“The Dignity of Man”

By Kim Clarke

enlarge

enlarge

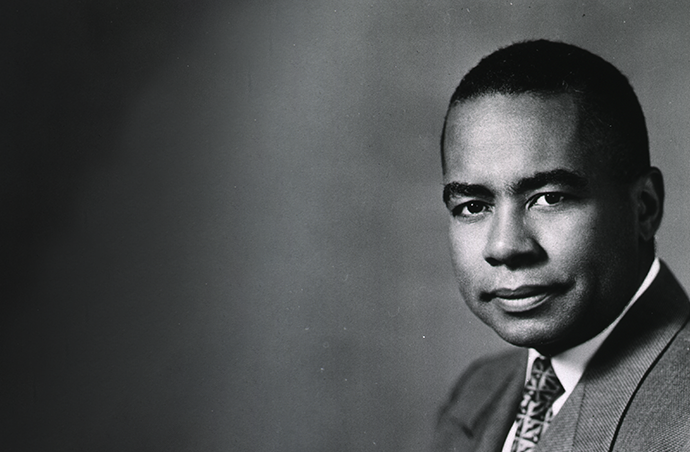

Caption

All of us will have to change our way of thinking much more drastically than we have had in the past.– Paul B. Cornely

-

Chapter 1 Death and Dying

Juliette Derricotte was 34 years old when she died of traumatic head injuries suffered in a horrible car crash.

She had been a passenger riding along the roads of rural Georgia with students from Fisk University, where she was the dean of women. Forced off the road by an oncoming car, Derricotte and her young charges were thrown from their vehicle, bones snapping and fracturing as they slammed into a ditch. Their driverless car rolled on top of them.

Derricotte was rushed to the closest hospital. Doctors took one look and refused to admit her: Juliette Derricotte was Black, and Dalton’s Hamilton Memorial Hospital treated only white patients. After lingering for hours, Derricotte was lifted into an ambulance and hurried to a segregated hospital some 30 miles away in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Her brain swollen and skull fractured, Derricotte died before the driver could complete the journey.

It was late 1931.

Some 450 miles away, Dr. Paul Cornely was a first-year medical intern working in a segregated hospital in Durham, North Carolina. He had graduated with honors from the University of Michigan Medical School just months earlier.

The unnecessary death of an African American woman, hastened by the discrimination of white doctors because of her skin color, and segregated hospitals like the one where he worked, became the driving forces of Cornely’s life work. Racism, he said, was a virus that was killing Black people and sickening society. For the next 40 years, he would be a fierce champion of equal health care for all, leading to the desegregation of America’s hospitals.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Cornely, in the center of the middle row, joined the Negro-Caucasian Club in 1927.Image: Michiganensian 1928Chapter 2 “Racism was Rampant”

Paul Cornely moved around a lot before being drawn to Ann Arbor.

He was born in the French West Indies to a Chilean mother and West Indian father. The Cornelys moved to Puerto Rico in 1909, when Paul was 3, and stayed for a dozen years. Next came a year in New York City before settling in Detroit when Paul was 16. His dad, Eleodore, went to work in a foundry and his mother, Adrienne, stayed home raising Paul and his younger siblings, Antoine and Lily.

After graduating from Detroit’s Central High School, Cornely took two years of classes at the College of the City of Detroit, a precursor to today’s Wayne State University. He enrolled at U-M in 1926, attracted by its low costs and location close to home. His father had talked him out of studying engineering and pushed him toward medicine, saying a career as a doctor would be more lucrative and sustaining for a Black man.

Cornely joined Omega Psi Phi, the African American fraternity that had a house on Catherine Street. And he became one of the earliest members of the Negro-Caucasian Club, created in 1926 by African American and white students with the ambitious commitment to the “abolition of discrimination against Negroes.”

Of some 13,000 students at U-M, fewer than 100 were African Americans. Campus swimming pools, dances, residence halls – all were off-limits to Black students. “Racism was rampant in many areas of the city and the University,” Cornely said years later.

