River Rat

By Kim Clarke

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Each moment might easily have been our last, but fortunately we were too busy to meditate upon our imminent untimely end.– Professor Elzada Clover, 1938

-

Chapter 1 “Anticipating the Thrill”

Floating down the Colorado River in a small wooden boat, Elzada Clover braced for the unknown.

In a few minutes she would enter the mouth of Cataract Canyon and 40 miles of angry, heaving rapids notorious for destroying oars, boats and men.

Behind Clover was a lifetime of teaching and exploring. She had overcome rheumatic fever as a child and influenza as a young woman. She had taught in a two-room school in rural Nebraska. Now, at 42 and solidifying her career as a University of Michigan scientist, she was staring at her most formidable challenge: a twisting ribbon of water known as the graveyard of the Colorado.

“I know we will be cut off from any hope of getting out in case of accident, illness or fright,” she scribbled in her diary, using a pencil to fill the lined pages. “Am really anticipating the thrill but know I’ll be petrified.”

Any fears were trumped by the prospect of unprecedented accomplishment and national attention. If her plan worked, she would not only discover new specimens to elevate U-M’s botanical gardens and broaden collections at the Smithsonian Institution. She would also make history as the first known woman to navigate the Colorado River.

What she couldn’t know was that she was about to learn even more about herself than the natural world.

-

Chapter 2 “Everything Will Be of Interest”

The Colorado River was no place for a woman.

Clover had heard this repeatedly as she planned the 1938 trip. It was the same opposition she encountered in academe and a world of science dominated by men.

The Botany Department was in the midst of accelerating its research, with faculty and students working in far-flung locations and gathering specimens for the university’s botanical gardens. As Clover planned her river venture, fellow scientists were in the Philippines, Colorado, and the Mexican states of Yucatan and Sonora. “What a lot of young researchers we have scattered all over, doing botanical work!” department chairman Harley H. Bartlett wrote in his diary. Bartlett himself had spent two decades visiting the world’s tropical regions to study plant genetics and mutations.

But the Colorado River expedition was different, and dangerous. The river was notoriously treacherous. When Clover first proposed the trip to discover new plants, Bartlett felt it was “a wild plan” and urged caution. “Of course I can’t say she can’t, but I told her it would be silly to do such a foolhardy thing without proper preparation for genuine work,” he wrote.

No woman had launched down the Colorado and survived. The river had claimed many men, too, with its force and fury. Knifing through seven American states and parts of Mexico over 6 million years, the river had created a deep, winding gouge in the earth best known for the Grand Canyon.

When Civil War veteran John Wesley Powell led the first successful scientific expedition down the river in 1869, the region was one of the last unexplored areas of the United States. “We seem to be in the depths of the earth,” Powell wrote from the floor of the canyon, “and yet can look down into waters that reflect a bottomless abyss.”

Nearly 70 years later, the river and the canyons it had carved were still a mystery to scientists. Clover was determined to change that by seeing firsthand what types of plant life existed in such a remote place. “This part of the West is inaccessible because of a complete lack of roads and trails. It has never been explored botanically and for that reason everything collected will be of interest,” she wrote in a successful proposal to the Rackham Graduate School to fund her research.

Months later, as Clover and two graduate assistants drove away from the Natural Sciences Building for their westward trek, Bartlett remained uneasy. Students Lois Jotter, 24, and Eugene Atkinson, 25, were just starting their careers in science, with Clover as their mentor.

“I wish they had never thought of anything so risky, but since all three are free, white and 21, and are going anyway, I can only be optimistic, help them all I can to make it a success, and hope for a lucky outcome.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Graduate students Eugene Atkinson and Lois Jotter flank Professor Elzada Clover.

-

-

Chapter 3 “Foolish, Reckless and Heedless”

The lone woman to attempt the river had been Bessie Hyde, who with her husband, Glen, set off in 1928 for their honeymoon. Both the trip and marriage were short-lived; the Hydes never reached their destination and their bodies were never found.

Now came a U-M professor and a graduate assistant named Lois Jotter. “Just because the only other woman who ever attempted the trip was drowned is no reason women have any more to fear than men,” Jotter told a reporter.

A year before Clover and Jotter attempted the river, the nation’s newspapers were filled with the heroics and heartbreak of Amelia Earhart’s effort to become the first woman to circumnavigate the globe. Now, with Clover’s river expedition, breathless accounts in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times and other papers never failed to cite the danger or the gender of its members.

Where the men were “adventurous,” the women were “flora-minded.” A male crew member was “bronzed,” while Clover was “bespectacled.” Jotter and Clover were “schoolma’ams,” and every wire story noted the women’s ages, while the men’s went unmentioned.

