Two Against Football

By James Tobin

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

[A new stadium] will be a permanent concession, set in concrete for years to come, to the notion that college is nothing more than a Roman holiday.– Neil Staebler

-

Chapter 1 Yost’s New Project

The University of Michigan Chimes was a little student weekly that published sketches, essays, poems, and literary reviews. Nobody paid much attention to it, at least not until a senior named Neil Staebler took over as editor in the autumn of 1925.

Staebler had grown up in Ann Arbor at a time when the biggest man in town—the biggest man in the state—was the football coach Fielding H. Yost.

In 1905, the year Staebler was born, the Yostmen—as the Michigan Daily liked to call the varsity—had an off year, for Yost. They went 12-1. (From 1901 to 1904 the team’s record had been 43-0-1.) In the 20 years of Staebler’s youth, Yost’s teams tied nine games, lost 29, and won 114. Yost was widely seen not only as a great coach but also as a great man, a builder of character in the young and a champion of athletics for all—all men, anyway…well, all white men. (The son of a Confederate soldier, Yost allowed only a small handful of black athletes to play for Michigan, and only in sports less conspicuous than football.)

Now Yost was also Michigan’s athletic director. In the fall of 1925, at the age of 54, he was working crazy hours and running all over the state in pursuit of a huge new achievement.

Most people in town were rooting for him. Neil Staebler was not.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The football program for the 1925 Ohio State game at Ferry Field, published in the midst of Yost’s campaign for a new stadium.Image: Image available online in the Art of Football exhibit and in the U-M Athletic Department collection, Bentley Historical Library.Chapter 2 “Tickets! Tickets!”

Americans had gone nuts for college football, and a stadium race was under way. Colossal palaces had been built or planned at Yale (70,896 seats), Ohio State (75,000), and Illinois (92,000), among others.

Michigan students, Michigan alumni and people with no direct connection to the school mobbed home games. In 1922, half the entire student body of 11,000 went to the Ohio State game—in Columbus. When Michigan played at home, special trains discharged carloads of fans from across the Midwest, and every Ann Arbor bedroom was crammed with extra cots, bunks and blankets.

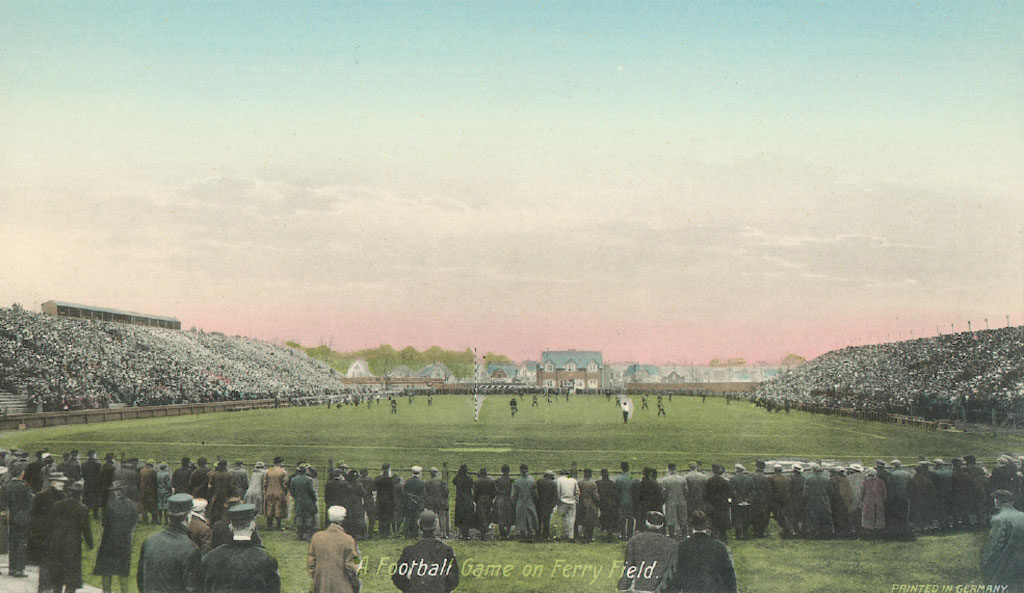

But Michigan’s Ferry Field, beloved as it was, held only 37,000 spectators in the early 1920s. The demand for seats was estimated at twice that number or more, and a cry was rising for some solution to the uproarious demand for tickets.