With several club members, Cornely sat down at Ann Arbor lunch counters whose owners refused to serve African American diners, claiming their presence would drive out paying white patrons.

Nothing happened.

“We ‘sat in,’ not to wait for service, but to count the number of whites who walked out because they saw Negroes sitting there,” recalled club member Lenoir B. (Smith) Stewart. “The total count was NONE. …This convinced the business people that they had not a leg on which to stand.”

Stewart, Cornely and other club members invited prominent African Americans to campus to speak, knowing administrators would never do so. The writer Alain Locke, the first African American Rhodes scholar, said young Black people were preparing to challenge racism and fight for equal rights by showcasing their abilities. Robert W. Bagnall, an executive with the NAACP, appeared at Lane Hall. The poet Jean Toomer drew a crowd to the Natural Science Auditorium.

Civil rights leader W.E.B. DuBois called for white Americans to accept Black people as equals, saying there was no redeeming quality to racial segregation.

“There is no place where he can go and still have a feeling of friendliness toward the white man, for wherever there is segregation, there is a constant hatred brewing on each side,” DuBois told a crowd in the Natural Science Auditorium. “There is no remedy by segregation which is possible, and the countries of the world have their eyes on the manner in which the United States solves the problem, so it is indeed an important one to be considered in our life of today.”

This was the intellectual swirl surrounding Paul Cornely as he worked his way through pre-med studies.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Cornely was one of four African American men in his U-M Medical School graduating class in 1931.Chapter 3 Paying the Bills

After graduating in 1928, Cornely enrolled in medical school intent on becoming a thoracic surgeon; he was one of four Black men in a medical class of 160 students.

And then the global economy crashed, and the Depression pulled down the Cornely family.

Cornely’s father lost his job and the family lost their home, forcing them to move into an apartment building where Eleodore Cornely went to work as a janitor in exchange for free housing. Adrienne Cornely began cleaning other people’s homes. And Paul Cornely wondered if his dream of becoming a doctor was ruined.

Grades were not a problem. He was outstanding in the classroom and became the first Black student at Michigan inducted into the Alpha Omega Alpha medical honorary society. But the part-time jobs he had worked – waiting tables during the academic year and working in a Detroit factory during the summer – no longer existed.

“There was always the question as to whether or not I would come back the following year,” he said.

He was rescued financially by the Julius Rosenwald Foundation, which awarded fellowships to African American college students. With one of seven Rosenwald fellowships awarded nationally to Black medical students, Cornely could pay his tuition and bills and graduated in 1931. He wanted to remain in Ann Arbor and intern at University Hospital, but young Black doctors, even those who weeks earlier had earned a U-M medical degree, were not allowed to join the house staff.

(Said Dr. Watson Young, an African American who graduated from Michigan’s Medical School in 1942 and encountered the same discrimination: “At the medical school, when you put on that white coat and when you get in the classroom, you’re all equal. But as soon as you leave the classroom, as soon as you graduated from the University as a student, the hospital was no longer available to you as an intern, as a resident.”)

Cornely instead moved on to Durham and its segregated Lincoln Hospital. It was here where he began to see firsthand how racial segregation damaged the health of African Americans. And it was in Durham where his education pushed him back to Ann Arbor and into a new direction that he worried was “second class.”

There was always the question as to whether or not I would come back the following year.

– Paul Cornely -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Cornely was intrigued by the prospect of graduate studies in public health with Professors John Sundwall, left, and Nathan Sinai.Image: University of Minnesota (Sundwall); Detroit Free Press (Sinai)Chapter 4 “Missionary Zeal”

While Cornely was treating patients at Lincoln Hospital, the dean of Howard University’s College of Medicine made him an offer: Return to school and earn your doctorate in public health, and we’ll hire you to teach at Howard.

Dr. Numa P. G. Adams was scouring the country for bright young African American doctors like Cornely to join the faculty at Howard, a historically Black university in Washington, D.C. Adams offered Cornely a two-year fellowship that would cover his cost of graduate school.

