Professor White’s Diag

By James Tobin

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Without permission from anyone, I began planting trees.– Andrew Dickson White

-

Chapter 1 “Unkempt and Wretched”

The Ann Arbor campus was barely 20 years old when Andrew Dickson White first saw it. Just married, he arrived from Yale in October 1857 to teach history and English literature. He was only 24, the youngest member of the faculty, and he looked even younger. In fact, a student at the train station mistook him for an entering freshman and showed him all the way into town before realizing the newcomer was a professor.

It was the time of year when Michigan’s leaves are aflame in yellow and red, and White’s first impression as he entered the village, he wrote later, was of “a beautiful place.” But he saw one glaring drawback.

“The ‘campus’ on which stood the four buildings then devoted to instruction, greatly disappointed me,” he later wrote. “It was a flat, square inclosure of forty acres, unkempt and wretched. Throughout its whole space there were not more than a score of trees outside the building sites allotted to professors; unsightly plank walks connected the buildings, and in every direction were meandering paths, which in dry weather were dusty and in wet weather muddy. Coming, as I did, from the glorious elms of Yale, all this distressed me…”

A scrubby field was no fit place for learning, and he was not going to leave it that way.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Andrew Dickson White would make his mark as a historian with the publication of the two-volume History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896).Image: Available online at Rare Book and Manuscript Collections Cornell University.

The ‘campus’ on which stood the four buildings then devoted to instruction, greatly disappointed me.

– Andrew Dickson White -

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

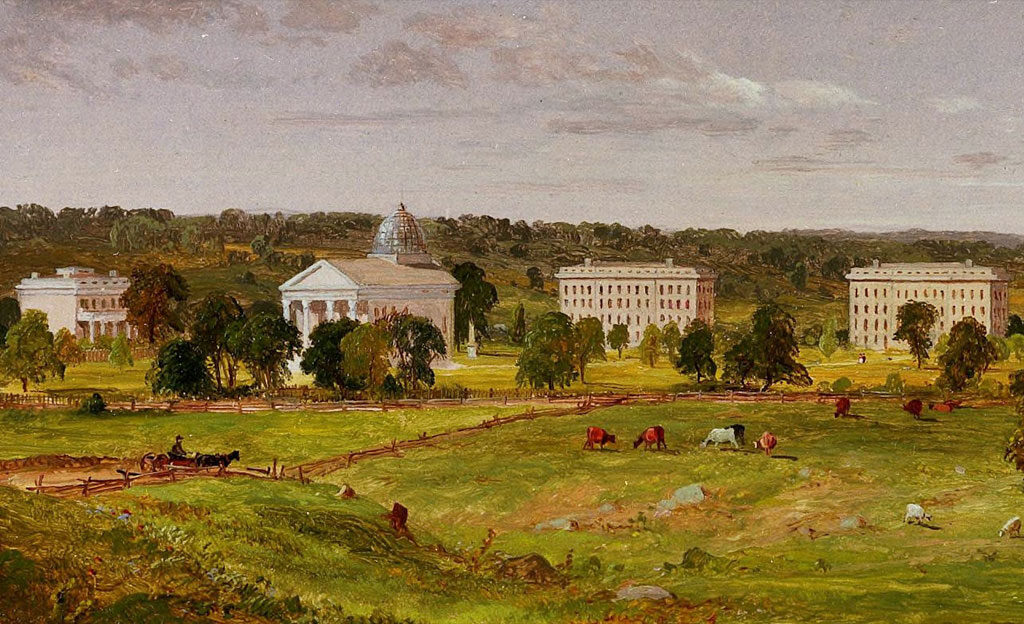

The artist Jasper Cropsey’s painting—one of the earliest images of the new campus in Ann Arbor—showed only a scattering of trees.Image: Available online at Bentley Image Bank and in the Jasper Cropsey Visual Materials, Bentley Historical Library.Chapter 2 A Personal Project

White asked around: Why so few trees?

Well, people said, it wasn’t that no one had tried.

