The Lost Campus

By James Tobin

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

My memories of the place are sweet, and so many things that formed those memories have been altered.– Arthur Miller (LSA, 1938)

-

Chapter 1 Ghosts

The great American playwright Arthur Miller graduated from Michigan in 1938. When he returned in 1953—his first visit in 15 years—he was dismayed by evidence of a changed campus, especially the massive and unfamiliar new residence halls—Stockwell Hall, Alice Lloyd Hall, West Quadrangle, East Quadrangle.

“My memories of the place are sweet,” he wrote, “and so many things that formed those memories have been altered. There are buildings now where I remembered lawn and trees. And yes, I told myself as I resented these intrusions, in the Thirties we were all the time calling for these dormitories and they are finally built.”

Each cadre of students at Michigan goes through Miller’s experience. It began with graduates of the 1850s who came back after the Civil War and were surprised and a little wistful to find no cows grazing in the Diag. Every alumnus carries a cherished memory of Michigan—then returns in 20 years and realizes that “my Michigan” is hard to find among the new construction of someone else’s Michigan.

Those old Michigans make up a ghostly terrain we might call the Lost Campus. Here are a few reminders.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

In this section of a panoramic map of Ann Arbor in 1880, the Cat Hole with its pond is plainly visible at center right.Chapter 2 The Cat Hole

In the earliest times, the University needed no more space than the 40 acres bounded by State Street and the three University Avenues. But when the campus began to grow, it ran into a natural barrier to the northeast.

Students called it the Cat Hole—a wild, marshy bowl with a meager pond at the bottom. (Why it was named for cats remains a mystery.)

In the 1870s, sophomores carried freshmen to the Cat Hole for dunking in the pond. In winter students flocked there for skating and coasting down the slopes.

An old woman named Johnson had a cabin overlooking the pond. She would tell students their fortunes from a deck of cards.

On a bird’s-eye map of Ann Arbor in 1880, the Cat Hole’s pond is clearly visible. The only University building to the east of it is the Detroit Observatory up on its lonely hill. The map shows the long, broad ravine that leads north from the pond—roughly the path that Glen Street now takes past Angelo’s Restaurant down toward the shallow valley of the Huron River.

In time, the Cat Hole filled up with piles of brush and debris, then disappeared altogether under bulldozers.

But when workers dug down to build a foundation for the parking structure behind the Power Center for the Performing Arts, they found the same underground sources of water that once fed the Cat Hole’s pond.

In the 1870s, sophomores carried freshmen to the Cat Hole for dunking in the pond. In winter students flocked there for skating and coasting down the slopes.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

