Lost Star

By James Tobin

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

"I can’t banish the feeling that there is a serious deficiency of academic freedom..."– Lawrence Klein

-

Chapter 1 The Fourth Man

In the days of Senator Joseph McCarthy, when Americans feared a Communist conspiracy to subvert the West, three junior members of Michigan’s faculty were tarred by the brush of suspicion.

Investigations ensued — one by the House Un-American Activities Committee, two by committees of the faculty. For months these events made headlines. In the end, President Harlan Hatcher fired two of the men and censured the third.

For many years, the controversy was all but forgotten. But in the 1980s, as academe reconsidered its record in the McCarthy years, a campaign arose among the faculty to extend a gesture of reconciliation to the three scholars, all still living. When the regents declined to approve the idea, faculty acted on their own. In 1991, they established an annual lecture on academic freedom to honor the three — Chandler Davis, Clement Markert and Mark Nickerson.

But there was another thread to this story, one far less well known than the public ordeals of the three men who, for a time, magnetized the attention of the campus.

Behind closed doors, a fourth member of the faculty went through a parallel ordeal. He escaped the spotlight of scandal that fell on Davis, Markert and Nickerson. But he was also denied a public acknowledgement that the University might have done him a grave wrong.

And this was not just any young scholar. This was Lawrence Robert Klein. In 1980, as a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, he won the Nobel Prize in economics.

When Klein died in 2013 at 93, he was memorialized as one of the great economists of the 20th century.

But no one wrote about the ugly and secret fight that had pushed him away from Michigan so long ago.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Harlan Hatcher, a scholar of English literature, accepts Regent Roscoe Bonisteel’s congratulations at his inauguration as U-M’s eighth president in 1951.

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

During World War II, Lawrence Klein became one of the first social scientists to blend economic theory with statistical modeling. The result was a reliable method for predicting economic change on a national scale.Chapter 2 Early Brilliance

Born in 1920, Lawrence Klein grew up the second of three children in Omaha, Nebraska. His father was an office clerk. He dreamed of a career in baseball, but at the age of 10 he was disabled when struck by a car. During World War II, his childhood injury kept him out of the service. He spent the war years mostly in school, first at Los Angeles City College; then at the University of California, Berkeley; then at M.I.T., where he earned one of that school’s first doctoral degrees in economics in 1944.

His early brilliance earned him a job straight out of grad school at the prestigious Cowles Commission at the University of Chicago. There, a few pioneering scholars were infusing traditional economic theorizing with statistics. This was a new specialty called econometrics.

The Chicago group was trying to predict what would happen to the U.S. economy when the war ended. Many Americans, including most economists, feared another depression.

Klein was fascinated by the use of statistical modeling to predict the economic future. Like a meteorologist using radar to study the weather, he fed streams of data into his models.

Results in hand, he said no, the United States wasn’t heading for another depression. In fact, there was going to be a boom after the war.

The war ended. Servicemen flooded home. The economy shifted from war to peace, and soon the U.S. was heading into a great economic expansion.

The doomsayers had been wrong and Klein had been right.

Not yet 30 years old, he was one of the most promising young economists in the world.

The doomsayers had been wrong and Klein had been right.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

I. Leo Sharfman, chair of Economics from 1927 to 1955, was one of the first Jews to lead a department at U-M — a fact that rankled one of his colleagues.Image: Available online at Faculty History Project.Chapter 3 A Promise of Promotion

In quick succession Klein designed economic models for the government of Canada; studied with major economists in Europe; and worked in Washington under Arthur Burns, future chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve.

In 1949, he was snapped up by Michigan as a research fellow in the Survey Research Center. In 1950, he accepted a joint appointment as lecturer in the Department of Economics, where he was promised swift promotion.

His output was prodigious. He wrote a definitive study of Keynesian economics; a history of economic fluctuations between the world wars; and the leading textbook on econometrics. With his students in a graduate seminar, Klein designed a statistical model of the U.S. economy that became a standard tool in the field.

Members of Economics Department knew they had an academic superstar on their hands. Early in 1953, Professor Leo Sharfman, the long-time chair, told Klein that in one more year, the Department would leapfrog him from lecturer to full professor with tenure, a rare and prestigious sign of confidence.

Then U-M’S leaders were told by investigators from the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) that Klein’s name was on a list of some 15 professors and students suspected of being secret members of the Communist Party.