In the early ’50s, Dr. Edmund Andrews, who doubled as professor of anatomy and superintendent of grounds, had rounded up some citizens and students for a program to plant a thousand trees. But most of the seedlings died. People said the ground was too hard and dry.

White didn’t believe it. In the village blocks west of the campus, he saw plenty of “fine large trees, and among them elms” growing in “the little inclosures about the pretty cottages.” And you only had to look at the virgin woods nearby to know the soil was perfectly well suited to trees.

White decided the problem must have been lack of proper care. So, with neither permission nor funding, he took matters into his own hands.

First, he observed the human geography—the paths that students had created simply by walking between buildings. No doubt he had in mind the same principle voiced some years later by President James Burrill Angell, who told students that “one of the finest examples of the value of precedent that I have ever seen is one of the paths which you fellows make across the grass of the Campus. We take that as clear proof that a walk should be there, and set about building one.”

The fashion in landscape design just then was to create outdoor corridors shrouded in green canopies. This was the effect White wanted. So he marked off several walkways—including, apparently, the basic X of the Diag—and set to work.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

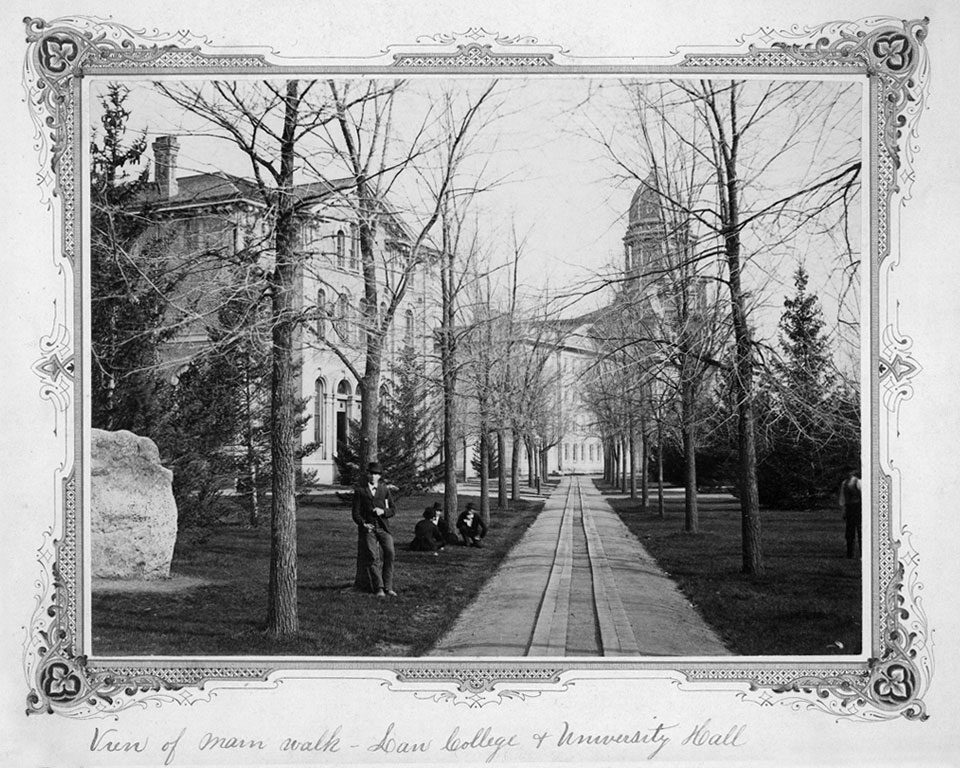

This early photograph of the original Mason Hall (at right) and South Hall—U-M’s first two classroom buildings—shows seedlings likely planted by Professor White.Image: Available online in Bentley Image Bank and in the Photographs Vertical File, Bentley Historical Library.Chapter 3 “The Light of History”

“Without permission from anyone,” he would write in his Autobiography, “I began planting trees within the University enclosure; established, on my own account, several avenues; and set out elms to overshadow them. Choosing my trees with care, carefully protecting and watering them…and gradually adding to them a considerable number of evergreens, I preached practically the doctrine of adorning the campus. Gradually some of my students joined me; one class after another aided in securing trees and in planting them, others became interested, until, finally, the University authorities made me ‘superintendent of the grounds,’ and appropriated to my work the munificent sum of seventy-five dollars a year.”