At first the University’s governing Board of Regents (some of whom requested up to 60 tickets a game for family and friends) said no to any new stadium; the cost would be too high. Maybe more stands could be built at Ferry to meet the need. They were—and the demand for tickets only grew.

When the Wolverines compiled an 8-0 record in 1923 and were named national champions, powerful alumni began to call for construction of a new stadium to seat up to 100,000 fans.

When the Wolverines compiled an 8-0 record in 1923 and were named national champions, powerful alumni began to call for construction of a new stadium to seat up to 100,000 fans.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

A student artist’s caricature of Yost, already known as one of football’s “grand old men.” He was also a political power in Michigan.Chapter 3 Yost on the Stump

Coach Yost had an idea to defuse the regents’ fears about the prohibitive cost of a new stadium. To fund construction, he would sell 20-year bonds with a guarantee of two season tickets to every buyer. No student would pay extra. No one would be asked for a donation. No new taxes would be levied. And Yost said football revenue would pay for a grand new complex for other sports and intramurals.

It was brilliant. Alumni were delighted. Students were ecstatic. Marion LeRoy Burton, the University’s popular president and a great friend of Yost, appeared to be on board. The Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics (where Yost enjoyed a strong majority of alumni and students) sent it up to the regents.

Then, early in 1925, President Burton died of heart disease at the age of only 50.

His interim replacement was the scholarly Alfred Henry Lloyd, dean of the graduate school, a professor of philosophy. Dean Lloyd was not the friend of football or Fielding Yost that President Burton had been, and he called a screeching halt to the stadium charge. He appointed a faculty committee headed by Edmund Day, dean of the School of Business Administration, to study the entire question of athletics at Michigan. After the Day committee had studied and deliberated, Lloyd said, a thoughtful decision about any new football stadium might be made.

At this, Yost went into overdrive. All that spring and summer he gave speeches from Monroe to Marquette to Kalamazoo, to Rotary Clubs, Kiwanis Clubs, Chambers of Commerce. On the faculty there might be snooty naysayers, but among outstate alumni and just plain fans, he had thousands of allies. Michigan was behind in the stadium race. The state had to compete.

“Whether the stadium is crammed to capacity or almost empty,” he told audiences, “the desire to win by students and alumni is present just the same. It will be a sad day for the youth of America when they no longer want to win. They will become a limp, listless set of boys and girls.”

Yost came off the stump to start the 1925 season. The Day committee met, asked questions, met some more. The regents appeared to be coming around. “You made a mistake when you went in for football instead of the law,” Regent James O. Murfin wrote to Yost. “As an advocate either orally or in writing you have no equal.”

That was when Neil Staebler, 20 years old, became the editor of Chimes.

As his classmates marched down to games at Ferry Field, waiting and watching for what now seemed all but inevitable—an announcement that the Yostmen would soon play in America’s greatest stadium—Staebler got in touch with Robert Cooley Angell, a sociology professor who was barely out of graduate school, one of the youngest members of the faculty.

Knowing the impossibly long odds, and the poisonous treatment they would get from their friends, Staebler and Cooley decided to object.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Robert Cooley Angell in his early days as an assistant professor of sociology at Michigan.Chapter 4 Michigan Royalty

Robert Cooley Angell was a reluctant recruit to Neil Staebler’s hopeless cause.

If there was such a thing as U-M royalty, no one had a better claim to it. Angell’s paternal grandfather was James Burrill Angell, Michigan’s president from 1871 to 1909. His maternal grandfather was Thomas McIntyre Cooley, a great dean of the Law School. His father was Alexis Caswell Angell, a Michigan law professor. One of his uncles was the Michigan sociologist Charles Horton Cooley; another was James Rowland Angell, then president of Yale. In 1919, that Angell had almost been appointed president of Michigan—until he stated plainly that he thought intercollegiate athletics should be done away with.