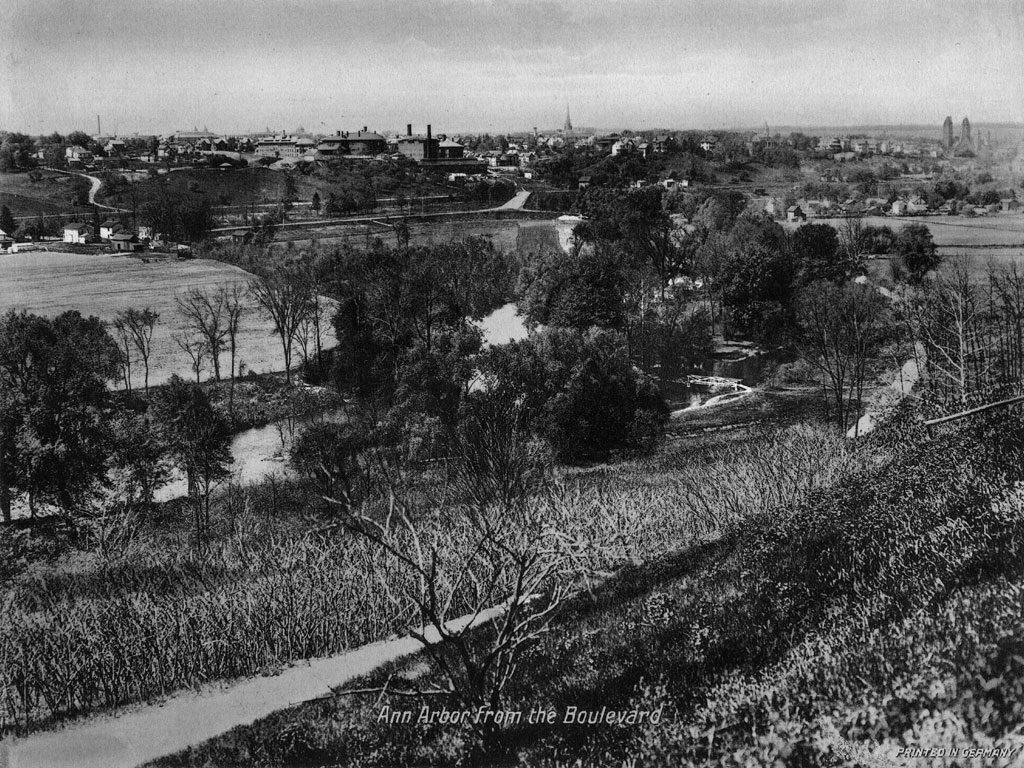

A postcard view of Ann Arbor and the Huron River valley from the summit of the Boulevard, about 1920. The brick-red buildings on the horizon at left are the Catherine Street Hospitals, predecessors of University Hospital (Old Main). The church at far right is St. Thomas the Apostle, on North State Street.Chapter 3 The Boulevard

From the mid-1800s to about the time of World War I, before the village and the campus spread outward in all directions, students liked to hike out of town to escape the pressure of classes and study. One of their favorite destinations was a twisting dirt road that ran from the Huron River up a slope to the summit of the ridge to the north.

On some maps the name of the road was Cedar Bend Avenue, but everyone called it “The Boulevard.”

The Boulevard had a lower leg closer to the campus; it took a meandering path from Observatory Street to the Huron. But it was the upper leg, north of the river, that drew the more ambitious hikers.

“It seems rather pretentious to call it a Boulevard,” Judge Noah Cheever wrote at the turn of the 20th century, “still it makes up in beauty for what it lacks in extent….As many as nine hundred have been counted passing over this boulevard on a beautiful spring or fall day.”

It was a strenuous climb in Sunday clothes, but the reward was a series of lovely views of the campus and town. Cheever described the terrain in the Michigan Alumnus:

“The road bends around the ravines and the views… are very beautiful and impressive. Almost every rod of the road presents some new scenery and some features of interest and beauty. There is an island in the river near the Boulevard known as Picnic Island which adds much to the beauty of the river and the scenery upon this drive. … It is…well to stop on the high ground just at the last bend before reaching Broadway… This view of the Huron valley, Picnic Island, the University hospitals and north portion of the city and a large portion of the country west and northwest, including the Huron valley, is very fine indeed.”

Old photographs and postcards show us what the hikers saw from the top. In the postcard shown here, from about 1910, we see in the foreground the farm fields that would become Island and Fuller Parks, with Fuller Road running from east to west toward town. The reddish-brown buildings at center left are part of the medical complex called the Catherine Street Hospitals. Just to the left of the hospitals, on the horizon, the dome of University Hall juts up about where Angell Hall stands now, and at far right stands St. Thomas the Apostle Catholic Church.

A 1905 graduate named Mabel Julia Moorhead treasured her memory of the Boulevard.

“Is it as beautiful now, I wonder?” she wrote 20 years after leaving Ann Arbor. “Those mornings when we planned to go out to see the sun rise—it always rained—and how much more attractive ‘sunrise from the Boulevard’ sounded the night before. But moonlight on the Boulevard! Oh! There was never anything to equal that.”