Klein’s name was on a list of some 15 professors and students suspected of being secret members of the Communist Party.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The text of President Hatcher’s January 1953 telegram to U.S. Rep. Harold Velde, chair of HUAC, assuring Velde of U-M’s “cooperation to the fullest extent” with HUAC’s investigation of Communists in higher education.Image: Marvin Niehuss papers, Bentley Historical Library.Chapter 4 “Un-American Activities”

A decade earlier, in his early 20s, Klein had been attracted to left-wing politics. This was hardly unusual among idealistic intellectuals of the 1930s and early ‘40s, many of whom were troubled by the shortcomings of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and appalled by the rise of Nazi Germany.

But in 1944 or ’45, Klein went farther than most by doing work for the Communist Party. In practical terms this meant, by his own account, that he went to some Party meetings and taught some adult classes on Keynesian economics offered at Party-run schools in Boston and Chicago.

He dropped the connection after he married in 1947 and began to raise a family. He remained a leftist. He defined himself as a democratic socialist in favor of national economic planning on the Scandinavian model. But his time and attention were now consumed by his work in economic forecasting.

* * *

Joe McCarthy was only the most famous of the politicians who cast themselves as red hunters. His special targets were the State Department and the U.S. Army. Others scrutinized Hollywood, the theater, the labor movement, the civil rights movement — any institution that might be purveying Communist propaganda.

U.S. Rep. Harold Velde, an Illinois Republican and former FBI agent who became chair of the House Un-American Activities Committee after the off-year elections of 1952, took aim at the nation’s schools and colleges. He deputized U.S. Rep. Kit Clardy, a Lansing Republican just elected to the House, to find Communists on Michigan’s campuses.

In January 1953, Detroit newspapers reported that HUAC had compiled a list of some 15 Communists, past or present, on U-M’s faculty. President Hatcher immediately cabled Velde: “We wish to inform you of our willingness to cooperate with you to the fullest extent,” and he directed any faculty member who received a HUAC subpoena to do the same.

Hatcher sent his chief lieutenant, Marvin Niehuss, a law professor and vice president for academic affairs, to find out who was on HUAC’s list. Niehuss got HUAC to cut the names to a handful — a couple of graduate students and five faculty members, including Chandler Davis, Clement Markert, Mark Nickerson and Lawrence Klein.

We wish to inform you of our willingness to cooperate with you to the fullest extent.

– Harlan Hatcher to the House Un-American Activities Committee -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Mark Nickerson, pharmacologist; Chandler Davis, mathematician; Clement Markert, biologist — the three faculty members who became the public focus of HUAC’s investigation at U-M.Image: The Michigan Daily.Chapter 5 The Three

Klein did exactly what the University asked of him. With the HUAC hearing looming, he went to his chair, Professor Sharfman, and Vice President Niehuss. He told them frankly about his earlier association with the Communist Party — why he had joined and why he had quit.

Next he met with HUAC investigators and did the same. HUAC gave him a clean bill of health and said he would not be called to testify in public. A few friends and colleagues knew what had happened, but Klein’s name never surfaced in press reports.

Congressional red-hunters normally demanded a price for the absolution that HUAC had given Klein — the person under suspicion must “name names.” That is, he must inform on other Communists to prove he had renounced the Party. Whether Klein did so in his private meetings with HUAC is not known.

He quietly went on with his work.

Then, in public hearings in Lansing in June 1954, Davis, Markert and Nickerson refused to answer HUAC’s questions about any ties with Communism. (Another professor, who was gravely ill, was excused from testifying.)

Davis invoked his First Amendment right to political freedom and the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination. Markert and Nickerson invoked only the Fifth Amendment.

President Hatcher promptly suspended the three men and directed the faculty to investigate. Their jobs, not to mention their reputations, hung in the balance.

* * *

The three men met separate fates.

Chandler Davis told faculty committees that his politics were none of their business. Hatcher then fired him. After years in court, he served several months in prison for contempt of Congress.

Clement Markert and Mark Nickerson acknowledged that their faculty colleagues, unlike members of Congress, had a right to ask where they stood on Communism. Each spoke frankly with the committees about past Communist ties and said they were no longer members.

Markert’s penalty was only to be censured by the administration for refusing to cooperate with HUAC. Strong support from colleagues apparently helped save his job. But he soon left Michigan for a position at Johns Hopkins. He wound up as chair of biology at Yale.

Nickerson appeared to be in the same position as Markert. He had told all to the faculty committees, and he was regarded as one of the most important pharmacologists of his generation. But he was a difficult man, and he had bitter enemies in the Medical School. When his superiors said they could no longer tolerate him, Hatcher fired him, too.

With the matter resolved, Hatcher gave a long summing-up to the faculty.