This new Angell was anything but a musty-headed old professor looking down his nose at students’ fun. He was barely 25 years old. Only a few years earlier he had been sports editor of the Michigan Daily. He had played varsity tennis for Michigan and was “a thorough believer in athletics.” And he knew the student mind better than anyone. His doctoral dissertation was about student social structures in Ann Arbor, soon to be published as The Campus: A Study of Undergraduate Life in the Contemporary American University.

In the Daily and the Ann Arbor News, he already had spoken out against the excesses of college football, saying “the complete abolition of intercollegiate athletics” would be “the quickest solution to the problem.”

For that, he said, he had been “pronounced inhuman, devoid of emotion, incapable of feeling thrills and disgustingly academic.” So many people had stopped him to say, “What’s the big idea?” that he had resolved to keep his mouth shut on the subject.

But Neil Staebler persuaded him to take one more swing at big-time college football.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Ferry Field was beloved by a generation of fans. But despite the addition of more and more seats, by the 1920s it could no longer meet the soaring demand for more tickets.Chapter 5 “Back to Fundamentals”

Angell sat down to craft a careful essay in the vein of an introductory lecture in sociology.

“The easiest way to approach the problem at hand,” he began, “is to go back to fundamentals.

“At Ann Arbor is an institution called a University. What does this mean? It means first and foremost that here is a social structure dedicated to the improvement of human life through the acquisition of knowledge.”

No one would dispute that statement, he said—not even the fiercest Michigan fan.

So the logical question about football should be: “Does the present system of intercollegiate football promote or discourage the acquisition of knowledge?”

If it promoted knowledge, he said, then everyone should rally around Yost and build a bigger stadium.

But did it?

The logical question about football should be: “Does the present system of intercollegiate football promote or discourage the acquisition of knowledge?”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

In the fall of 1925, as Neil Staebler and Robert Angell argued against a new stadium, the comedy star Harold Lloyd was appearing at Ann Arbor’s Arcade Theater as “The Freshman,” an eager beaver determined to win love and popularity on his college’s football team.Image: The Michigan DailyChapter 6 “Intellectual Sins”

As for the players themselves, Angell said, only a few did more in class than maintain their eligibility. Nearly all their time and energy went to the sport. “Their diplomas cover a multitude of intellectual sins.”

But the athletes were only “a few drops in the bucket of university life.” What harm could football possibly do to the thousands of other students who simply showed up to cheer?

Well, said Angell, every autumn, football became a kind of addiction for students, “many but mildly, some seriously.” The sport seized “a monopoly of undergraduate conversation… A scientific theory or a piece of fine poetry has not a chance to squeeze in edgewise.

“Around the dinner table, in one another’s rooms, walking to and from classes, the chief topic for discussion is the team’s make-up, its powers, its chances for the next game…”

And all this talk hauled students’ attention away from the real purpose of college. Their focus was not the mind but the muscles, not clashing ideas but clashing bodies on a field of battle.

“The worship of the man who can throw a forward pass thirty yards…is not likely to turn…impressionable youngsters towards the fascinating problems of science, history and literature.”

And beyond the campuses, Angell said, big-time football was exerting “a subtle degrading influence” on the public’s opinion of education.

Because of press attention to football, he said, now “the ‘college man’ is proverbially an individual with little to do but drink, make love, and cheer for the team.” That influence, in turn, was attracting “pleasure seekers with no intellectual interest”—and “how can we hope to stimulate a love of knowledge in students like this?

“I enjoy watching a football game almost as much as the next man,” he said. “Time was when I enjoyed it more. But that does not alter the unmistakable fact that students could still be allowed this pleasure without the contests becoming a great public spectacle. That is what turns a fine thing into a degenerating one. The university has certainly no duty to furnish public entertainment to its own detriment.”