In the early 1900s the city of Ann Arbor purchased 19.5 acres on the slope and made them the city’s first park, now called the Cedar Bend Nature Area. The old Boulevard was allowed to dwindle into an eroded dirt path, barely visible any more at some points. Oaks and hickories grew tall, obscuring most of the old views, though the prospect from Cedar Bend Drive, the uppermost segment of the old Boulevard, is still, as Judge Cheever said, “very fine indeed.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The Diag outhouse called “Campus Beauty,” about where the Kraus Natural Science Building stands now. The Homeopathic Hospital, fronting on North University, can be seen behind it.Chapter 4 Campus Beauty

Among the Bentley Historical Library’s countless files of historical photographs, there is a special collection gathered by the photographer Sam Sturgis. One folder holds the print shown here. On the back is this inscription, handwritten in pencil: “Campus Beauty.”

The photo shows a stout frame structure that is pretty obviously a community outhouse. It appears to have 14 private compartments—presumably half for men and half for women. Behind it one can see the cupolas of U-M’s old Homeopathic Hospital, which stood on the site of the Kraus Natural Sciences Building until the early 20th century. That, and a horse and wagon, put the time of the photo somewhere around 1900.

The term “Campus Beauty” may have been the actual name by which the structure was known, or it might have been Sam Sturgis’s private joke—the question awaits definitive research. In any case, the photo is rare documentation of an obvious fact: The campus was dotted with outdoor privies for many, many years.

Their demise came on the horizon in 1871, when James Burrill Angell, president of the University of Vermont, said he would accept the Regents’ invitation to take Michigan’s presidency only if they raised their salary offer from $4,000 a year to $4,500— and if they paid for the installation of a toilet in the President’s House. With three children, Angell and his wife, Sarah Caswell Angell, were reluctant to leave the fine president’s house just completed at Vermont without the promise of a toilet in the West.

The Angells’ installation is reputed to be the first flush toilet in Ann Arbor. But it was the 1890s before a sewer system was installed throughout the city and flush toilets became the rule instead of the exception.

Exactly when the last “Campus Beauty” was demolished, no one now remembers.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

In the second Sleepy Hollow, east of Observatory Street, much of the student body masses for Cap Night, circa 1920. Freshmen are seated with their caps on their heads, awaiting the moment when they will toss their caps on a bonfire.Chapter 5 Sleepy Hollow

In the early years of the 20th century, a place called Sleepy Hollow was the setting for the rite of passage called Cap Night, when thousands of students—virtually all the students—gathered in a natural amphitheater in the light of a great bonfire to watch male freshmen turn themselves into sophomores.

Actually, it appears that two natural amphitheaters went by the name Sleepy Hollow. They lay across the street from each other at the north end of Observatory Street.

The first Sleepy Hollow—which held the name for several years after 1905—was at the northern edges of Palmer Field. Imagine you’re walking down the slope from the rear of the Detroit Observatory toward the Palmer tennis courts and track; you’re in Sleepy Hollow, with the rise toward Couzens Hall to the north and the rise toward Alice Lloyd Hall to the east. But in 1905, neither of those buildings was even a twinkle in an architect’s eye. The only substantial building nearby was the Observatory.

By day, in the warm months, Sleepy Hollow was a place where physical education instructors took women students for calisthenics and dancing. Indeed, Professor William J. Hussey, director of the Observatory, objected on grounds of modesty to the city’s plans to extend Huron Avenue through Sleepy Hollow. Passing traffic, he said, would “deprive the girls’ athletic field…of the privacy which is most desirable and without which much of the freedom of the exercises…will be lost, as they are naturally diffident about appearing in public in the gymnasium costumes which make the exercises beneficial.” (The extension was never built as planned, though several streets in the neighborhood were rerouted or obliterated as the medical campus grew.)

Then, every year in early June, came Cap Night.

By custom, all year long, U-M freshmen were made to wear a certain style of gray cap whenever they went outdoors. Forget your cap and you were in for upper-class hazing. It symbolized freshman serfdom in the era when rivalries between the classes were powerful.

On Cap Night, the students marched in a massive parade from State Street to Sleepy Hollow. There they sang Michigan songs, celebrated the year’s triumphs in sports, heard speeches by famous upperclassmen, and finally, in the evening’s climax, watched the freshmen take off their hated caps and hurl them onto a towering bonfire. It was their ritual release into the freedom of sophomore status.

