A Cabin in the Woods

By Kim Clarke

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Allow this place to be your haven.– U-M Biological Station student

-

Chapter 1 Leaving a Mark

When his career of nearly 50 years came to an end, Lou Revere Crandall could take credit for managing the construction of monumental and iconic buildings throughout North America.

There was the U.S. Supreme Court Building and the National Archives in Washington. The Time-Life Building in New York. State capitols and post offices, churches and hospitals. The Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center. The National Hotel of Cuba in Havana. Structures on the campuses of Yale, Harvard and Cornell. And the gleaming United Nations Secretariat Building along Manhattan’s East River.

Crandall signed off on all of them as the longtime president of the George A. Fuller Company, one of the country’s most prominent construction firms.

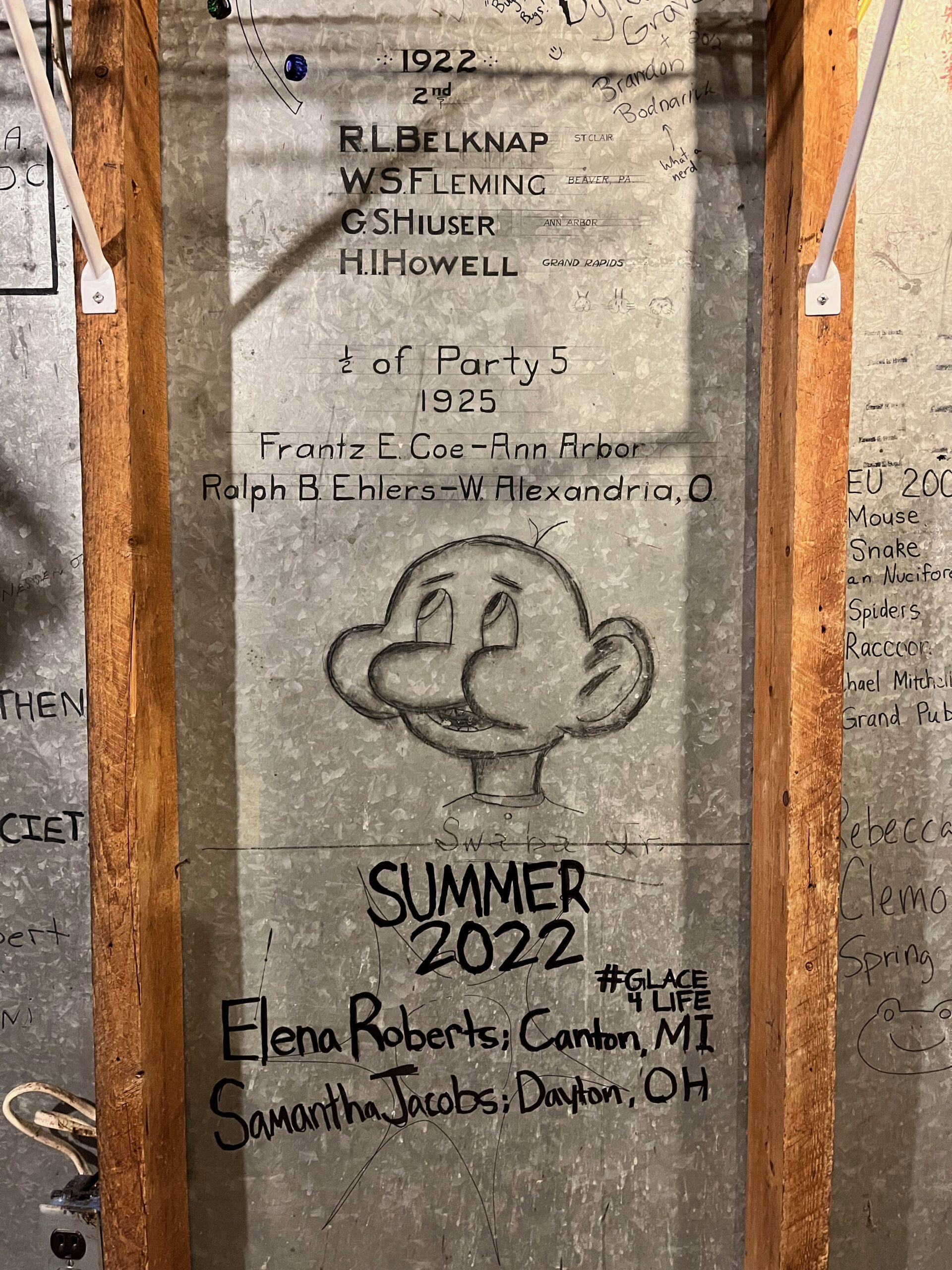

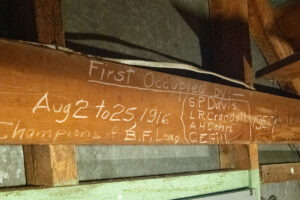

But the building Crandall first affixed his name to sits deep in the woods of northern Michigan where, in 1916, he carved his initials into the pine beam of a newly constructed cabin for Michigan students. An engineering senior from Toledo, Crandall and three cabinmates from the Class of 1917 let the world know they were the first occupants of the little steel-clad shack.