“One of our pet peeves was when people would ask us, ‘Do you think you could do everything as well as men can?’ And, of course, the answer always was, in terms of strength, that we probably could not,” Jotter recollected. “But certainly in terms of endurance we thought we could hold up pretty well.”

For Clover, the only kind of history she hoped to make would be discovering a new species along the riverbanks or canyon walls. She had initially planned to hike into the canyons and down to the riverbed, but a chance encounter with river runner Norman Nevills convinced her the water was the best route.

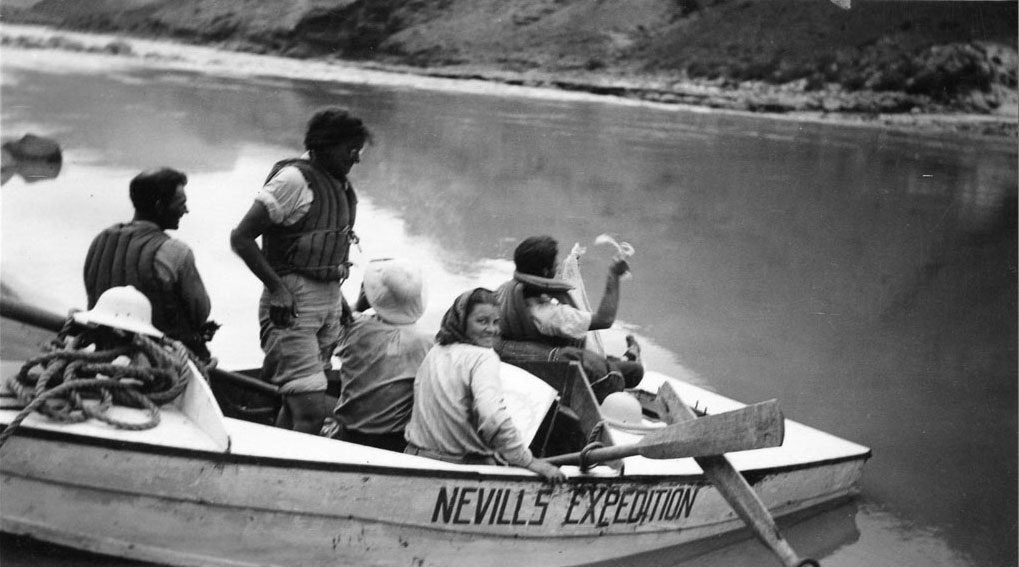

Based in Utah, Nevills lived along the San Juan River and was certain money could be made in river tourism. A successful, high-profile trip – say, with women scientists – could cement his career as a guide on the Colorado, San Juan and other rivers of the West.

Partnering with Clover, Nevills and the expedition would set out from the Green River in eastern Utah to Boulder City, Nev., to cover 666 miles through some of America’s most beautiful, isolated and dangerous landscapes.

When the expedition launched, an editorial writer at the Salt Lake Telegram condemned the adventurers for their presumed folly. The river was too high and too fast.

“For fame, for glory, for thrill or for swell obituaries, they are going down the river. If there is a special providence that watches over the blind and the drunken, let all hope that it will extend its protective care over the foolish, reckless and heedless.”

“Just because the only other woman who ever attempted the trip was drowned is no reason women have any more to fear than men.”

– Lois Jotter -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Elzada Clover sits on the rocks at the Hermit Rapids; Lois Jotter stands alongside the Mexican Hat.Chapter 4 “The Raging Devil Roar”

Rushing down the river in three green-and-white wooden boats, Clover and her crew members were a collection of strangers.

At 42, she was the oldest. In addition to teaching botany at U-M – where she had earned her doctorate – she was an assistant curator at the Botanical Gardens. Packing for the trip from her room at the Michigan Union, she carried several plant presses to preserve specimens. She also tucked away her harmonica and a bottle of Four Roses bourbon, a farewell gift from her colleagues.

The teaching assistants accompanying her came to the expedition with various interests. Jotter, the daughter of a U-M forestry professor, was studying both botany and biology. Atkinson was more intrigued by zoology, and intended to hunt during the trip. He was about to become the director of a new museum in western Michigan, and wanted specimens for wildlife displays.

