother “a thoroughbred with a broken spirit.” When a daughter, Laura, announced her plan to put the proceeds of a summer job into her education, “her father demanded that she turn it all in for family expenses. She refused, and left for the University of Michigan where she obtained a board and room job doing housework. This enraged her parents who felt that she was smudging the family escutcheon by ‘demeaning herself’ to do housework for someone else. Since then she has been completely self-supporting and has not returned home… Laura is much happier than she has ever been and finds her newfound freedom wonderful.”

* * *

One morning Ed’s father went out and stared at the great pile of scrap lumber that rose three stories high—the cast-off ends of two-by-fours and warped sheets of plywood that every lumber yard accumulates. Back in his office, Mr. Love pulled out an old book of house plans, then made a few phone calls. He told the boys to go out to the scrap pile and pull out every salvageable piece of wood they could find. He sent Ed’s brother to the homes of anyone who owed the Loves money. With the trickle of cash, Mr. Love bought cement.

Then, over the next few months, on a foreclosed lot in an exclusive neighborhood, Mr. Love and his men assembled the strangest house in Flint—“the crooked house,” the family called it. “It looked more like a shack than a shack did,” Love said. “There were narrow boards and wide boards, dirty boards and clean boards. It was a rare room which had two window holes the same size. . . . Two rooms had oak floors, three rooms had maple floors, and two had knotty-pine floors.”

As the crooked house rose that summer, Ed picked up work laying a few cement driveways. One morning it rained, so he bummed a ride to Detroit. The Tigers were rained out. So Ed hopped the ferry to Windsor, Ontario, where he stumbled into the local horse track. He had never been to a race. He had seven dollars in his pocket—his whole estate. He asked how to place a bet and risked two dollars, the minimum. A couple of hours later he was up $97.

That night, back in Flint, he calculated the cost of another semester in Ann Arbor. Tuition, books and room would cost $124. If he could find a board job, he could eat. His father told him to get back to Ann Arbor—they’d find the rest somehow.

-

Chapter 5 Sunny

In the fall of 1932, Love wrote, “the Ann Arbor that I went back to was like a ghost town. The Depression had taken an alarming toll. . . Of the twenty-eight pledges who had been initiated with me, only six were still in school . . . Seventy fellows had eaten in our dining room during my first year. Now there were only thirty-two. All the campus gathering places had closed.”

Yet there was a curious fact about the Great Depression in a college town like Ann Arbor. On the average day, privation was private, known only to the students going through it and perhaps their closest friends. On the surface, things seemed unchanged. Many students with hardly an extra quarter lived in beautiful buildings. “No matter how broke I was,” Love wrote, “I spent that fall in a very posh atmosphere. Our house . . . sat on a huge plot of land on Washtenaw Avenue . . . and it had sweeping lawns, front and rear, with a stand of great trees surrounding it. The house itself had four floors, luxuriously furnished [with] a spacious living room, cardrooms, and guest suites.” Small savings here and there—going Dutch, for instance—allowed many strapped students to keep up a social life, and they borrowed clothes and burrowed in trunks to pull off the appearance of stylishness. “Paradoxically the Depression was a period of great elegance,” Love wrote. “Girls had taken to wearing long dresses that swept the floor and most of them did their hair up in elaborate coiffures.”

If your family had been poor to begin with, the Depression was something that happened to other people. “I had as much in worldly goods as I ever had, which was slightly more than nothing,” remembered Francis “Whitey” Wistert, an All-American tackle for the Wolverines. He was the son of a Chicago policeman killed by a holdup man when Wistert was fifteen. “With a room-and-board job on campus and factory employment during the summer, I was as well off as many of the student body and better off than some.”

And if your parents were comfortable and their livelihood was untouched, college might go on as if nothing at all had gone wrong.

That was how it was for a Pennsylvania girl named Helen Loomis. Her good cheer led her new friends in Ann Arbor to call her “Sunny.” She was the third of four daughters in an affluent family in Wilkinsburg, a suburb of Pittsburgh. In September 1931 she moved into 435 Mosher Hall. (Her steady letter-writing would produce a file of hundreds of letters, now preserved at U-M’s Bentley Historical Library.) Her family was close—“I don’t think there are very many families who are as happy as ours and who have as much in common,” she wrote—but if she was homesick, she didn’t say so. Her new life was a happy routine of classes, studies, sorority teas and dates. The worst behavior she saw was when five Mosher girls stuffed the mail chute with toilet paper—“Am I glad I wasn’t one of the girls. . .”—and her greatest anxiety was which sorority would give her a bid.