Cornely hesitated. His time in medical school had taught him that public health “was considered to be a second-class subject.” It meant confronting the vast ills of society rather than the more precise work of treating individual patients.

But he also thought about his very first year at Michigan, when he had a class with John Sundwall, director of the University’s Division of Hygiene and Public Health. Sundwall was big, gruff, and stingy with a smile. But he believed in public health, and that passion swayed Cornely. “The characteristics which most impressed me about him,” Cornely said, “was his missionary zeal to spread public health throughout every nook and corner of the U.S.”

He had noted a particular lesson Sundwall imparted: The medical world was ignoring the social and environmental factors that killed people.

Cornely had been equally in awe of Nathan Sinai, a professor of public health who taught an introductory health course. Sinai was the antithesis of Sundwall: He exuded elegance with a graceful approach to everything he did, including his impeccable wardrobe. His lecture style made it possible for 300 students to feel like he was speaking to each one individually. It was a course that Cornely never forgot.

“This was the subliminal experience which caused me to select public health for graduate study,” Cornely said, “and return to Michigan to have him as my preceptor five years later.”

Sinai guided Cornely’s dissertation on post-graduate medical education and the training needs of physicians. Sundwall exposed him to the inner workings of the campus health service and how it cared for students. Cornely had became a public health convert.

When he graduated in 1934, Cornely was the first Black man in the country with a doctorate in public health.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Dr. Numa P.G. Adams was the first African American dean of Howard University's College of Medicine.Image: Library of Congress

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Cornely lecturing at Howard University, where he was a professor of preventive medicine and public health.Image: Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University Archives, Howard UniversityChapter 5 “This Ever-Growing Challenge”

Paul Cornely moved to the nation’s capital and spent the next 39 years at Howard University. He taught students, became a department chair, directed the student health service, and became the medical director of Freedmen’s Hospital, Howard’s teaching hospital that served the local African American community.

His research through the decades demonstrated over and over how poorly the medical community was treating black people. Mortality rates for African Americans far outpaced white people, particularly in the rural South, where most Black people lived before World War II. The leading causes of death: tuberculosis, heart disease, pneumonia, venereal disease, and childbirth complications that killed mothers and babies. All were preventable.

The dying was not limited to the South. Cornely’s brother Antoine died in 1936 in a Black hospital in Detroit when infection set in after stomach surgery. He was 14.

Looking at data from 1920 to 1940, Cornely found that life expectancy was dropping for African American men and women and increasing for white people. Again, tuberculosis, heart disease, and complications from childbirth were to blame. “The Negro is being yearly outdistanced and the gap gradually widening,” he wrote.

Cornely saw many causes, all rooted in racism: a shortage of Black physicians because white medical schools refused to enroll African Americans; under-funded segregated hospitals forced to work with outdated equipment and not enough beds; discrimination against African Americans at white-run hospitals and clinics; a lack of health insurance; drug companies that exploited patients and physicians; and medical societies that shut out Black physicians and dentists.

“What are the motley group of voluntary and official health organizations and the army of health workers planning and formulating to meet this ever-growing challenge?” he wrote in 1941. “Let us all objectively meet this problem so that the future twenty years will see greater progress.”

It would take much longer.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The campus of Howard University in 1942.Image: Library of Congress

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Cornely was a prolific writer, contributing to academic journals, newspapers and magazines.Image: Negro Digest, June 1946Chapter 6 Jim Crow Hospitals

In 1954 the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its landmark ruling, Brown v. Board of Education, that desegregated public education nationwide and made “separate but equal” schools illegal.

Another nine years would pass before segregated health care was outlawed.

“Equality in health care remained an elusive dream for black persons until the stage was set for massive federal intervention,” writes Dr. P. Preston Reynolds, a University of Virginia professor who studies the history of racial integration in American medicine.

Following World War II, new legislation known as the Hill-Burton Act provided federal dollars for the construction and expansion of hospitals, particularly in rural areas desperate for medical care. It also allowed hospitals to use that money for all-Black hospitals under the guise of separate-but-equal care. That led to some 2,000 taxpayer-supported medical facilities in the South that either shut out or segregated African American patients and physicians.