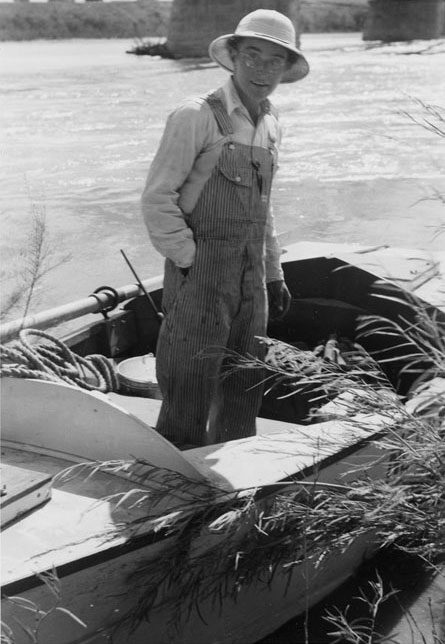

Nevills was 30 and had handcrafted the boats carrying him and the others. He named his pilot boat, the Wen, for his father: W.E. Nevills. Despite his experience building boats and running whitewater, Nevills had never traveled the full length of the Colorado.

Rounding out the crew was Don Harris, a 26-year-old engineer with the U.S. Geological Survey who helped construct the boats, and Bill Gibson, 24, a photographer and graphic artist from San Francisco.

All six knew the dangers. Once down the river, they would be alone. In some places, canyon walls that climbed 900 feet hemmed in the river and provided no possible exit. Baked by the sun, the gorges could radiate at 140 degrees. Sickness, infection, bruises, sunburn, broken bones – all were a threat when navigating submerged boulders, turbulent waters and slippery rocks. When the river did provide a sandy bank or rocky slope, rattlesnakes awaited the crew. All this was on Elzada Clover’s mind as the boats coursed down the river.

At first, crew members sang as they rowed, and Jotter heard a couple of the men make dark jokes about becoming the river’s next victims.

Then the boats approached Cataract Canyon. They heard the rapids, then saw the churning, boiling waters.

No singing now, Jotter noticed.

Two to a boat, expedition members rowed, floated and held tight. At some point, everyone blistered their hands rowing, was pitched into the river, or vomited after swallowing muddy water.

When the rapids were too daunting, they would either portage or line the boats. This was a backbreaking job that involved unloading and then roping the 600-pound boats, gripping and guiding them through the churning water while scrambling over boulders and other rocky debris. Other times, Nevills alone would shoot through the rapids, walk back upstream and repeat the process with the remaining boats; other members of the group would walk the length of the rapids.

“I have never had such mental anguish,” Clover said of Nevills’ solo trips through difficult rapids. “I waited almost three hours for word of Norm’s success or failure. Failure meant only one thing.”

Filling her journal, Clover’s handwriting became wilder in relation to that day’s events. “We are right out here waging the biggest fight that one can ever wage and getting a big kick out of it,” she scribbled after Cataract Canyon.

The river was more than a mode of travel. Its water was for bathing and laundering; for drinking, but only after its silt had settled; and for a relaxing swim before bed. A beaver once chased after Jotter as she bathed, and one evening a bobcat wandered into camp. Deer and geese became dinner after Atkinson shot them with his rifle; even wild burros began to look tasty as the journey wore on.

Clover conceded it was hard to focus on “mere plants” when fighting a river she alternately described as “the raging devil roar,” “exhilarating” and “thrilling horror.”

“We have all decided that we wanted to come,” she assured herself. “My chief hope is that nothing I may do will hinder the success of the trip.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Graduate student Lois Jotter.

-

-

Chapter 5 “I Would Prefer a Man”

Elzada Clover was committed to her research and her place at Michigan; it was her scientific expertise and personal dignity that attracted Jotter to the trip. “She wanted to do nothing that would discredit the University of Michigan,” Jotter recalled decades after the trip. “And that is what governed all of her activities, in whatever she did.”

The Botany Department did not always return Clover’s respect. Three months before she left Ann Arbor for the Nevills Expedition, the department’s executive committee had refused to promote her to a faculty position more permanent than instructor. She was the lone woman in the department.

Outside of traditional female fields such as education and nursing, few women held regular U-M faculty positions in the 1930s.

“Elzada isn’t wanted because she is a woman,” Bartlett, the department chair, confided to his diary, “although she has been unusually successful as a teacher of the younger students, and we need her precisely for that.”

Bartlett himself wanted Clover to succeed, even if it meant losing her. When he saw other institutions advertising for botanists, he would recommend Clover. The responses were blunt: “I would prefer a man,” wrote an official from the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The gender line was drawn along the Colorado, too. Bathing was segregated (“men upstream, ladies downstream”). The women took care to apply face powder, rouge and lipstick each morning. They also prepared all the meals, washed dishes, mended clothes, and tended to scrapes and bruises.

“The men depend on Lois and me for so many little things. Mirrors, combs, finding shirts, first aid, etc.,” Clover wrote. “Just as men always have since Adam.”