And “all the harmful conditions which I have suggested as flowing from intercollegiate football in its present form would be made worse if Michigan were to build a larger stadium.

“A university, if it is to be a university at all, must preserve its intellectual standards at all costs; to cater slavishly to the deserts of the general public is but to invite destruction.”

When Fielding Yost read that, he saw red.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Yost with Harry Kipke, the last great Michigan star to play at Ferry Field. Kipke soon would coach the Wolverines in Michigan Stadium.Chapter 7 “What are Objections?”

What infuriated Yost was that Angell was biting the hand that had fed him.

“This same Robert C. Angell is a former member of the Varsity Tennis Team,” Yost fumed in a letter to the press. “He played with racquets and tennis balls purchased by the Athletic Association. He played on tennis courts built and maintained by the Athletic Association. He went on out-of-town trips and had all his expenses paid by the Athletic Association. He wears the ‘M’ Hat and ‘M’ Sweater awards he received from the Athletic Association. The money for all these items was taken from the earnings made by these horrible football men.”

The Daily’s editors rushed to Yost’s side.

“What are the objections?” the paper’s lead editorial asked. Angell was attacking intercollegiate football as a whole, they said, not the proposal for a bigger stadium. And that was plain nuts, since “football is here to stay.”

In that case, they said, “one finds it hard to understand how a stadium of 75,000 seats will have a more detrimental effect on the student body than one of 45,000.”

If there were any good reasons not to build a bigger stadium, the Daily taunted, the critics should state them, “but the mere fact that freshmen idolize the Varsity man is hardly a valid objection.”

The Daily’s volley was published on Tuesday, October 13, 1925, two days after Robert Angell’s essay in the Chimes.

That gave Neil Staebler the rest of the week to polish his own arguments for the Chimes’ next assault on the stadium plan.

Angell had opened the argument. But he spoke as a faculty member. That left out a lot that Staebler wanted to say from a student’s point of view. If the Daily wanted to hear more objections, he was happy to oblige.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Earlier editors of the Michigan Daily had been skeptical about the need for a new stadium, but by 1925-26, the student paper was all for Yost’s project.Image: The Michigan DailyChapter 8 “What College Should Be”

On October 20, the Chimes carried Staebler’s own essay, titled “Stadiumania.”

He began by saying the stadium debate amounted to competing theories of “what college should be.”

Opponents of a giant stadium, he wrote, “conceive college to be primarily a place for those who are interested in study, a place in which distraction shall be minimized.”

The other view, “sponsored by convivial alumni and accepted by what is unquestionably a majority of students,” was that “college is a place to acquire a minimum amount of knowledge and technical skill required to earn a fair living, at a minimum sacrifice of amusement and pleasure.”

Construction of a giant stadium would be a monumental endorsement of the latter view, he said. It would be “a dedication of Michigan to the proposition that sport—which is the representative college amusement—deserves even a greater place in the minds and lives of students, alumni and the public than it now occupies.”

Angell had attacked the stadium plan on academic grounds, Staebler said, but he opposed it more for “its deleterious social influence.”

He didn’t mean gambling, he said, or drinking, or “the other debaucheries so common during football season.”

What really troubled him was the sheer fatuousness of student culture under the influence of football—“the fellows that boast about their beer parties and hot times and that seem to be hangers-on in the University only for the amusement they derive…a disgustingly Babbittish crowd to whom the true purpose of college is as incomprehensible as the Dialogues of Plato.”

So what did that have to do with a bigger stadium?

Consider basketball, Staebler said. Just as exciting a game, but played in a small arena, it generated none of the obsessive chatter or boorish behavior that football did. If the size of the football phenomenon had been capped early on, it “would not have grown into the parasite it has become.”

A stadium twice the size of Ferry Field would double the trouble—twice the monopoly on daily conversation; twice the pre- and post-game brawls; twice the publicity and its attendant pressure for winning above all.

Finally, he said, “Michigan, by building a larger stadium, will be setting its stamp of approval upon an institution and a set of conditions inimical to its own best interests; it will be a permanent concession, set in concrete for years to come, to the notion that college is nothing more than a Roman holiday.”