September 29, 1931: “I’ve been to so many teas and dinners this past week that it’s a wonder my clothes even fit me. So many sweets isn’t any too good for the schoolgirl figure.”

October 5, 1931: “I’m thrilled through and through because I just received word that I’m to be pledged to Chi Omega tomorrow night. . . I’m so happy because I like them so much and was so afraid I wouldn’t make it.”

November 17, 1931: “I’m all thrilled. I’m going to two formals next weekend. Friday night I’m going with Harold to his frat (Sigma Phi) and Saturday night with Joe to his (Sigma Zeta) formal. That’s the night of our biggest game (Minnesota)… I know I’ll have a marvelous time both places.”

Sunny’s father was assistant general manager of Union Switch & Signal, a big Pittsburgh firm that made equipment for the railroads. So Helen received a regular check for clothes, movies and sundries.

“Thanks a million times for the check, Daddy,” she would write. “It certainly is wonderful to be able to have $30 a month roll in but I wish I could earn part of my way through school at least.” She didn’t.

Her first two years in Ann Arbor, from fall 1931 to spring 1933, were the worst of the Depression. But in her letters there is scarcely a word about the national crisis. On the eve of the presidential election of 1932, when Franklin Roosevelt swept Herbert Hoover out of office, Helen’s only remark on politics was a brief aside in her report on the big Panhellenic Banquet at the League:

“It was very lovely. We had fruit cup, cream chicken in patty shells, shoe string potatoes, fresh peas, cabbage jello salad, hot rolls, ice cream molded inside of cake, and coffee. There were several very good speakers and it was quite evident for whom they were going to vote. The main speaker of the evening was for Roosevelt. I think Hoover will get the win but he’s going to have to work for it.”

Hoover did not get the win, of course, but Helen’s letters pass over that news. Apparently her parents were Republicans.

The boy she really liked was that Sigma Phi, Harold Gehring. He was from Grand Rapids. He was a senior the year Helen was a freshman.

“He’s a marvelous dancer and I certainly was scared to dance with him,” she told her parents. “The first two pieces were slow and we got along fine . . . and then the orchestra started one of those terribly fast pieces and he said, ‘Well, this will tell the story,’ and my heart just sank. Well, it just seems as though some little spirit told me where to go because we just sailed.”

They saw more and more of each other. She learned his parents were dead, and that he wanted to be a doctor. “Harold and I had quite a talk yesterday. I didn’t know any boys in this generation had such good common sense.”

It wasn’t until spring, when he was accepted by U-M’s Medical School, that he disclosed his financial troubles. She had not wanted to ask, but she and her parents had speculated, and “as we guessed he was hit pretty hard by the depression.” He had inherited some property from his parents but the value had collapsed. “In 1929 when he came to school he was on easy street but not so now.” He was washing dishes at his fraternity to help pay his way.

He found the means to enter medical school, and soon it was obvious that he and Sunny Loomis were a love match. “It would be useless to start to tell you what I really think of him,” she wrote her parents. “Anyway he’s just as wonderful as you think he is and then some. . . [He] is working awfully hard but he loves it and I love to hear him tell about cutting this and that out of his corpse.”

Her letters began to reflect a growing maturity. By the middle of her sophomore year she was no longer the starry-eyed sorority pledge but a thoughtful young woman contemplating her future. Her plans to major in English were giving way to a serious interest in biology. Through Harold’s eyes she was seeing a wider world. When he went to Detroit to search the pawn shops for an inexpensive microscope, she went along. No luck, she said: “I guess the doctors haven’t gone that broke as yet.”

On the average day, privation was private, known only to the students going through it and perhaps their closest friends.

-

Chapter 6 The Counter Man

In January 1933 Ed Love’s father put the crooked house on the market. The same day a GM executive bought it for $9,300. Mr. Love purchased five train-carloads of lumber and ten carloads of coal, then handed Ed a check for $500.

But in the following weeks, starting in Detroit, banks began to fail. The day after Franklin Roosevelt took the oath as president, he declared a week-long “Bank Holiday”—breathing room for a desperate effort to save the financial system. Some banks survived. Many never reopened. The Loves’ bank went down, carrying Ed’s $500 with it. He and his father didn’t even talk about it. Ed went down to Ann Arbor to pick up his clothes, then came back and got back behind the wheel of his old coal truck.