Unwritten rules about propriety became more relaxed with time spent together. At the start of the trip the women changed clothes while still wrapped in their bedrolls. When that became tiresome, they simply asked the men to turn their backs. At the same time, the men often worked only in their underwear, as temperatures rose above 100 degrees and waves drenched them.

“It seems very informal but there’s absolutely no feeling of indecency,” Clover wrote. “People who have not fought with such elements can’t realize how petty and trivial are the things two-thirds of us do in civilization.”

That did not mean, however, that all was civilized on the river.

-

Chapter 6 “I Am Ashamed of Them”

Tension and friction are frequent companions when individuals spend endless days and nights together. Add to that physical danger and uncertainty, and the atmosphere can become toxic.

As the expedition’s leaders, Clover and Norman Nevills, the river guide, made the decisions – whether to run rapids or portage around them; where and when to camp at night; who wasn’t following safety rules. The four younger members soon began to bridle and complain. They distanced themselves from Clover and Nevills in the lead boat; spent hours whispering about perceived injustices; and took pride in calling themselves the Gripers.

The teamwork crucial to surviving the Colorado was at stake. Clover vented to her diary. “It is the most miserable feeling in the world to know that something is wrong and not to know just what or why.”

She fingered Eugene Atkinson, one of her graduate students, as the source of discontent; he was arrogant and whiny, complaining about everything and openly questioning Nevills’ river skills. “Gene is the vicious member trying to be an agitator and imagining he is so superior to Norm, who has had years of boating experience.”

Nevills himself had little use for Atkinson, who had managed to lose an oar and a life preserver. After a day of bucking 20-foot rapids, the expedition leader took to his journal. “The women are standing up beautifully so far. Atkinson is getting some of the sneer out of him and beginning to realize what really big water can do.”

In return, Atkinson believed the leaders held inflated views of themselves and the expedition. “One of them suggested the Smithsonian would want one of our boats, to place next to Lindbergh’s plane. This was so ridiculous that I told them the Smithsonian would certainly make room for all our boats by removing Lindbergh’s plane,” Atkinson said later.

It didn’t help that Jotter was siding with her fellow graduate assistant, although with less venom. “Elzie is eating it up,” she confided in a letter to a friend. “Makes comments like the eyes and ears of the world being upon us, this is as important as Lindberg (sic) and the Byrd exped. – oh me, I’ll tell you more when I see you.”

The muttering and sniping at first seemed silly, but soon left Clover feeling embarrassed and humiliated. She was mindful that she, and her students, represented the University of Michigan. “They are so immature that they don’t realize that they could easily ruin an expedition or at least ruin its reputation. …I am very much ashamed of them but I chose them, so have nothing to say.”

Nevills had the final word. Halfway through the trip, during a layover at Lee’s Ferry, he put an end to the griping: Atkinson was done. It fell to Clover to tell her assistant he was returning to Ann Arbor.

Nevills wrote: “I think Elzada is the best man in the bunch.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Gene Atkinson with a goose he killed in Stillwater Canyon.

-

-

Chapter 7 A Great but Unkind River

Overall the trip took 43 days – 36 on the river – with the final weeks providing smoother water, greater camaraderie and much-improved morale. “We have a fine bunch now,” Clover wrote. Of the earlier friction with Jotter, “we are trying to forgive and forget that.”

The expedition rode out dozens more rapids, taunted and trapped rattlesnakes, and climbed 3 miles up the canyon to visit an ancient giant sloth cave, where petrified dung provided evidence of the extinct animals’ diet (yucca, beargrass, senna, chapparal).

Throughout the journey, the group made frequent stops to allow the women to collect specimens. Maintaining a separate journal for scientific work, Clover and Jotter measured and recorded their findings. “Completed col. and photo of mesquite and Acacia Greggii, and a close-up of the latter. …Upper part of talus has Yucca, Agave utahensis, Opuntia basilaris, O. Engelmannii, and E. fendleri, E. Engelmannii and Ferocactus acanthodes.”

Clover’s research took so much time it delayed the expedition, prompting nationwide worries and an air search of the canyon by the Coast Guard. The pilots dropped notes that read: “We are U.S. Coast Guard plane searching for a party of six U. of Michigan geologists reportedly late at Lee’s Ferry. If you are they, lie down all in a row, and then stand up. If in need of food, sit up. If members of party are all OK, extend arms horizontally. It is imperative that we know who you are, so identify yourself by first signal first.”

Clover and others found it amusing, and signaled all was well. In fact, she wrote, the trip was one of the finest experiences of her life. She and her crewmates passed through the majesty of the Grand Canyon and places with names like Elves Chasm, Hermit Rapids, Vasey’s Paradise and Lava Falls.

