Professor Ford

By Kim Clarke

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

It would give immense satisfaction to both faculty and students of the University to have you as one of our colleagues.– President Robben W. Fleming

-

Chapter 1 Back to Michigan

Jerry Ford was coming home as a foreigner.

The University of Michigan knew him as a star football player, earning three varsity letters and Most Valuable Player honors as a senior in 1934.

He returned to campus as a longtime congressman representing Grand Rapids, as vice president to embattled President Richard M. Nixon, and as the 38th president of the United States. He designated U-M as the repository for his papers, and used Crisler Arena to kick off his re-election campaign in 1976 in hopes of securing the presidency on his own terms.

But he had never stepped on campus bearing the title he did in the spring of 1977: Professor Gerald R. Ford.

Awaiting him were hundreds of undergraduate and graduate students.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

With the president's voice lost to campaigning, first lady Betty Ford reads his concession speech after losing to Jimmy Carter.Image: Gerald R. Ford LIbraryChapter 2 “What Are Your Plans?”

Months earlier, on the morning of November 3, 1976, President Gerald R. Ford sent a telegram to Jimmy Carter. “It is apparent now that you have won our long and intense struggle for the Presidency. I congratulate you on your victory.”

On the same day, Political Science Professor George Grassmuck wrote a letter to U-M President Robben W. Fleming. “To lose a presidential election is to lose much, and the more so for an incumbent. Defeated candidates are weary and have little respite before they face that early and urged media question, ‘What are your plans for next year, Mr. President?’”

Grassmuck, Fleming and others wanted Ford’s plans to include teaching at the University of Michigan. Few American presidents had ventured into the classroom after the White House, and here was an opportunity to persuade Ford to come to Ann Arbor.

For several weeks after the election, a small team of professors from the Political Science Department and the Institute of Public Policy Studies worked to create a role for Ford and lobby members of his administration. They knew they were competing with law firms, corporate boards of directors, and other universities, all keen for the presence of a former president.

“We should be eager to have you on campus for as long or as often as you wish. This might range from visits of a few days to visits of a whole academic year, with any kind of time in between those two extremes,” Fleming wrote in early December when inviting Ford to U-M.

“It would give immense satisfaction to both faculty and students of the University to have you as one of our colleagues.”

Fleming again lobbied Ford when the president came to campus two weeks later for winter commencement, where first lady Betty Ford was receiving an honorary degree. “I hope we have made it abundantly clear,” he told Ford, “how anxious we are to have you join us on some mutually agreeable basis, so I shall be anxious to do anything I can to further the cause.”

-

Chapter 3 “Eager Anticipation”

Ford’s aides told U-M officials the president would make no commitment until leaving the Oval Office on Jan. 20, 1977. Still, Ford’s chief of staff, Dick Cheney, indicated U-M “stands high on the list” for the president’s post-White House life.

“Cheney said Mr. Ford believes he ought not to attempt to shoulder detailed academic and class responsibilities. His national role as a former President will not permit that,” Grassmuck reported after meeting with Cheney. A scholar of the American presidency who had worked as an executive assistant in Richard Nixon’s White House, Grassmuck also noted: “Cheney did graduate work in political science at the University of Wisconsin, so he knows our discipline and its workings.”

Harold Jacobson, chairman of the Political Science Department, and others met with Ford in the White House a day before Jimmy Carter’s swearing in to sharpen details for a campus stay. An ideal time would be early April, before students faced the end of classes and final exams. Jacobson told Ford, in a follow-up letter, that anticipation was growing on campus.

“Both the Michigan Daily and the Ann Arbor News have enthusiastically endorsed your prospective appointment as an adjunct professor of political science. I do not remember that these two papers have ever previously taken the same editorial position,” Jacobson wrote. “That this unprecedented step should have occurred underscores the wide support that there is in the community for your joining us and our eager anticipation for your visit.”

Enthusiasm was far from universal. The outgoing president of the Michigan Student Assembly had little use for a Ford visit. “It’s nice to know that the University is now going to serve as a burial ground for former unelected presidents, ” said Calvin Luker.

In the last week of January, the Board of Regents appointed Ford as an adjunct professor of political science – even though the president himself had not finalized a visit. A week later, Ford confirmed he would come to campus in the first week of April.

It represents the only time an American president – sitting or former – has taught at U-M.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Gerald R. Ford lectures to students in Rackham Auditorium. Behind him are, from left, Political Science Professors George Grassmuck and Albert Cover.Image: News and Information Services records, Bentley Historical LibraryChapter 4 A Vigorous Schedule

Awaiting Ford in Ann Arbor was a remarkably busy week for someone accustomed to a packed itinerary. “We have drafted what we consider a vigorous and demanding schedule,” Jacobson told Ford. “Perhaps we have included too much.”