Not that White was neglecting the work he had been hired for.

His devotion to history had arisen as the Northern and Southern states approached a collision in their long dispute over slavery. White was an abolitionist, but he felt a particular calling apart from politics. “Though I felt deeply the importance of the questions then before the country,” he wrote, “it seemed to me the only way in which I could contribute anything to their solution was in aiding to train up a new race of young men who should understand our own time and its problems in the light of history.”

After graduating from Yale, he took more training in Berlin and Paris, then returned to New Haven for a master’s degree. In American colleges very few courses were devoted solely to history, and most classes consisted of droning recitations out of textbooks. But in Europe, White heard professors give sparkling talks that treated history as “a living subject having relations to present questions.” He thought he might do the same in America. “Great as was my love for historical studies, there was something I prized far more—and that was the opportunity to promote a better training in thought regarding our great national problems then rapidly approaching solution, the greatest of all being the question between the supporters and opponents of slavery.”

The question was where he would do this work—in the East, or somewhere new.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Young elms grow along Diag walkways laid out by Professor White. At right, in the background, is the rear of the President’s House.Image: Available online in Bentley Image Bank and in the Photographs Vertical File, Bentley Historical Library.Chapter 4 “Hardy, Vigorous, Shrewd…”

Friends who heard White’s ideas about teaching urged him to stay in the East and join the faculty at Yale. But on the day of his commencement as a master’s candidate, he heard an address by President Francis Wayland of Brown University, who told the graduates: “The best field of work for graduates now is in the West; our country is shortly to arrive at a switching-off place for good or evil. [He meant the coming clash between North and South.] Our Western states are to hold the balance of power in the Union, and to determine whether the country shall become a blessing or a curse in human history.”

“I had never seen him before,” White wrote. “I never saw him afterward. His speech lasted ten minutes, but it settled a great question for me. I went home [to upstate New York] and wrote to sundry friends that I was a candidate for the professorship of history in any Western college where there was a chance to get at students, and as a result received two calls—one to a Southern university, which I could not accept on account of my anti-slavery opinions; the other to the University of Michigan, which I accepted….”

It was a very good match. Michigan’s president, Henry Philip Tappan, spotted White as just the sort of bright young scholar who could help fulfill Tappan’s vision of a citadel of higher learning dedicated to the public good. White’s students liked him and he returned their respect. They were “worth teaching,” he said, “hardy, vigorous, shrewd, broad, with faith in the greatness of the country and enthusiasm regarding the nation’s future. It may be granted that there was, in many of them, a lack of elegance, but there was neither languor nor cynicism. One seemed, among them, to breathe a purer, stronger air….

“I soon became intensely interested in my work, and looked forward to it every day with pleasure.”

And when classes were over for the day, Professor White went outside to check on his trees.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

This tree-lined walkway points southeast toward University Hall, which stood about where Angell Hall stands now. At left is the Law Building, later named Haven Hall.Image: Available online in Bentley Image Bank and in the Photographs Vertical File, Bentley Historical Library.Chapter 5 “Splendid Growth”

For two years he nursed his seedlings. He pruned them and protected them from insects. In the heat of summer he made sure they had enough water. They survived, then thrived and grew.

Students began to join him. Young men soon to board trains for Southern battlefields went out to the woods around Ann Arbor and returned with seedlings. Two nurserymen from New York sent a gift of 60 trees that were planted in a grove near the northern edge of the central grounds. The class of 1858 placed 50 young maples in concentric circles around the great native oak. White added more maples along one side of the fence that bordered State Street on the west. The literary faculty donated 42 elms for the other side of the street.

“So began the splendid growth that now surrounds those buildings.”