Any professor, he said, “owes his colleagues in the University complete candor and perfect integrity, precluding any kind of clandestine or conspiratorial activities. He owes equal candor to the public. If he is called upon to answer for his convictions it is his duty as a citizen to speak out. It is even more definitely his duty as a professor.

“Of one thing I am sure. Nobody’s freedom has been invaded or abridged at the University of Michigan, and the proper way to keep it sturdy and productive is to exercise it responsibly in keeping with our high and honorable tradition.”

The scandal over reds at Michigan appeared to be over. But the matter of Lawrence Klein had only begun.

“Of one thing I am sure. Nobody’s freedom has been invaded or abridged at the University of Michigan."

– Harlan Hatcher -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

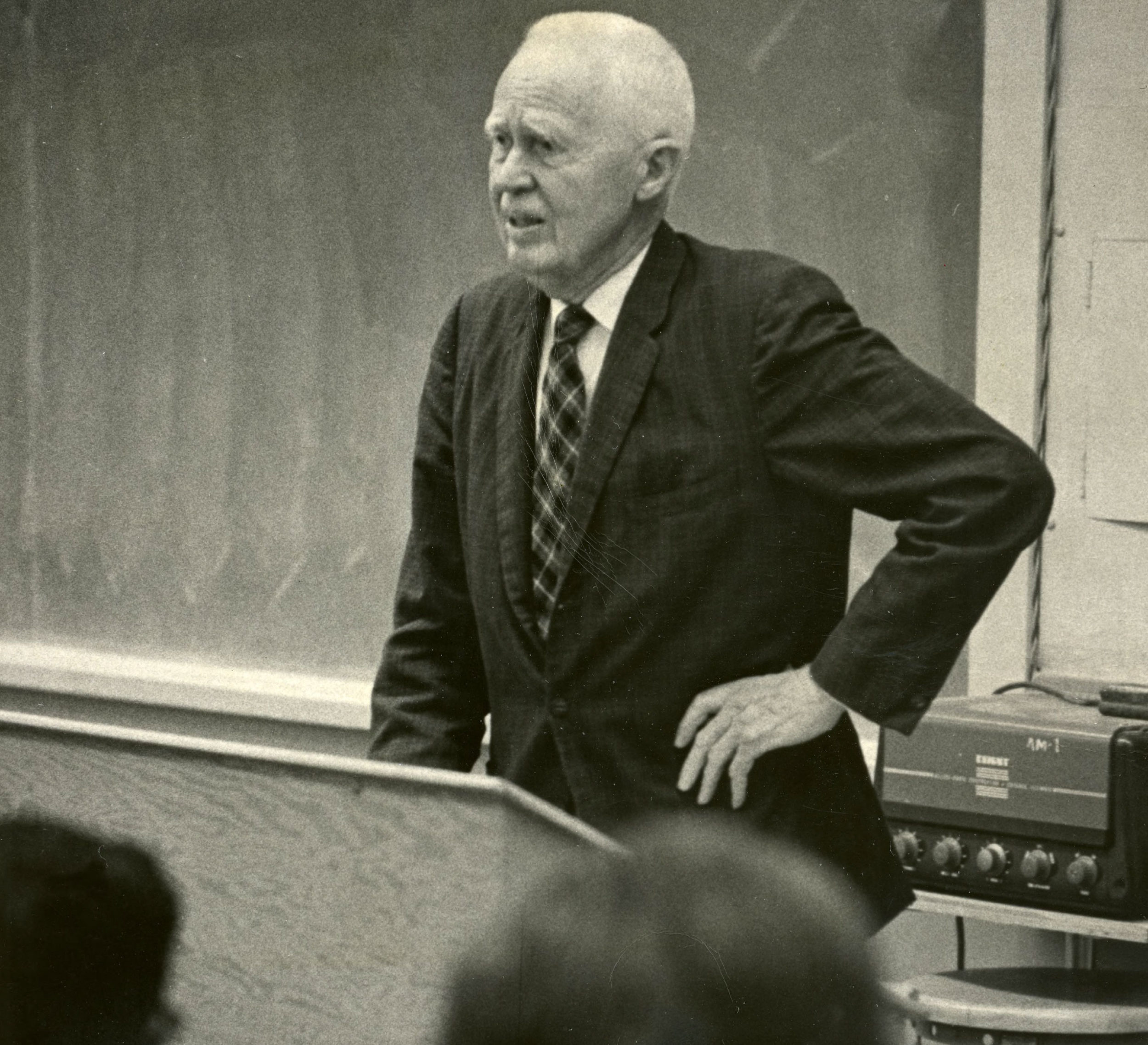

Gardner Ackley, a prominent Keynesian economist, took up the cause of Klein’s promotion when he succeeded Leo Sharfman as chair of the Department of Economics.Image: Available online.Chapter 6 The Case for Klein

The laborious process of promoting Klein to a full professorship in Economics had been put off at least once already. Professor Sharfman, the chair, was buying time until the HUAC storm had passed, though he had “to suppress a modest staff rebellion” by those who wanted Klein to be promoted with no further delay, according to one professor.