“It is impossible to describe the beauty of the moon creeping down the canyon walls, leaving light and deep shadows,” she wrote. “Lord, what country. It is so wonderful.”

There came a point when the expedition arrived at the rapids where Glen and Bessie Hyde, the honeymooners of 1928, were believed to have drowned. It was sobering to Clover.

“Mrs. Hyde was a little thing weighing only 90 pounds. She was afraid of the river. Makes me almost ashamed to enjoy it so much,” Clover wrote. “It’s a great river with a hundred personalities, but it is not kind.”

Those personalities included dozens of diverse areas for collecting plants. Sun-scarred canyon walls provided scrubby specimens, whereas rock formations amidst seeping springs and waterfalls produced tropical-like flora. Clover and Jotter discovered plants scattered in spasms, driven downstream by floods and high water. Other plants clung tenuously to high ledges, having taken root after becoming airborne on canyon winds.

“Here is a case where drought vies with flood waters in exterminating plants struggling for existence in a trying situation,” they later wrote in a scientific paper. Their research would become the first and only systematic botanical survey of the river prior to damming that would significantly alter, and often destroy, plant life in later decades.

Clover and her graduate assistant would identify four new species of cactus and publish their discoveries: Grand Canyon claret cup (Echinocereus canyonensis), with its reddish-purple flower; small flower fishhook cactus (Sclerocactus parviflorus), with its curved spines; strawberry hedgehog cactus (Echinocereus decumbens); and an elongated variety of beavertail prickly pear (Opuntia longiareolata).

When the expedition reached Nevada’s Boulder City and Boulder Dam – the massive new barrier that had yet to be christened Hoover Dam – the trip was over. Reporters swarmed the U-M women, now pioneers and front-page news. Well-wishers pushed for photographs, autographs and stories. When Clover sought refuge in a beauty parlor, cameramen invaded the salon; when she dined alone at a restaurant, reporters hovered at a nearby table. “They have been trailing me all day for a story.”

She was tired of the attention, and wanted back on the river. The expedition’s three tiny boats were empty and moored. She and Nevills, a river runner who had opened her eyes to the Colorado, made plans to reunite the following summer for another river trip.

“God, if only I can wait that long. I’m so lonely for it now I can hardly stand it,” she wrote. “Could scarcely keep from crying as I stood on the boats today and felt them rising up and down with the waves.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Glen and Bessie Hyde began their 1928 honeymoon on the Colorado River. -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Grand Canyon claret cup specimen collected by Clover and held by the Smithsonian Institution.Image: National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution. -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Small flower fishhook cactus specimen collected by Clover and held by the Smithsonian Institution.Image: National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution.

-

-

Chapter 8 Epilogue

Lois Jotter went on to earn her U-M doctorate, become Lois Jotter Cutter, and raise a family. Following her husband’s death in 1962, she joined the botany faculty at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and taught nearly 20 years. When she died in May 2013 at age 99, she was the last surviving member of the Nevills Expedition.

Eugene Atkinson never again saw his river colleagues. He told an interviewer years later that he left the Colorado “completely fed up with Norm Nevills’ publicity-seeking expedition.” He died in 1994 at age 81.

Norm Nevills is widely credited with opening up the Colorado River to commercial rafting due to the success of the 1938 expedition. When he died in a 1949 plane crash, Nevills was 42. The Wen, the boat he piloted with Clover alongside, is on permanent display at the visitor center of Grand Canyon National Park.

Elzada Clover spent her entire career at U-M, slowly climbing the faculty ranks to become a full professor in 1960. Over her career she identified nearly 50 species of cacti, begonia, mosses and other plants in the United States, Guatemala and Mexico. She retired in 1967, and died 13 years later. In 2007, the University established the Elzada U. Clover Collegiate Professorship in the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts.

The cactus she collected along the Colorado and shipped to Ann Arbor became the foundation of the desert collections at what is today’s Matthaei Botanical Gardens. In thanking Clover, the Board of Regents called the plants “her continuing monument.”

This article was drawn chiefly from The Wen, the Botany, and the Mexican Hat by William Cook; Elzada U. Clover Papers and Harley Harris Bartlett Papers, Bentley Historical Library; Lois Jotter Cutter Collection, Cline Library, Northern Arizona University; High Wide And Handsome: The River Journals of Norman D. Nevills by Roy Webb; “Cacti of the Canyon of the Colorado River and Tributaries,” by Elzada U. Clover and Lois Jotter, Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club; and “Floristic Studies in the Canyon of the Colorado and Tributaries,” by Elzada U. Clover and Lois Jotter, American Midland Naturalist.