Once Ford’s plane landed at Willow Run Airport on a Monday afternoon, he and his security detail rotated from classroom lectures and dinners to receptions, faculty luncheons and informal conversations with student groups. He gave lectures to 11 political science classes, from the freshman-level Introduction to American Politics to graduate courses in the American chief executive and legislative behavior.

“Such zealous performance of academic duty by an adjunct professor would overwhelm any inquiring auditor of public instruction, if one were involved, you may be sure,” Grassmuck said.

In addition to teaching classes, Ford met with honors students, researchers, teaching assistants, coaches, journalists, regents, high school principals, donors and football players.

“I have been told that thus far, not counting this class, I have had 10 other classes, three breakfasts, four luncheons, three dinners, four meetings, answered 372 questions and, according to student intelligence, used three different restroom facilities on campus,” Ford scribbled in his notes for his last course. All told, he interacted with some 1,500 students.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Professor George Grassmuck, a scholar of the executive branch, helped organize Ford's adjunct professorship.Image: News and Information Services records, Bentley Historical Library

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Students in the course, Introduction to American Politics, gathered in Rackham Auditorium for Ford's session.Image: News and Information Services records, Bentley Historical LibraryChapter 5 “Just Jerry Ford”

There was a strong emphasis on maintaining an academic atmosphere in the classes where Ford spoke. No visitors were allowed, enrolled students needed to produce a ticket, and only one session was open to reporters, who were told, “Questions of Mr. Ford will be permitted only by students in the course.”

Lecturing in Angell Hall, Rackham Auditorium and Lane Hall, Ford covered a wide swath of presidential life. He touched on the seizing of the American merchant ship Mayaguez, the Electoral College, his Whip Inflation Now (WIN) campaign, and the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty. Classes typically operated in a question-and-answer format, as did meetings with various student organizations throughout the week.

As president of the Political Science Graduate Students Association, Catherine Shaw had the honor of welcoming Ford and introducing him to her classmates for an hour-long discussion. In a way, the president was no stranger. A native of Grand Rapids, Shaw had grown up with Ford as her congressman; her parents and grandparents worked on the 1948 campaign that launched his political career.

“To me he was just Jerry Ford,” she recalled.

Still, the morning got off to a rocky start. Before Ford’s arrival at the Rackham Building, Secret Service agents removed one student from the meeting room. A previous indiscretion – unknown to those in the room – raised a red flag with agents, who made certain the student came nowhere near Ford.

When Ford did make his way to the building’s fourth floor and the grad students, Shaw was waiting for him. “I reached out to shake his hand,” she said, “and he stepped on my toe.”

Once Ford settled in with the students, he discussed the presidency, Congress, the Vietnam War and foreign policy, and his controversial pardoning of Nixon. “He was quite forthright about things,” Shaw said. “He was relaxed with us. I don’t know if we were relaxed with him.”

In addition to meeting the president, Shaw had an equally memorable moment from the visit. Once Ford was gone and students could unwind, she was approached by a classmate, Evans Young. “With all you’ve done today,” he told her, “the least I can do is take you to lunch.”

Lunch turned into a courtship that led to marriage in 1979. Shaw went on to become associate vice provost for academic and faculty affairs and Young was assistant dean for undergraduate education in the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Editors at The Michigan Daily greeted President Ford's return to campus.

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

President Ford had an open invitation to play golf at Radrick Farms.Image: Post-Presidential Office Files, Gerald R. Ford LibraryChapter 6 Rejections

For every class and group attended by Ford, there were others whose invitations were rejected.

“Our Department of Political Science has been besieged with participation requests. They have come from University faculty and students both within and outside Political Science, and from other groups off campus as well,” Grassmuck told Ford a month before his arrival. “And no doubt you and your staff have had related calls and invitations, too.”

A local realtor offered U-M officials use of a historic home for Ford’s stay. The 3,596-square-foot house, located along the Huron River, provided an in-ground pool, fireplaces, a working windmill and, most important, seclusion.

“This choice property, main structure and separate guest housing is perfectly suited for secured accommodation and privacy for President Ford,” wrote Thomas D. Gooding.

(Ford spent his nights on campus in an upstairs bedroom of the President’s House, hosted by Robben Fleming and his wife, Sally.)

A graduate student in linguistics hoped to meet Ford to analyze the former president’s tone of voice. “There is a radical difference in the political voices exemplified by Mr. Nixon, Mr. Ford and Mr. Carter,” wrote William W. Crawford. “While Mr. Nixon’s speaking style indicated a certain ‘distance’ from the audience, both Mr. Ford and Mr. Carter showed varying degrees of ‘intamacy’ (sic) with the audience.”