Now Klein himself asked for a postponement. In the fall of 1954, as the faculty conducted its hearings with Davis, Markert and Nickerson, he took a leave without pay and went off to England, where he worked as senior researcher at Oxford University’s Institute of Statistics.

In Ann Arbor, Sharfman was just stepping down as chair of Economics. He was replaced by Gardner Ackley, a macroeconomist who was a star in his own right. Ackley wasted no time in proposing that Klein be lured back to Ann Arbor with a promotion from lecturer to full professor with tenure.

To win that promotion — nearly unheard of without intermediate promotions to assistant and associate professor — Klein would have to pass muster at four levels in ascending order: the Department of Economics; the College of Literature, Science and the Arts (LSA); the vice president for academic affairs and the president; and finally, the University regents. To propel Klein’s name up and over these obstacles, Chairman Ackley prepared an exhaustive dossier.

When U-M had first hired Klein in 1949, Ackley told LSA’s leaders, rumors had reached Ann Arbor that he was an enfant terrible, a “genius intolerant of mere mortals.” But “either this report was untrue,” Ackley said, “or something had happened to him before he arrived; for we have observed a modest, cooperative, and tactful individual…always friendly [and] conscientious in performance of his responsibilities.”

Ackley and his colleagues — most of them — were satisfied that any questions about Klein’s judgment or character could now be safely forgotten.

“We have observed him closely for four years…. He is as objective, experimental, and open-minded as any among us…” and he had shown “no evidence of any Marxist dogma, no indication of rigid positions, no blindness to facts or arguments on any side.”

As for his stature in economics, there was no controversy at all.

Very few scholars, even after decades of work, ever win the kind of endorsements that now came in for Klein. His promotion had the backing of no fewer than six future winners of the Nobel Prize in economics, not to mention Arthur Burns, then chair of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Council of Economic Advisors.

Summing up his case, Ackley said: “We have no fear of his views. Nor need any member of the University community. There is every reason to suppose that Klein’s scholarship and teaching will continue to add luster to the reputation of the Department and the University.”

* * *

Eighteen senior members of the Economics faculty endorsed Ackley’s plea for Klein’s promotion to full professor. Two dissented. Both held joint positions in the School of Business Administration, which had a rocky history with the Economics Department.

One was Robert Spivey Ford, an associate dean.

The other was William Paton, the star of U-M’s business school, a professor at Michigan since World War I, widely regarded as one of the founders of modern business accounting, and a man so conservative he thought Social Security “was a curse on our society,” as an admirer once put it.

We have no fear of his views. Nor need any member of the University community.

– Gardner Ackley -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

After speedy progress to a Ph.D. at Michigan, William Paton was named to the Economics faculty in 1916. He soon was recognized as a pioneer in business accounting methods. When the School of Business Administration was founded in the 1920s, he split his appointment between LSA and Business.Chapter 7 Professor Paton

Born in 1889 and raised in Michigan’s Copper Country, William Paton was the son of a small-town school superintendent. His mother oversaw Calumet’s rotating collection of 50 books lent by the state library for six months at a time, and her son always read all 50.

With money he earned from odd jobs, he raced to three degrees at Michigan — B.A. in 1915 (after which he started teaching economics), M.A. in 1916, Ph.D. in 1917. His dissertation was published as Accounting Theory with Special Reference to the Corporate Enterprise, a foundational document in the new field of public accounting.

By 1921 he was a full professor with appointments in Economics and the new School of Business Administration. Even in his 30s, he was the certainly the Business School’s best-known figure and arguably its most brilliant.

During the Depression he helped to restore faith in accounting with key innovations in standards and practices. He authored leading textbooks; won all the major awards in his field; and earned one of Michigan’s first named professorships.

In the classroom he was a powerful and exacting presence. One student recalled “his incisive mind, his impatience with sloppy reasoning, his endless stock of homely anecdotes and Biblical references, his interest in his students’ careers, and his amazing ability to remember names and faces.” He was charming, earthy, charismatic, funny, stubborn and intolerant of mediocrity.