For more than a century, Michigan students have been leaving their mark on the gray metal cabins at the U-M Biological Station. They have blanketed the interior walls with names, poems, inspirational messages, song lyrics, and drawings of the natural world surrounding them.

The graffiti serves as a rustic time capsule of a unique summertime experience many students say changed their lives and set the course for their careers in science and the environment.

“It’s hard to believe that 4 weeks could reshape and void 19 years,” a student confessed on a cabin wall in 2011, “but I’ve never heard my soul speak to me so clearly as it did here …”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

No sooner had a cabin opened in 1916 than students recorded their names for posterity.Image: Daryl Marshke, Michigan Photography

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Bug Station campers in 1919 stayed in canvas tents.Image: Gertrude Celeste Benson scrapbook, Bentley Historical LibraryChapter 2 On Camps and Campers

The history of the U-M Biological Station intertwines with Camp Davis, which began as a summer camp for engineering students.

Camp Davis came first, in 1874, and moved from location to location throughout the state for summer sessions. Finally, in 1908, the camp made its permanent home on 1,441 acres along the south shore of Cheboygan County’s Douglas Lake, some 20 miles from the tip of the Lower Peninsula.

The area was ideal for aspiring civil engineers to practice their trade. Lumber companies had stripped the land of old-growth white and Norway pines, beech, oak and maple. Underbrush and woody debris created by logging fueled fires that blackened the earth. The area was a wasteland. But the ugly clearings were perfect for surveying and topographic work.

The region also presented hands-on opportunities for students to explore botany, biology, zoology and other aspects of the natural world. The land was renewing itself after the reign of the timber barons; birds, trees, animals and amphibians were returning. It was ripe for a field biology station.

“Any botanist finds interest in noting the effect of lumbering and fire on the forest vegetation,” said Professor Henry A. Gleason, “and soon becomes an ardent conservationist, if he was not one before.”

The University established the Biological Station in 1909, directly alongside the eastern edge of Camp Davis on the shore of South Fishtail Bay. For two decades, the camps co-existed; at times, students shared a mess hall. But by 1929, Camp Davis needed new surroundings. Aspens and second-growth pines now soared overhead, blocking sight lines for surveyors. The engineers abandoned their camp for Wyoming, and the biologists moved in.

New roads went down. A dining hall and two laboratory buildings went up. Some 100 buildings were either moved or shifted (pulled on skids by horses), doubling the size of the Biological Station. Water and sewer lines snaked through the enlarged camp, which the University could claim as the largest freshwater biological station in the world.

Amidst the new construction and relocated buildings sat the steel cabin where Lou Crandall scratched his name, along with dozens more of the rustic buildings first occupied by engineering students and now the summertime homes for biologists.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Camp Davis student Hsien Kwei Kuo, of Shanghai, with his surveying transit in 1916.Image: U-M Engineering Communications & Marketing records, Bentley Historical Library -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Surveying transits were essential to the Camp Davis experience.Image: Daryl Marshke, Michigan Photography

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Building a cabin at Camp Davis in 1916.Image: U-M Engineering Communications & Marketing records, Bentley Historical LibraryChapter 3 Engineering a Home

The steel cabin walls that would be a Station trademark were fabricated by workers at the campus metal shop in Ann Arbor and placed on train cars, stamped with a delivery address: Charles Jarman, University of Michigan Surveying Department, Pellston, Mich. Jarman was the on-site caretaker for both the Biological Station and Camp Davis, and his stenciled name remains visible on numerous cabins.

The erection of steel cabins was a welcome change for campers. Canvas tents trapped heat and offered little air movement. The wooden floors had cracks that served as entryways for insects; students slept under mosquito netting. The new tin cabins, with poured concrete and lake sand foundations, were tighter. They stayed cooler during the day and kept out the rain. And the sound of raindrops hitting the metal roofs could be hypnotizing.

Engineering students assembled the first five cabins in 1914. Another eight went up in 1915, followed by 17 more a year later.