For two years he nursed his seedlings. He pruned them and protected them from insects. They survived, then thrived and grew.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

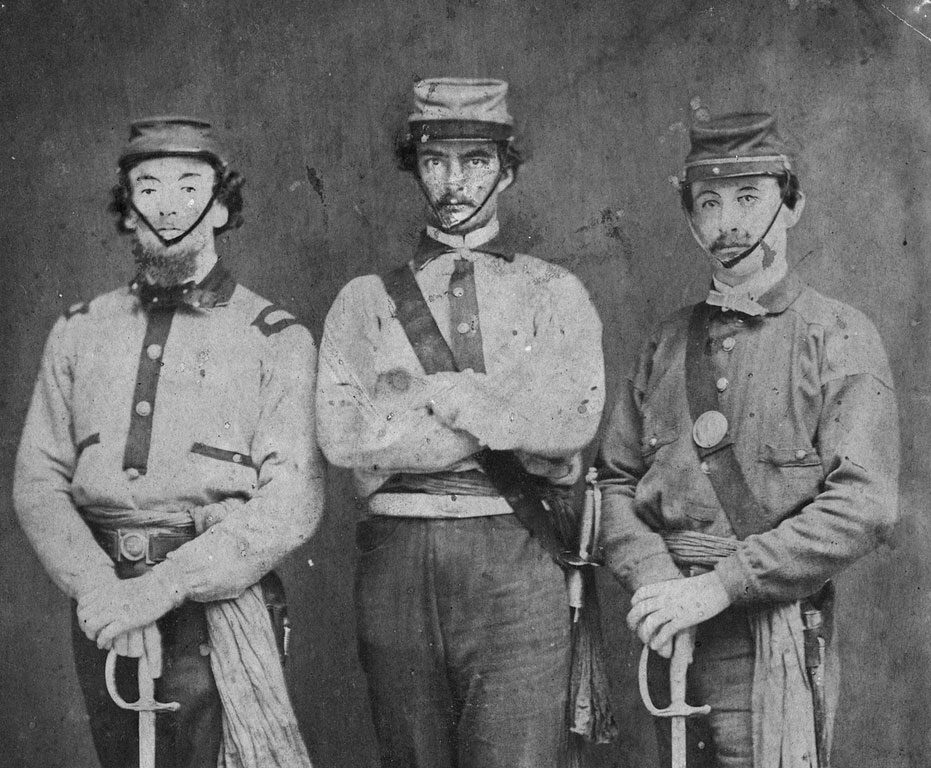

The captains of U-M’s three student companies in 1861, as the Civil War began—classmates of the students who helped Professor White plant his trees.Image: Available online in Bentley Image Bank and in the Photographs Vertical File, Bentley Historical Library.Chapter 6 “As My Own Children”

White tended the trees, taught his students, and began the research and writing that would make him one of the leading American historians of his generation. Then, in the spring of 1861, the Civil War began, “and there came a great exodus of students into the armies,” he wrote, “the vast majority taking up arms for the Union, and a few for the Confederate States. The very noblest of them thus went forth—many of them, alas, never to return, and among them not a few whom I loved as brothers and even as my own children.”

As the war approached its climax, White’s father died, and he had to go home to manage his family’s business affairs. Almost immediately he was elected to the New York state legislature. In 1865 he co-founded Cornell University and became its first president.

For a number of years he retained a lectureship at Michigan and returned periodically to teach, but after a while his duties in Ithaca made that impossible, “and so ended a connection which was to me one of the most fruitful in useful experiences and pregnant thoughts that I have ever known.”

But those trees in Ann Arbor remained “to me as my own children.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Andrew Dickson White in 1902, as president emeritus of Cornell and former U.S. ambassador to Germany and Russia.Image: Available online at Rare Book and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University.Chapter 7 “More Trees Than Boys”

White was president of Cornell until 1885; U.S. ambassador to Germany from 1879 to 1881; minister to Russia from 1892 to 1894; president of the American Historical Association; and president of the American Social Science Association. As the 20th century began he continued to write and speak widely.