In national politics, he revered free enterprise, hated Franklin Roosevelt and assaulted the safety-net thinking of New Deal economists.

In campus politics, he was a gadfly from the right who often fought with liberal colleagues in the Economics Department. Even admirers said Paton was “a poor compromiser” seldom troubled by self-doubt. He once published an article on the virtues of living in underground dwellings. “If this aberrant idea be taken by some of his critics as proof that his notions of economics and politics are those of a caveman,” one of his students wrote, “he would be totally unconcerned.”

When Gardner Ackley took up the cause of Lawrence Klein’s promotion in the fall of 1954, Paton declared war.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The University’s old Economics Building in the early 1950s, scene of the Department’s running battle over the fate of Lawrence Klein.Chapter 8 A Department at War

In the fall of 1954, Klein’s supporters and foes argued about his promotion in two long, contentious meetings.

Paton believed Klein’s “conversion” was “only skin-deep” and that he was “aggressively socialist in his entire outlook.” Besides, Paton said, there were already enough leftists in the Department.

Ackley retorted that Klein now believed in nothing more radical than the sort of welfare state favored by left-leaning New Dealers and the democratic socialists of Scandinavia. “Obviously,” he said, “such views can be compatible with (1) complete loyalty to the American way of life, and (2) scientific objectivity in his professional work. … We are convinced that Klein feels no mission to convert anyone to his own social and political views.”

As for the admixture of “left” and “right” in the Department, Ackley said: “Professor Paton stands at the edge of such a spectrum. For him, such institutions as Social Security are not only ‘humbug’ but dangerous to the social fabric. I am glad that we have such views represented. They may even be the ‘truth.’ I am only unhappy that Professor Paton sometimes finds it necessary to lump together all views not his own as ‘leftist,’ which also can mean ‘pink,’ or ‘Socialist,’ or worse.”

Colleagues detected a subtext in Paton’s remarks.

As William Haber, a senior member of the Department and later dean of LSA, would recall it, they had “an anti-Semitic overtone. He [Paton] referred to the voice of Larry Klein, that it had…a sound that’s associated with Jewish speakers or Jewish people. And he didn’t spell it out; he didn’t have to. It was too crystal-clear to me, and it was clear to others who were less sensitive about it.”

Haber made a retort that sent Paton storming out of one meeting. He was brought back, but he said the Department might as well pay dues to the Communist Party if members insisted on promoting Klein — and if they did, he would personally lobby members of the board of regents to block the appointment.

The Department voted 18-2 for the promotion.

Next, Paton went in search of more ammunition. Acting on his own, he solicited opinions of Klein from 10 more economists. None were experts in Klein’s field of econometrics.

Three returned letters highly unfavorable toward Klein, while three were only mildly unfavorable. The rest were favorable, and even Paton concluded that one of the “highly unfavorables” should be discounted.

“This is not a very good percentage,” Ackley remarked in a letter.

The 18-2 majority in Klein’s favor was good enough for Ackley, who forwarded the recommendation to LSA Dean Charles Odegaard. Ackley proposed that Klein’s appointment should consist of a three-quarter-time post in the Economics Department and a one-quarter commitment to the Survey Research Center — with tenure, meaning lifetime job security.

Members of the Economics Department waited in suspense.

So did Klein.

Across the Atlantic, officials at Oxford University offered him a permanent position with tenure. Klein put them off, waiting for word of a competing offer from Michigan.

[Paton] referred to the voice of Larry Klein, that it had…a sound that’s associated with Jewish speakers...

– William Haber -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Paton spiced his Business School lectures on accounting with homey stories of his early life in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and excoriations of liberal politicians.Chapter 9 Two Compromises

Twice, LSA Dean Odegaard and the College Executive Committee came back to Gardner Ackley to ask for more information about Klein’s fitness. Both times, Ackley patiently stuck to his guns. “Klein,” he repeated, “is a scholar of remarkable technical competence, achievement and promise.”

Finally, the dean endorsed Ackley’s recommendation — promotion to full professor with tenure — and passed it up to Vice-President Niehuss. The decision now lay with him and President Hatcher. They held an informal discussion about the matter with members of the board of regents.

On June 8, 1955, Niehuss sent the administration’s decision back to Dean Odegaard. It was a compromise. The president would recommend to the regents that Klein be appointed full professor, but without tenure. At a later date, he could be considered for tenure again.

* * *

Now the decision fell to Klein — whether to choose Michigan or Oxford. Ackley cabled the young economist to urge him to accept U-M’s offer, then followed up with an impassioned letter.