Teaching assistant Wesley Bintz supervised six engineering undergraduates during the 1916 building spree that led to Lou Crandall’s new summer residence. “They were largely inexperienced. Within two weeks they were working to good advantage,” said Clarence T. Johnston, director of Camp Davis.

Bintz and his crew doubled the number of camp cabins that summer. He then prepared detailed blueprints “so that at any time, under new hands, work may proceed and profit by past experience.” His meticulous drawings and directions reflected the civil engineering degree he had earned earlier that year. (“Set the transit at E, sight at F, turn 90° and drive a small nail on the batter board at A’, plunge, set nail on batter board at D’. Stretch a string between these points.”)

Between the cost of supplies and wages paid to student laborers, Bintz estimated each cabin carried a price tag of $111.93. Many were painted white by summer’s end.

Today the grounds of the Biological Station are dotted with nearly 50 one-room rustic cabins like those that Bintz helped to build. They are uninsulated, with open rafters and small windows that look out at neighboring cabins and pines. Each has two or three single beds along with a wood-burning stove. Toilets and showers are in communal buildings.

The University opened its first residence halls – Helen Newberry and Martha Cook – in 1915. With the quintet of northern Michigan rustic cabins that rose in 1914, one could argue that the Biological Station is home to U-M’s first and oldest form of student housing.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Alumnus Joel Heinen, who teaches at Florida International University, was a visiting professor at Bug Camp from 1993-2017.Image: Daryl Marshke, Michigan PhotographyChapter 4 Bug Camp

Preparing to set up the new Biological Station adjacent to the engineers at Camp Davis in 1909, Director Jacob E. Reighard encountered what every camper since has faced: bugs.

For five days they swarmed, “a pest of black flies so severe that the members of the Engineering staff … were disabled and driven from the camp,” Reighard said. A graduate student, Cora D. Reeves, made it her summer’s research work to determine how to destroy black fly larvae.

To no avail. In 1983, camper Laura Rood studied entomology and was “tormented by the black flies and their drill-like incisions into our skin.”

Researchers move in and move on, but the insects are permanent residents.