Down through the decades of his long life, he returned to Ann Arbor from time to time to see friends and give lectures. He always visited his trees “to see how they prosper, and especially how certain peculiar examples are flourishing.” On one visit, he was seen out on the Diag at night, going from tree to tree with a lantern.

At Cornell in the spring of 1911, he had a sudden whim. From his papers he pulled out an old map, then boarded the train for Ann Arbor.

The next day, on the Diag, a student recognized the old man walking slowly from tree to tree, looking from his map to the trees. The student asked him what he was doing.

“Yesterday,” he said, “while sitting in my library at Ithaca, I happened to think that fifty years ago today the class of 1861 planted these trees under my direction. I had among my papers a plot of the ground, the location of each tree and the name of the student who planted it.”

He gestured at the trees and said: “There are more trees alive than boys.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Elms planted by Andrew Dickson White in the 1850s and ’60s still dominated the Diag when this photo was taken in the 1930s.Image: Available online in Bentley Image Bank and in the Photographs Vertical File, Bentley Historical Library.Chapter 8 14,000 Trees

The tall native oak that White saw on his first visit to the campus still stands just west of the Hatcher Graduate Library. Since 1858 it has been called the Tappan Oak, to honor the president who launched the modern University of Michigan and, among other foundational acts, hired Andrew Dickson White.

Nearly all of White’s elms went down in the plague of Dutch elm disease that crept across Michigan in the 1960s and ‘70s.

Nearly all, but not quite.

On the last morning of May 2011—150 years after the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter— U-M foresters took a last look at a massive elm in the northwest corner of the Diag. Dutch elm had weakened it. The foresters had tried to keep it alive. Now it was beyond saving. It was a hazard. By nightfall they had brought it down.

They counted the rings—not an exact science with a large, multi-lobed elm—and concluded the tree was at least a century and a half old. It was almost certainly one of White’s. They think a few others still survive.

A few weeks later, a few yards away, they planted a sugar maple to take the old-timer’s place.

For a time, that maple was the youngest of some 14,000 trees that stand on the Ann Arbor campus. But that distinction is now claimed by an even younger tree, a bur oak given by students, faculty and staff to commemorate the inauguration of Mark Schlissel as Michigan’s fourteenth president. If all goes according to plan, it will grow tall in the northwest corner of the Diag, about where Andrew Dickson White stood when he first saw the campus.

-

Chapter 9 On the Diag

The beauty of the Diag is improvisational. It is less elegant than a formal landscape design, but more comfortable, even homey, partly because the trees have been planted piecemeal. They were planted here and there as buildings came and went and as walkways changed, creating a particular sense of place that has changed over time, but only gradually, so that each generation has had its own Diag, slightly different from the Diag of the generation before and after.

In 1940, when the U.S. was preparing for its all but inevitable entry into World War II, an anonymous writer captured the feelings of a moment at the center of the campus:

“A warm summer day has given way to a perfect summer night, overcast but with a quarter-moon breaking through the clouds above the campus trees. It is a few minutes past nine as you swing onto the Diagonal. The darkness insulates you, the air is caressing; you move almost effortlessly under the long aisle of trees. It is quiet except for the insistent cheeping of insects among the leaves, and occasional distant voices….

“This is the heart of a great university; warm, tranquil, peaceful, democratic. It is one of the things worth preserving.”

This story is an expanded version of an earlier article (“Professor White’s Trees,” Michigan Today, March 2008) combined with a video script that was the basis for “A Tree Grows on the Diag,” Michigan Today, July 2011. Sources include The Autobiography of Andrew Dickson White, vol. 1 (1905); Anne Duderstadt, The University of Michigan: A Photographic Saga (2006); “The Trees on Michigan’s Campus,” Michigan Alumnus, January 1923;”Campus Paths – Old and New,” Michigan Alumnus, December 1922; Dr. W.F. Breakey, letter to the Michigan Alumnus, April 1901; and Elizabeth M. Farrand, History of the University of Michigan (1885).

The darkness insulates you, the air is caressing; you move almost effortlessly under the long aisle of trees.

– Anonymous