Klein replied by telegram: “Badly want tenure.” Ackley tried again, but on the matter of tenure the administration would not budge.

When he had left Ann Arbor the previous year, Klein promised himself he would return to the United States only to accept a tenured position. Now, “in recognition of the sincere efforts made on my behalf by friends and colleagues” at U-M, he decided on a compromise of his own. He would accept Michigan’s offer, despite the lack of tenure.

That seemed to be the end of it.

But the battle between Ackley and Paton was not over, and in the fall of 1955 it speedily came to a climax.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Marvin Niehuss, vice president for academic affairs and dean of the faculties, was President Hatcher’s point man in the HUAC investigation.Chapter 10 Paton’s Finale

Professor Paton now interceded again. First he followed through on his threat to lobby regents not to confirm Klein’s promotion.

His letter to them has not survived, but he likely repeated what he wrote to Vice-President Niehuss: “This appointment has no justification. [Klein] was a postwar member of the Communist Party, and remains a ‘dedicated’ supporter of the Norwegian type of socialism, generally conceded to be the nearest thing to the totalitarian brand to be found outside the Iron Curtain. Some of us here regard him as an arrogant and generally disagreeable person…”

Next, Klein received an anonymous letter in England. As he recalled years later, it was “a very nasty letter… telling me not to come [to U-M] and all the dire things that would happen if I did come.” Authorship of the letter was never verified, but members of the Department told Klein later that Paton had written it.

In some distress, Klein wrote Ackley: “A few weeks ago, I received an anonymous letter outlining Paton’s recent moves against my appointment. I am not certain whether the tip was sent as a warning by a friend of what to expect on my return or as a threat by a foe against my returning at all.

“Should I take seriously Paton’s activities? He now approaches the regents and administration directly to let my appointment expire at the end of the current year and makes the veiled threat of carrying the case to the public if he gets no satisfaction from University authorities.

“I had planned to come back full of enthusiasm for various research and teaching projects, but I don’t look forward to the bother of carrying on this fight over again.”

A deeply bitter exchange of letters between Ackley and Paton followed.

Ackley wrote, in part: “I will not dwell on the fact that your new actions have again cruelly exposed a man and his family — who had already suffered a great deal — to renewed uncertainty, insecurity, and doubt. … I can imagine circumstances in which any of us might feel compelled to dissent from the actions and judgments of all of our colleagues, just as you have done. But I cannot imagine doing it behind their backs. … We had to learn of your actions through a rumor which reached us from England.

“Please do not pretend that this was a mere oversight… Your action…appears to me to have deliberately flouted the rules of behavior which are necessary for any kind of responsible group life and action.”

Paton replied: “This is wild and grossly insulting talk and I deny your accusations and insinuations point blank… [Y]our effort to castigate me and put me in a bad light with my departmental colleagues and with College and University officials is an almost incredible performance, without justification…”

But whether Paton had written the anonymous letter or not, he had already won his war.

* * *

Klein wrote to Vice-President Niehuss to ask for his frank assessment of his future at Michigan.

Niehuss’s reply was guarded, even tepid. At the end of the academic year, he said, he would recommend that Klein’s appointment — still without tenure — be extended for another year, but “I cannot predict the action of the Board of Regents on this recommendation.”

That sealed Klein’s decision.

In a handwritten note back to Niehuss shortly before Christmas 1955, Klein resigned his posts at Michigan and said he had accepted Oxford’s “magnificent offer, with long tenure…This and other British universities have given me such a strong sense of freedom of thought that I feel I cannot refuse this offer at Oxford.”

When Gardner Ackley begged Klein to change his mind, Klein replied: “Your letter is very kind and certainly makes me hesitate, yet I can’t banish the feeling from my mind that there is a serious deficiency of academic freedom in the summation made by Niehuss. It isn’t the risk or uncertainty of the situation that bothers me so much… And it isn’t any fear of Paton’s actions. It is simply a feeling that it is wrong for the regents to pay heed to Paton. I don’t put much value in tenure as such; I simply don’t like the reasons for which it is withheld…

“I shall miss Ann Arbor a lot… I am sorry to have proved to be such a nuisance and only hope that the fight for some basic principles was justified because of the nature of the issues at stake.”

This is wild and grossly insulting talk...

– William Paton to Gardner Ackley -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

A street scene at England’s Oxford University in the 1950s, when Lawrence Klein taught there.Image: Allan Cash Picture Library.Chapter 11 Conspiracy Theory

Many years later, in 1979, Gardner Ackley was interviewed for a history of the Department of Economics. The interviewer was Marjorie Cahn Brazer, wife of the economist Harvey Brazer, who joined the Department in 1957.