Despite the best intentions of Black physicians, segregated hospitals could not compete with hospitals for white people and “are only high-grade convalescent homes,” Cornely wrote.

Working with two other Black physicians –W. Montague Cobb and Louis T. Wright – Cornely joined with the NAACP to target Hill-Burton and its Jim Crow funding model. “Segregation and discrimination are environmental factors and are just as damaging to health as water pollution, unpasteurized milk, or smog,” Cornely said on more than one occasion.

The physicians relied upon political activism and scientific research that showed how poorly African Americans fared under “separate-but-equal” care. “[They] saw the integration of hospitals as the best way to improve the health of black persons because they knew that a separate hospital system would never match the quality of health care facilities that were available for black persons,” Reynolds writes.

The legal case for ending Jim Crow hospitals came in 1962, A group of Black doctors and dentists in Greensboro, North Carolina, sued to integrate private, all-white hospitals in their city that had received Hill-Burton dollars. In a landmark ruling a year later, a federal appeals court said segregation in hospitals built with federal dollars was unconstitutional.

Any hospital that had used or planned to accept Hill-Burton aid was now required to open its doors to Black patients and physicians.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Cornely and U-M Medical School classmates at a 1956 reunion in Ann Arbor.

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Cornely served as medical director for the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.Image: National Library of MedicineChapter 7 “Insensitivity and Apathy”

Cornely did not rest, because medical care for Black citizens continued to be second-class despite court rulings and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

He excoriated Washington’s dental society for having members who refused to treat Black patients, with one dentist bragging, “I don’t work on them.”

“When is the responsible white leadership in this nation’s capital going to rise up with righteous indignation against these practices and enunciations?” Cornely asked in 1964. “The white leadership cannot afford to sit supinely by in smug indifference. Whether they believe it or not, they have as much at stake, and possibly more, than the Negro leadership.”

He wrote a regular column that was syndicated in African American newspapers nationwide.

He toured impoverished neighborhoods in big cities and rural towns, calling out “health brutality” and telling Congress in 1969 that 30 million Americans, white and Black, were living “in conditions we would not let our animals endure.”

He was known for working behind the scenes, but he was not afraid to sit before members of Congress to tell them Black and poor people were being left behind. Poor people desperately needed clean, safe housing, better health insurance from the government, and a human services system that genuinely cared. “I think insensitivity and apathy which we found on the part of agencies for human services in many cities and areas throughout the United States have brutalized people,” he told a Senate committee in 1969.

That same year, Cornely was elected president of the American Public Health Association, the professional organization representing the discipline he had been so hesitant to pursue as a career in the early 1930s. Not only was he the first Black man to lead the APHA, he was the first African American to lead any large professional medical organization in the country.

The white leadership cannot afford to sit supinely by in smug indifference.

– Paul Cornely -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Cornely was the first Black man to lead the American Public Health Association.Image: Pittsburgh Post-GazetteChapter 8 “Redefine the Unacceptable”

Thirty-five years after receiving his medical degree from Michigan in 1931, Paul Cornely approached an audience of predominantly white faces gathered in U-M’s School of Public Health building.

He was a 60-year-old Black man who had fought for adequate health care for poor people, particularly African Americans. He had marched on Washington with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and testified before congressional committees about the shabby condition of segregated hospitals in the South. He never stopped advocating for racial integration and equity.

And still, standing before public health faculty and students in 1966, he knew people viewed him differently because of his skin color.

“The behavior and attitude of every person in this room, and every man and woman who has studied here, has been warped by what he has heard about the Negro or by the practices of segregation and discrimination which he has helped institute, foster, or tacitly accept,” Cornely said.

“In the many years which I have attended professional meetings, it has been interesting to watch the performance of many of my colleagues – from those who overcompensate and believe that everything I do is wonderful, to those who become busily engaged whenever I come nearby. There are all varieties between these two extremes, and there are very few who are truly emancipated.”