And officials at Radrick Farms Golf Course, one of U-M’s two courses, offered Ford an honorary membership and an open invitation to play a round while in town. “Everyone is familiar with your interest in golf,” they wrote. Alas, there was no time.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Coach Bo Schembechler joined Ford in meeting with reporters during spring practice at Ferry Field.Image: News and Information Services records, Bentley Historical LibraryChapter 8 Bo and Benny

While Ford turned down an opportunity to golf, he did find time for football. It was a cold, blustery afternoon when he visited Ferry Field and the football team for spring practice. Forty miles to the east, the Detroit Tigers were opening their 1977 home season, while the Wolverines were working out in preparation for the fall.

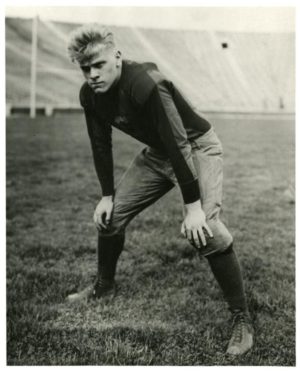

The team was coming off a remarkable season, with a 10-2 record and a No. 3 national ranking. Ford knew a few things about winning. As a sophomore and junior, he played on undefeated teams that won the national championship. At 6 feet and 190 pounds, he played center for the Wolverines; Michigan Stadium was less than a decade old and the winged helmet had yet to debut.

Ford’s senior year was a setback, with the team finishing 1-7 and failing to register a Big Ten win. Ford, however, was named MVP and invited to play in the East-West Shrine Game, a college all-star game.

That spring afternoon in 1977, Ford and Coach Bo Schembechler stood in the end zone and watched the players run their drills. Joining them were men’s basketball coach Johnny Orr and two of Ford’s old coaches, Benny Oosterbaan and Cliff Keen. It’s possible Ford kept an eye on freshman linebacker Jeff Bednarek, wearing the same No. 48 as he did 40 years earlier. Ford’s jersey was officially retired in 1994.

Ford would later say his U-M playing days prepared him for the criticism that comes with elected office. Disparaging remarks “helped me to develop a thick hide,” he wrote in his memoir, “and in later years whenever critics assailed me, I just let their jibes roll off my back.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Ford in his senior year with the U-M football team.

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Ford and his security detail leave the Michigan Union for a class at Angell Hall.Image: News and Information Services records, Bentley Historical LibraryChapter 9 “A Marvelous Experience”

Some criticism came with Ford’s visit – the students’ questions were too soft, the professorship was a publicity stunt, the lectures were underwhelming – but the overall assessment was positive. Students said they appreciated Ford’s honesty and relaxed nature, as well as the opportunity to interact with a former president.

“What did he accomplish? Well, not all that much,” wrote the editors of The Michigan Daily. “It was fun to have him here, and his visit no doubt showed some students that a President is neither an ogre nor a titan, but a person who breathes and blows his nose like the rest of us.” Still, the editors praised “his ability to speak intelligently on national affairs.”

After a week of 12-hour days, Ford was said to appear “drawn and fatigued.” Still, he told student reporters the week had been “most enjoyable.”

Organizers in the Political Science Department were thrilled about the visit, and told Ford as much.

“It was a marvelous experience for all of us,” said Jacobson, the department chair. “You gave some 1,500 students and more than 100 faculty with whom you had close contact an unparalleled opportunity to understand more fully the United States system of government and the problems that we as a country face in this era of technological complexity and global interdependence.

“Your courtesy and graciousness in responding to our sometimes-repetitive questions won universal admiration. The calm way in which you handled even provocative questions was a good lesson for all of us. You made us aware of the multiplicity of values involved in decisions about national policy, the uncertainty about the consequences of action, and the consequent inevitability of debate.

“You showed us that even serious disagreements can be discussed rationally and with civility.”

That same day, the LSA Executive Committee “enthusiastically” endorsed a request from Jacobson to ask Ford to return to campus in the fall. It was an invitation the president accepted, and Professor Ford would teach again in November.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Ford during a class with undergraduates in 1977.Image: News and Information Services records, Bentley Historical LibraryChapter 10 Legacy

Gerald Ford last visited U-M in 2004, nearly 70 years after his graduation. He and Betty Ford attended the groundbreaking for a new building to house the Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy – successor to the Institute of Public Policy Studies, one of the organizers of his visiting professorships.

Ford died in 2006 at age 93. After a national funeral in Washington, his body was flown to Michigan for burial. As Air Force One made its way to Grand Rapids, it dropped down over Ann Arbor and passed slowly over the campus for a final farewell.

Ali Kahil, a participant in the Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program, provided research assistance for this story.

Sources: Department of Political Science papers, Bentley Historical Library; Post-Presidential Office Files, Gerald R. Ford Library; News and Information Services records, Bentley Historical Library; George Grassmuck papers, Bentley Historical Library; A Time to Heal: The Autobiography of Gerald R. Ford, by Gerald R. Ford; contemporary newspapers accounts.