Brazer already had interviewed William Paton, including questions about the Klein affair. In her conversation with Ackley, she said: “[Paton’s] position is that it was not because [Klein] was a former Communist that he objected to the appointment, but rather the elevation to a high professorial rank with tenure of someone who had been only a lecturer…”

“Well, that may be what he says,” Ackley replied. “I don’t believe it.

“There were two reasons he opposed it. One was the former Communism. The other was — I’m sorry to have to say this but I think it might as well get into this record…— was pure anti-Semitism…

“One day…[Paton] came over to explain to me that this was all a plot by Sharfman and Haber and [Richard] Musgrave and [Wolfgang] Stolper…all the Jews he could think of in the Department…to solidify the Jewish control of the Department. And I ought to understand that and to recognize it for what it was, and that the Klein appointment was just part of that.”

Ackley said he had all but thrown Paton out of his office and never spoken to him again.

[Paton] came over to explain to me that this was all a plot …to solidify the Jewish control of the Department.

– Gardner Ackley -

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

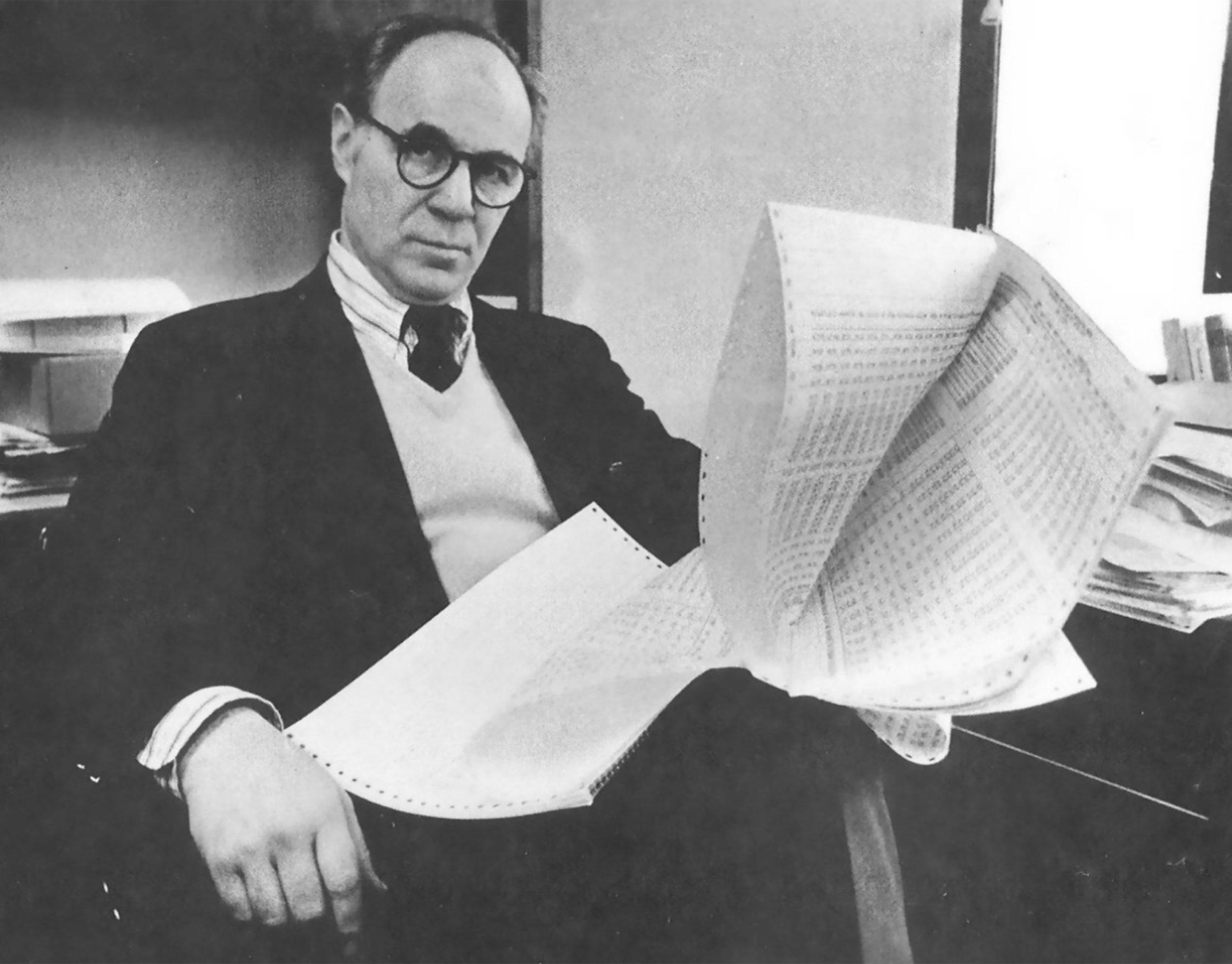

Klein at the University of Pennsylvania, where he held a tenured chair in economics from 1958 until his retirement in 1991.Chapter 12 Epilogue