Yes, he said, health education was important; not enough Americans understood proper nutrition, the warning signs of cancer, or how to prevent sexually transmitted diseases. The country’s health care system was fragmented and ineffective. And America’s young people were becoming more and more overweight, portending health woes for their lives as adults.

But racism, he said, was the ultimate public health challenge. He called on schools of public health to better prepare their graduates for addressing the health challenges facing African Americans. That included a “decolorization” of attitudes and actions “so that the student would be released in part or whole of the bonds which bind him.”

“If we accept the premise that segregation and discrimination are as inimical to community health as air and water pollution and that racial prejudice is a form of mental illness,” Cornely said, “then they deserve as much consideration in the curriculum as these other subject matters.”

As he spoke to the audience, Cornely referred to notes he had taken nearly 40 years earlier as a student during a class lecture by John Sundwall. He told how Sundwall always pushed students “to move beyond the existing rigid walls of tradition or practice in order to give fuller meaning to the dignity of man.”

The lessons of Michigan continued to resonate decades after Cornely first walked onto the Ann Arbor campus.

“I believe that John Sundwall would want us to redefine the unacceptable in terms of racial prejudice, health ignorance, the deterioration of youth, and the inefficiency in the delivery of health and medical care,” he said. “To do this and do it successfully, all of us will have to change our way of thinking much more drastically than we have had in the past.”

-

Chapter 9 “An Overdue Honor”

Paul Cornely made several return visits to his alma mater, most often for reunions of his medical class. The Board of Regents awarded him an honorary degree in 1968. “Belying personal modesty,” regents said, “he is forthright in affirming the right of the disinherited to an optimal physical well-being.” At the time, only a handful of African American men had been so honored by U-M, including Ralph Bunche, Thurgood Marshall and Ralph Ellison.

Cornely’s proudest moment as an alum was the establishment of the Paul B. Cornely Fellowship, a School of Public Health postdoctoral award created in 1988 to increase underrepresented scholars in academic public health.

Cornely died in 2002, a month shy of his 96th birthday.

The School of Public Health now honors one of the University’s most influential public health advocates with the Paul B. Cornely Community Room – a designation that came after 25 student organizations called for it. Their successful petition in 2020 echoed sentiments voiced by Cornely through the decades.

“We believe that such an overdue honor,” students said, “will remind the community of the rich historical contributions by Black people to the School of Public Health, University of Michigan, and broader field of public health so often overlooked and forgotten.”

Sources: Paul B. Cornely Papers, National Library of Medicine; “The Negro-Caucasian Club: A History,” by Oakley C. Johnson, Michigan Quarterly Review, April 1969; Oakley C. Johnson Papers, U-M Special Collections Research Center; Paul B. Cornely alumni file, Bentley Historical Library; Dr. Watson Young oral history, Kellogg African American Health Care Project records, Bentley Historical Library; “Hospitals and Civil Rights, 1945-1963: The Case of Simkins v Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital,” by P. Preston Reynolds, Annals of Internal Medicine, June 1, 1997; “Public Health Imperatives for the Great Society,” by Paul B. Cornely, Thirteenth John Sundwall Memorial Lecture, April 4, 1966; African-American Medical Pioneers, by Charles H. Epps Jr., Davis G. Johnson and Audrey L. Vaughan; Notable Black American Scientists, edited by Kristine Krapp.

This article also draws on a sampling of the 100-plus scientific papers and journal articles written by Cornely, including “The Health Status of the Negro in the United States,” by Paul B. Cornely and Virginia M. Alexander, The Journal of Negro Education, July 1939; “Observations on the Health Progress of Negroes in the United States During the Past Two Decades,” by Paul B. Cornely, Southern Medical Journal, December 1941; “Race Relations in Community Health Organizations,” by Paul B. Cornely, American Journal of Public Health, September 1946; “Segregation and Discrimination in Medical Care in the United States,” by Paul B. Cornely, American Journal of Public Health, September 1956.