* * *

Love was the first to acknowledge the role that sheer luck played in his career at Michigan. Without his profits in black cats or his night at the Windsor racecourse, he might have been lost to U-M for good. Many another student scratched and skimped as hard as Love did. But luck overlooked them, and they never made it through.

One of the unlucky ones worked the counter at the Calkins Fletcher Drug Store, two doors north of Nickels Arcade on South State. His name was Ernie. He was from Niles, a small town in southwestern Michigan, where his father, too, manned a drug store counter. Ernie made short-order sandwiches, polished the brass and steel soda fountain, worked the register. Late at night he would chew the rag with Richard Lardner Tobin, another Niles boy who had known Ernie since high school. Dick Tobin and Ernie had started at U-M the same year. But Tobin’s father owned the newspaper in Niles, so he could support his son through college, while Ernie’s father could spare only a few dollars for his son, and only now and then. So when Tobin was getting ready to graduate in 1932, Ernie was two years behind.

Writing long afterward, Tobin said: “I never saw Ernie without remembering the feeling in the pit of my stomach one night my freshman year when half a sorority came down with fur coats over their pajamas, insisted on being served at five minutes of midnight (when the store closed), and left an hour later after being careful to fix a nickel or two in tips in the residue of marshmallow, bittersweet, and butterscotch. The drained face of the counter man had tightened perceptibly as he surveyed the sticky counter, its nauseating contents, and each residual soda glass exposing the few precious pieces of silver.”

Ernie got skinnier in Ann Arbor but he never had to go hungry, Tobin said. “That was one advantage of being nighttime counter man . . . the bits of sandwich filling and edges of bread and toasted roll, sheafs of uneaten dill pickle, droppings of soft butter, shreds of brown lettuce…”

Tobin graduated. With his Michigan diploma and his experience at the Michigan Daily, he got a job as a reporter. He became a war correspondent, a prominent essayist, and eventually managing editor of Saturday Review.

He never knew what happened to Ernie until one day when he was back in Niles to visit his family. He stopped in at Richter’s City Drug and Book Store, where, as a boy, he had always seen Ernie’s dad behind the counter. At first he thought it was Ernie’s dad he saw now.

“Then suddenly it was young Ernie, not his father, I was seeing, his hair grayer than it had a right to be at his age, hair to match the color of a drawn face, the same nervous energy exploding from every fiber of a thin frame. He did not see me at first, but when he did he let out a yell that startled me, and he ran over to grasp my hand. . .

“I sat down just as I had in Calkins Fletcher’s practically every night for four years, watching fascinated as expert fingers crumbled the raw hamburger papers and were then wiped automatically on the dirty apron as they had been wiped so many times at Ann Arbor . . .

“When it came time to pay Ernie waved my dollar aside.

“’On the house, guy, on the house,’ he said triumphantly. ‘I don’t own this place, not yet. But Mr. Richter is going to let me buy in some day, he told me so, as soon as I finish the pharmaceutical course. I study Sundays and nights after work. By mail. Never did get the degree, of course. I stayed seven years, they didn’t let me finish. But I’m going to have a shingle on that wall over there one of these days. You wait and see. I wish Pop hadn’t died so young. He’d have been proud to see it, when it comes. . .’”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

State Street in the 1930s. Calkins-Fletcher Drug Store is at right.

-

-

Chapter 7 “A New Shadow on the Earth”

By one stratagem and another, Ed Love tallied more semesters on his transcript. For a year he stacked fenders in Flint’s sprawling Buick plant. At a fraternity craps table he wound up the night with $167. (Actually, a brother snuck out with Love’s roll at the height of his hot streak; he gave it back the next morning, saying: “If I hadn’t taken it, you’d have put every cent of it back in the game.”) The unexpected sale of a few swampy acres in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, left to Love and his brothers by their grandfather Love, brought him $165 on the eve of the fall semester of 1934—and again he was back in Ann Arbor. A year later he scored $586 in a chain letter scam—more money for tuition.

That was the year Ed conceived the idea that he would simultaneously erase his money troubles and assure his future by winning a Hopwood Award for a major work of fiction. He had never written so much as a short story.

* * *

Just before Edmund Love first entered U-M, the will of Avery Hopwood, a Michigan graduate who died in 1928 after making a small fortune writing comedies for Broadway, established what soon became the most prestigious student literary prizes in the U.S. Love saw the awards listed in a booklet of U-M scholarships—$1,500 for the top prize. He thought of a story he had been fooling around with—an adventure tale about the Ottawa chief Pontiac’s rebellion against the British. This would be his “major work of fiction.” But to enter the Hopwood competition, he would have to take a course in English or journalism. He went to see Erich Walter, an instructor in English and assistant dean of students. Love later decided Erich Walter was “the kindest, gentlest man who ever entered my life.” He had no writing credentials. But after a 10-minute talk, Walter let him into English 153, Creative Writing.