* * *

In all, Staebler published more than a dozen substantial pieces by various authors on the stadium question. Most were against a vast new football palace; several wrote in favor. The series concluded in January 1926, just before the Day committee released its report on athletics at Michigan.

The committee said Michigan should dampen the fierce emphasis on winning; reduce the imbalance between intercollegiate and intramural sports; and put more faculty on the Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics. The University was “an institution of higher learning, not a purveyor of popular entertainment,” the committee said. “Intercollegiate athletics seem to have grown out of all proportion to the importance of the purposes which they serve.”

But few people paid attention to any of that. Instead, headlines trumpeted the Committee’s grudging admission that there might as well be a new stadium of perhaps 60,000 seats.

The regents soon approved the report, saying “a stadium of seventy thousand would not be objectionable.”

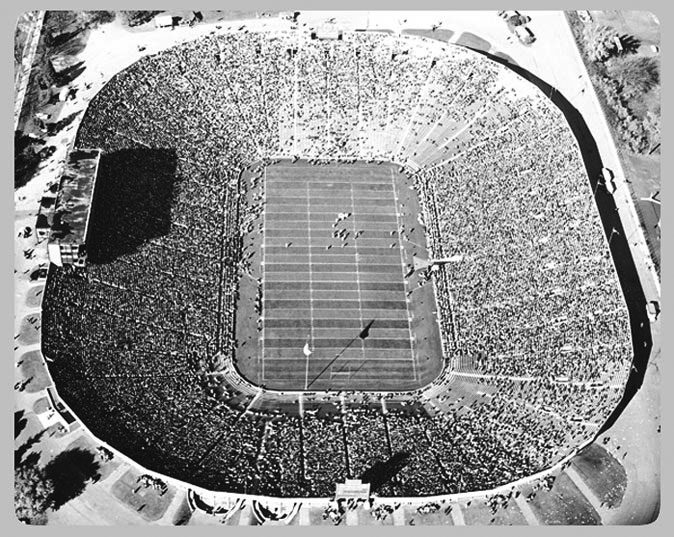

A year and a half later, on October 1, 1927, with 72,000 seats, Michigan Stadium hosted its first game, a 33-0 victory against Ohio Wesleyan—though heavy rains kept the day’s attendance to under 40,000. The official dedication was held three weeks later on a fine Saturday afternoon when the Wolverines defeated Ohio State, 21-0.

Over the years many more seats were added—13,752 in 1928; 12,187 in 1949; 3,762 in 1973; 1,500 in 1992; 5,000 in 1998; and (after 1,300 seats were lost in 2008), 3,700 in 2010. With an official capacity of 109,901, it is the largest football stadium in the United States.

Intercollegiate athletics seem to have grown out of all proportion to the importance of the purposes which they serve.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