Then, somewhere in the 1910s, for reasons that aren’t clear, Cap Night and the name Sleepy Hollow crossed Observatory to a larger swath of empty land. It lay along the lower leg of the meandering trail called the Boulevard. Today, if you look closely, you can still see the shape of the second Sleepy Hollow under parking structures and medical buildings—a broad half-bowl sloping downward and eastward toward the new Mott Children’s Hospital. It was big enough to accommodate thousands of students and thousands more onlookers, as the few surviving photographs show. The ritual march from Central Campus continued. Afterward, back in town, the movie houses offered free shows.

All this made for strong memories.

“Cap Night at the Hollow stands out as one of the lovely pictures,” recalled an alumna named Mildred Wood, who graduated in 1910, “the light of the huge bonfire reflected on the faces of the crowd on the hills—the songs, dances…”

Evalynn Walker, a graduate of 1916, quite agreed.

“Cap Night, out on the Boulevard,” she said, “was a far more thrilling and impressive spectacle than any stilted formalities could ever hope to make Commencement.”

But by the 1940s Cap Night had faded out, and the second Sleepy Hollow went down under the bulldozers.

Sleepy Hollow was a place where physical education instructors took women students for calisthenics and dancing.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

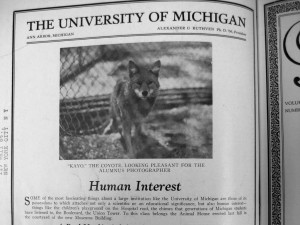

The Animal House, better known as the University’s Zoo.Image: Ruthven Museums, University of Michigan.Chapter 6 The Zoo

Imagine yourself on the footbridge that spans Washtenaw Avenue between the Hill dorms and Central Campus. Look west toward State Street. See the Central Campus Classroom Building, at the northwest corner of North University and Washtenaw Avenue?

That classroom building sits on the site of the University of Michigan’s only zoo.

In the 1920s, U-M zoologists got the idea of displaying living Michigan mammals to the public. So, in the summer of 1929, with money from an anonymous Detroit donor, they erected a fenced-in brick hexagon with a shingled roof, then brought in the first residents—a badger, a red fox, six raccoons, two porcupines, four skunks and two black bears.

The next spring they added space for nine species of Michigan turtles and seven species of Michigan snakes, among them the garter, fox, water, hog-nose and blue racer. (The Eastern Massasauga rattler, the state’s only venomous snake, was not invited.)

The official name was alternately the Mammal House and the Animal House, but most people just called it the Zoo.

It was an early smash, especially with kids. “Occasional checks for one day showed that hundreds of children and adults were coming,” the director of the Museum of Zoology reported in 1930. “Perhaps the pleasure which the crippled children from the University Hospital have taken before the bear cage alone justifies the effort and expense.”

Four-footed residents came and went. One of the two wolverines that Fielding Yost tried to make into a living university mascot apparently was housed there, though it didn’t work out—no surprise, since the wolverine is not native to Michigan, with only one confirmed sighting in 200 years.

By modern zookeeping standards, it was pretty dismal. The mammals had little room to move around, and if their cages were smelly, the reptile quarters were a good deal worse.

People who grew up in Ann Arbor remember the Zoo with mixed feelings. “I always felt sad for the animals because their accommodations were so stark,” said one, “but I loved going to see them.” Many U-M students apparently missed the place altogether. “How on earth did I, and everyone I knew, spend four years in Ann Arbor and never realize there was a University Zoo?” asked a student of the early ‘50s.

In 1962, needing more space, the museum closed the zoo and sent most of its last denizens to a small zoo in upstate Grayling. One or two may have wound up inside the Natural History Museum—stuffed.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

A Michigan coyote in close quarters at the Zoo.Image: Michigan Alumnus, March 1930

“How on earth did I, and everyone I knew, spend four years in Ann Arbor and never realize there was a University Zoo?”

– U-M student in 1950s -