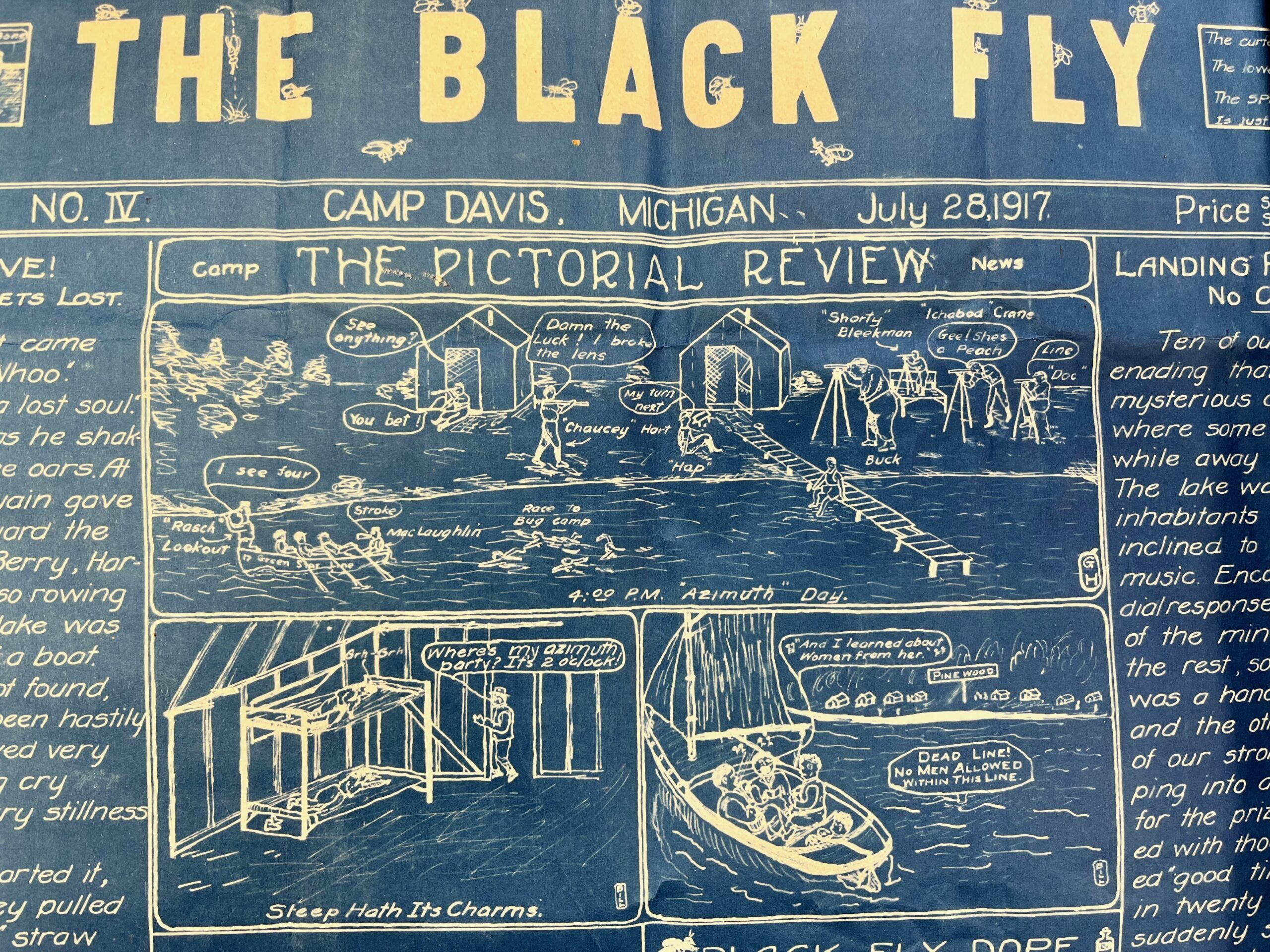

The place has always been Bug Camp. Early students played on baseball teams sorted into the Black Fly and Mosquito Leagues; Lou Crandall and his pals memorialized their Black League championship with a rafter carving. Later softball players christened themselves the Leeches (because they sucked). Students printed and delivered camp news via The Black Fly. And, of course, insects of all manner have been the focus of students’ research and fieldwork.

Campers’ drawings of bugs adorn cabin walls. Butterflies, beetles, mosquitoes, grasshoppers, dragonflies, and moths have made their way into the cabins through students’ artistic expressions, and there they remain. (Joining them are hand-drawn porcupines, flowers, squirrels, fish, and a critter named Twitch – “best chipmunk ever!”)

Herbert B. Hungerford was an entomology professor from the University of Kansas who taught and conducted research for nearly 30 summers at the Biological Station. He rhapsodized about the multi-legged creatures he studied:

Slip out to your cabin

And, in quiet, retire

To be lulled by the crickets

And the katydids’ choir.

In 2019 – 110 years after Jacob Reighard wrote of the black fly swarm – a camper named Emily scribbled a reassuring message to newcomers: “The bugs aren’t as bad as they seem.”

-

Chapter 5 “Happy and Productive Summers”

In the summer of 1937, Thomas Weller headed north for Bug Camp.

Weller was born to be a doctor – the same profession practiced by his father, uncle and grandfather. Growing up in Ann Arbor’s Burns Park, he joined his father, Carl, on the U-M campus, where the elder Weller chaired the Department of Pathology and Thomas pursued a bachelor’s degree in biology. The outdoor world fascinated him.

He moved into a cabin with Chris J.D. Zarafonetis, a native Texan by way of Grand Rapids who also wanted to be a doctor. Both men had just completed their U-M master’s degrees; Weller also was in his first year of graduate work at Harvard. A Station veteran, he was starting his third summer in the woods and was captivated by parasites, particularly those found in yellow perch swimming in Douglas Lake.

Weller and Zarafonetis bunked in a tin shack nestled along Upper Drive West, recording their names in black paint on a wall. They would continue to be known for decades for their accomplishments.

Chris Zarafonetis would go on to a distinguished career with his alma mater and the U.S. Army, serving in three wars and rising to the rank of colonel with the Medical Corps. He held three Michigan degrees and, as a longtime U-M professor, specialized in understanding and combating blood diseases.

Weller joined the faculty of Harvard University, where he received his medical degree in 1940. He, too, would serve with the Army Medical Corps during World War II. His zeal for understanding parasites fueled what a biographer called Weller’s “lifelong obsession” with tropical medicine and virology. That passion, in turn, led to understanding how the polio virus could grow and thrive.

For his research breakthroughs, Weller was one of three scientists to receive the 1954 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Years later, he would credit Biological Station faculty members – Director George LaRue, Lyell J. Thomas of the University of Illinois, and William W. Cort of Johns Hopkins – with shaping his career.

Weller said his days at Douglas Lake were “my three most happy and productive summers.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Future Nobel Laureate Thomas Weller spent three summers at the Biological Station.Image: Daryl Marshke, Michigan Photography

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Cabin messages offer plenty of encouragement.Image: Daryl Marshke, Michigan PhotographyChapter 6 “This Place Was Tough”

When he was acting director in the early years of Bug Camp, Professor Henry A. Gleason worried that too many botanists and zoologists around the country were ignoring fieldwork.