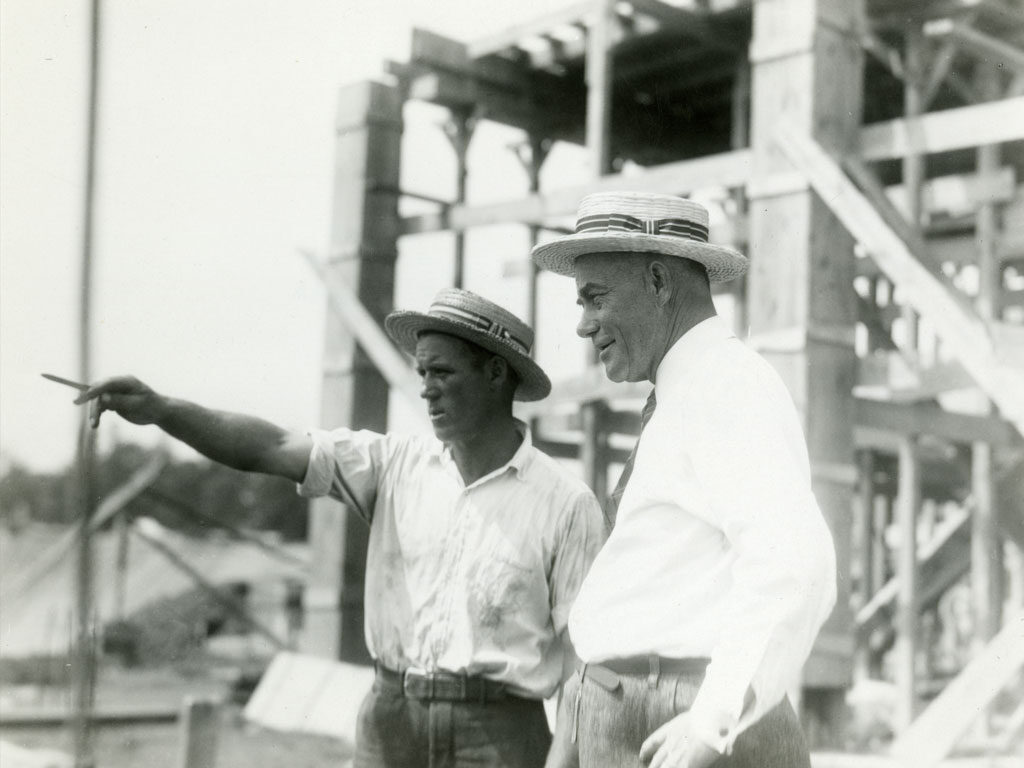

Yost at the dedication of Michigan Stadium on October 22, 1927. (Michigan beat Ohio State, 21-0.)Chapter 9 Epilogue

Much fun was made of Robert Angell when, shortly after his essay appeared in the Chimes, he was spotted at a Michigan football game. But he had one consolation prize: In 1926 he was appointed to the Board in Control of Intercollegiate Athletics, and thus enjoyed a small measure of influence over U-M athletic policy.

Angell went on to become one of the most prominent sociologists of his generation, publishing several notable books and serving as president of the American Sociological Association. At Michigan he was chair of the Sociology Department and helped to found the Honors Program, which he directed for several years. He retired in 1969—though he continued to teach for a number of years—and died in 1984.

Fielding Yost was not at the Wolverines’ helm for their first season in the new stadium. He had stepped down as coach just before the season began, saying he simply had too much to do as athletic director. He retired as A.D. in 1941 and died in 1946, the most honored figure in the history of Michigan sports.

Neil Staebler graduated from Michigan just as Yost’s architects and engineers were drawing plans for what would much later be called “the Big House.” He was the last editor of the Chimes, which folded the following year. He earned a law degree, joined his family’s business in Ann Arbor, then went into politics.

After World War II he became the power-behind-the-throne to four major Michigan Democrats—G. Mennen Williams, who served a record seven terms as governor; Gov. John Swainson; Sen. Patrick McNamara; and Sen. Phil Hart. (Like Staebler, all but Swainson were Michigan alumni.)

In 1962, Staebler was elected congressman-at-large from Michigan. In 1964 he made an unsuccessful run for governor against the popular Republican incumbent, George Romney.

He was for many years the grand old man of Michigan Democrats, serving a long tenure as Democratic National Committeeman. He lived and worked in Ann Arbor until his death in 2000.

And he was an enthusiastic fan of Michigan football, holding season tickets for decades.

Once, at the peak of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, Staebler wrote to a Michigan faculty member of the 1920s about their mutual support for a controversial student organization called the Negro-Caucasian Club.

The fight for black equality had been one thing, Staebler remarked, but “no present protest has approached the obloquy that the community poured on us for trying to subvert football.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The prototypical alumnus, captured on the cover of the U-M football program of November 6, 1926.Image: Available online at the Art of Football exhibit and in the U-M Athletic Department records, Bentley Historical Library.

-

-

Chapter 10 Resources

- The papers of Robert Cooley Angell, Neil Staebler and Fielding Harris Yost are housed at the Bentley Historical Library.

- The extensive holdings of the Bentley Historical Library include a U-M Athletics history and a wealth of Athletic Department archives.