Ed set himself a strict regimen and followed it, pounding on an old typewriter every night from 11 p.m. until 2 a.m. “I was a man obsessed.” In class he found himself surrounded by an “arty-arty” collection of “would-be novelists, poets, and playwrights.” There was a lot of talk about James Joyce and Henrik Ibsen. “I didn’t aspire to anything more significant than The Saturday Evening Post myself, and a good deal of what went on in that class went right over my head.

“There was one pretty good writer in there, however. His name was Arthur Miller. I remember that he impressed me favorably at the time, not because of what he wrote, but because he seemed to be the only sane member of the group.”

* * *

Arthur Miller had come to Michigan because it did not restrict the admission of Jews, unlike Columbia, Yale, and other members of the Ivy League; because tuition was low; and because of the Hopwood Awards. Like Ed Love, he was the son of a successful businessman who had lost most of what he had. Like Love’s stepmother, Miller’s mother had turned bitter. And like Love, Miller had helped out in his father’s struggling business, carrying samples for one of his father’s salesmen, a broken man whom playgoers would one day meet in the character of Willy Loman. Miller had worked for two years in a warehouse to save $500 for a year at Michigan.

When he got to Ann Arbor, Miller wrote later, “I felt at home. . . It was a little world, and it was man-sized. My friends were the sons of die makers, farmers, ranchers, bankers, lawyers, doctors, clothing workers and unemployed relief recipients. They came from every part of the country and brought all their prejudices and special wisdom. It was always so wonderful to get up in the morning.”

Like Ed Love, too, Miller threw himself at the goal of winning a Hopwood. As a sophomore he labored on his first play, about a father and two sons in the midst of a labor strike. He was washing dishes to earn his board and and feeding the mice in a U-M lab off campus. He lived on North State with a family named Doll. A son Miller’s age, Jim Doll, was a graduate student in theater; they became friends, and Doll helped Miller with the fundamentals of drama. Miller stayed in town over the spring break, when there was more time to write. The Hopwood deadline was looming.

“Working day and night with a few hours of exhausted sleep sprinkled through the week, I finished the play in five days and gave it to Jim to read. I was close to despair that he might make nothing of it, but I had never known such exhilaration—it was as though I had levitated and left the world below. . .”

Finally Jim Doll emerged from his room with a smile. “It’s a play, all right,” he said. “It really is!… I think it’s the best student play I’ve ever read.”

“Outside, [Miller would write,] Ann Arbor was empty still in the spell of spring vacation. I wanted to walk in the night, but it was impossible to keep from trotting. . . . I ran uphill to the deserted center of town, across the Law Quadrangle and down North University, my head in the stars. I had made Jim laugh and look at me as he never had before. The magical force of making marks on a piece of paper and reaching into another human being, making him see what I had seen and feel my feelings—I had made a new shadow on the earth.”

* * *

Love was bringing his own manuscript to a close. “I wasn’t a good writer, of course. I was a terrible writer and my novel was a terrible novel. Dean Walter knew how awful it was, but being a kindly man, he never found the words to disillusion me. I missed his hints completely.” He finished just before the deadline for submissions—4 p.m. on April 22, 1935. He heard that one of the judges of the novel competition was Sinclair Lewis, the author of Babbitt and Arrowsmith who would win the Nobel Prize for fiction.

The awards ceremony was held on the last Friday in May in the Union ballroom. The names of the award-winners were announced, Arthur Miller among them. There was no mention of Love. He turned away.

Then he saw Erich Walter beckoning to him. They crossed State and went up to Walter’s office in Angell Hall. There, Walter pulled out Love’s stack of pages and looked at the despondent student.

“The judges didn’t care much for this,” he said. “Mr. Sinclair Lewis said it was one of the worst novels he ever read.

“ I suppose it’s cruel for me to tell you this at this particular moment. I’m well aware of how much you wanted to win one of those prizes. I have a reason. You’re going to have to learn to shrug off adverse criticism. I had more than fifty students in my classes this year. Some of them got prizes, but I doubt that any of them will be writers—except for Arthur Miller. I could have brought Arthur back here, but he doesn’t need encouragement. You do, because you are going to be a writer, my friend. No matter what black moments the future brings, don’t you ever forget it, and don’t ever give up.”