“ … [S]cience has moved indoors, and we have produced a race of scientists who are as complete strangers to the field as their predecessors were to the laboratory. We have taught the anatomy of the frog to students who never saw him by his native ponds; we have shown the pollen tubes of flowers to students who never saw an insect engaged in the act of pollination; we have discussed adaptations with students who never saw the wonderful mechanism or the brilliant colors of an orchid in the bog.”

The Biological Station, he said, was changing how to study the mystery and wonders of nature: “The reign of the closet biologist is over.”

Fieldwork can be hard, dirty, frustrating, rewarding, and consuming. Bug Camp is, first and foremost, an academic research environment that today offers 10,000 acres for study. The type of total immersion encouraged by Gleason – and experienced by generations of Bug Camp students – comes through on cabin walls. In the solitude of private space, campers have recorded all manner of emotions stirred by their time in forests, lakes, streams and swamps.

“I won’t lie, this place was tough,” a student wrote in an undated message. “The weather sucked most of the time, the bed sucked all of the time and the workload was constantly high. But I made great friends and I proved I could handle it. I know the first few days are rough, but just wait till the square dance, then you’ll see. Good luck and godspeed.”

The “Slime Sisters” of 1997 – Christa Shulters and Tiffany Rine – were effusive: “We love algae!”

More on freshwater algae:

Oedogonium, Oedogonium

My life is a spirogyra

Maybe I’m a schizothrix

I could just Diatoma,

Stick me in a cryptomonas,

Under the Asterionella

Erin Eberhard, studying limnology and ecology in 2013, advised: “Learn lots and enjoy all that is around you with an awesome group of friends. Don’t forget to always have a flashlight.”

More than one student has left behind the words of Henry David Thoreau: “I went to the woods because I wanted to live deliberately.”

Erik Viik invoked a Native American proverb when he was a researcher in 1996: “Treat the earth kind; it was not given to you by your parents. It was loaned to you by your children.”

Cabinmates Nikki and Liz scribbled ten Bug Camp recommendations during their 2015 stay. Among them: “Don’t get pneumonia.” “Embrace the country music.” “Go hard or go home.” There also is a crass yet familiar anatomical suggestion about Ohio State.

From a 2011 camper: “Allow this place to be your haven. See yourself as you are, without the influence of ‘home.’ Without friends, family, reputation, mistakes, corruption, society, gadgets, and manmade excuses for plastic happiness.”

From 2013: “The summer I stopped being scared.”

From 2015: “This place will free your soul.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

There are no frills in a Biological Station cabin.Image: Daryl Marshke, Michigan PhotographyChapter 7 “A Very Distinctive Camp Sound”

An old Bug Camp story goes like this: A veteran camper travels to nearby Pellston to collect a new summer arrival from the bus station. Rolling into camp, the newcomer looks around and says, “What are all these tool sheds used for?”

The veteran responds: “This one’s yours.”

When Laura Rood arrived in the summer of 1983 as a U-M junior, the tin cabins struck her as rustic at best (“Depression-era and makeshift”).

“My brother saw them and said they looked like they could be opened with a can opener. A very distinctive camp sound was the break of a screened door opening against its complaining spring, followed by a bang as the door closed.”

Time is now closing in on the rustic residences. The sights and sounds of cabins that have charmed (or irritated) campers since 1914 are in transition, as today’s students want better amenities, even in the forest. New cabins – insulated and with private baths – are being considered to complement the old, some of which will remain. The modernization, including camp-wide utility upgrades, will allow the Biological Station to operate cabins year-round.

There are also discussions about preserving some of the old steel walls and their colorful graffiti to build into the new residences and display around the grounds. Doors to the modern cabins should begin opening in 2025.

The bugs will be waiting.

Sources:

U-M Biological Station website; Report of the Director of the Biological Station to the Board of Regents, 1909, Jacob Reighard; Camp Davis report, 1916; The University of Michigan Biological Station, 1909-1983, David M. Gates, editor; Grapevine to Pine Point: The University of Michigan Biological Station, Mary Crum Scholtens and Kevin Williams, editors; Botanical Observations in Northern Michigan, by Henry A. Gleason, Journal of The New York Botanical Garden, December 1923; The University of Michigan, An Encyclopedic Survey; Thomas Weller, 1915-2008, a biographical memoir, by Kenneth McIntosh; George A. Fuller company, general contractors, 1882-1937; a book illustrating recent works of this organization.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

A student scrapbook from 1916 celebrated the end of that summer's cabin construction.Image: U-M Engineering Communications & Marketing records, Bentley Historical Library

-