Recalling that day some thirty years later, Love said: “That was the big moment in my life. … For the first time in my life, I knew what I wanted to be—was going to be.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Edmund Love in the Pacific during World War II.Image: Original image in Edmund Love papers, Bentley Historical Library.Chapter 8 Epilogue

Arthur Miller became one of the most celebrated American playwrights of the 20th century. For Death of a Salesman, he won the Pulitzer Prize. The Arthur Miller Theater in Michigan’s Walgreen Drama Center was dedicated in 2007.

Helen “Sunny” Loomis graduated from Michigan in 1935 and married her Sigma Phi sweetheart, Harold Gehring, who became an orthopedist. In 1938 she earned a master’s degree in bacteriology; she held a research fellowship at U-M from 1935 to 1941. During World War II, with many medical personnel serving in the armed forces, the Gehrings volunteered their time to give free medical care to Native Americans in upstate Michigan. Dr. Gehring died in 1984 after a long and distinguished career, much of it spent at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Michigan. After his death, Helen endowed the Harold W. and Helen L. Gehring Professorship in Orthopaedic Surgery at the Medical School.

* * *

When Edmund Love had his chat with Dean Erich Walter in April 1935, he needed only one more semester to graduate. But his luck seemed to run out. All that summer he scratched for dimes. Labor Day approached, but he had nowhere near enough money for that final term.

Then, just before Labor Day, a friend at G.M. found him a job at Fisher Body #1, where the workers made bodies for Buicks. If he worked in Flint just one more semester, he could go back to Ann Arbor and finish. His title was payroll coordinator. His job was to enforce the “speedup,” management’s system for extracting more work for less pay. By January he lost his stomach for it, spoke his mind to his boss, and was fired.

His conscience had terrible timing. He’d just blown most of his savings on white tie and tails for his brother’s wedding and a refrigerator for a wedding present. (At the wedding, 50 Fisher Body workers sat in back and raised a cheer for Ed when, as best man, he strode out of the church.)

One last stratagem ensued, this one provided by the University itself. Raleigh Schorling, dean of the School of Education, had cooked up a plan for aspiring teachers who were close to graduation but short of funds. With one semester of intensive training, followed by summer school, then six weeks of practice teaching in his home town, a student could complete his degree and gain a teaching certificate. With just enough cash to get through the intensive stretch, Ed took a chance and enrolled. At the end of the spring semester, Leroy Pratt, Flint’s assistant superintendent of schools, offered him a teaching contract for the coming fall.

Love signed it without even reading it. Then he admitted to Pratt that he was still short of the tuition he needed for summer school.

“Hell, that ought not be any problem,” Pratt said. “Ernest Potter is the president of the bank, and he’s also president of the school board. Why don’t you go see him in the morning and ask him if he’ll lend you the money?”

“I went and I walked out of the bank with three hundred dollars,” Love wrote. “I was home free.”

In August 1936 he went to the University Registrar’s office to collect a piece of paper attesting that he had earned a degree as Bachelor of Arts. His diploma came in the mail two months later. “It wasn’t much of a commencement,” he wrote, “and in later years I never knew just which class I belonged to. At the moment I didn’t care about any of it. I was convinced that I was about to begin life.”

* * *

Love taught in the Flint schools for four years. He decided that when the Depression was over, he would buy his first new car—his first, that is, since the one his father gave him when he graduated from high school in 1929, then had to sell. In October 1940 he decided the time had come. He picked up his new car and drove it directly downtown to register for the draft. He spent World War II as an Army officer in the Pacific theater.

After the war he began a writing career that would lead to the publication of twenty books, most of them autobiographical, including Subways Are For Sleeping (1957) an unlikely hit about Love’s perilous bout with poverty as a homeless writer in New York; War Is a Private Affair (1959); The Situation in Flushing (1965), an account of Love’s small-town boyhood; and Hanging On. He died in 1990 at the age of 78.

Sources included Hanging On: Or How to Get Through a Depression And Enjoy Life, by Edmund Love; the papers of Helen Loomis Gehring, Bentley Historical Library; “An Oat a Day” by Richard L. Tobin and “The Lines Between the Lines” by Arthur Miller, in Our Michigan by Erich Walter; The Family Encounters the Depression by Robert Cooley Angell; Timebends: A Life, by Arthur Miller; and “University of Michigan” by Arthur Miller, Holiday Magazine (1953.)