Gardner Ackley spent several years as chair of the Economics Department, then joined President John F. Kennedy’s Council of Economic Advisers. He served as chair of the council under President Lyndon Johnson from 1964 to 1968. He spent another year as U.S. ambassador to Italy before returning to the U-M faculty. He retired in 1984 and died in 1998.

* * *

After the Klein affair, William Paton had nothing more to do with the Department of Economics. He retired from the faculty in 1959 after more than 40 years of teaching and research. He remained active in academic accounting circles for many years, corresponding with hundreds of former students.

In 1976, the Business School named its new accounting building for him, acknowledging him as both a superb teacher and a founding member of his profession. He died in 1991 at the age of 101.

In 2004, over the objections of some alumni and Paton’s descendents, the Paton Building was torn down to make way for the new Ross School of Business building. But to continue the recognition, the Ross School’s new Center for Research in Accounting was named for Paton.

* * *

In the late 1980s, Marvin Niehuss, long retired, was interviewed by a student, Adam Kulakow, who made a documentary about the Red Scare at Michigan. Kulakow asked if Lawrence Klein had been forced out of Michigan on political grounds.

“I don’t know,” Niehuss replied. “I’m afraid so.” Then he qualified his answer, saying Klein had chosen to leave “on grounds that he had been mistreated here. I don’t think he did it on grounds that we didn’t accept his politics. I don’t think the department [of Economics] was a happy place for him to be. Of course he made a great name for himself, and he was making it here, if we could have kept him.”

William Paton had once been Niehuss’s teacher in the Business School. Later the two became faculty colleagues and friends.

“He was one of our great teachers and a great person,” Niehuss said, “but he was very inflexible on things of this sort… He was a strong-minded conservative who said what he thought, and what he said about [Klein] was not correct.”

* * *

Harlan Hatcher also was interviewed by Adam Kulakow. He wasn’t asked about Klein, specifically, but his responses about Davis, Markert and Nickerson reveal much about his view of the entire episode.

“It’s very difficult — I must emphasize that — to recreate the tensions which were produced in the society as a result of the confrontations with Russia following the war,” he said. “Here you have a unique situation, in a period of cold war and of deep tensions, a period critical to the University’s welfare — we were starved for money. … How were you going to build this institution unless you have the support and the confidence [of the public]?

“The McCarthy hysteria and the extremes to which they were going had become entirely apparent. They were very destructive, and the question was how to preserve the integrity of our institutions in the face of that threat….

“The president…has got to be terribly aware at all points of a hundred different points of concern that affect the welfare of the institution…

“You have a vision for the institution. You want it to serve. You want it to be preserved. It’s a precious thing that you’ve created. You can’t destroy it, and you can’t allow it to be destroyed. You build it up over a hundred years; you’re not going to kill it by some wayward act…

“The issue is the rights of the individual versus the good of the institution…

“I must say it was a most painful and difficult period.”

* * *

Lawrence Klein’s brush with McCarthyism made no headlines in Michigan, nor did it taint the rest of his career. After several more years at Oxford University, he moved back to the United States in 1958 to accept a full professorship with tenure at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. By common consensus, his life’s work established a new paradigm in economics. He did more than anyone else to show how a statistical model could represent a nation’s entire economy, and to use that model to predict the future.

In 1976, he was Gov. Jimmy Carter’s chief economic adviser during Carter’s successful run for the presidency. But he turned down Carter’s invitation to chair the Council of Economic Advisers. He returned to his work at Penn.

In 1977, U-M awarded Klein an honorary degree, though with no public acknowledgement of how he had left the faculty in the 1950s.

Harold Shapiro, later president of U-M, then of Princeton University, was chair of the Department of Economics when the degree was awarded. The honor to Klein, he recalled recently, “to my knowledge was never thought of as a token for anything but his outstanding work… Nevertheless in the back of my mind I felt some satisfaction that here was one more piece of evidence that the University had put the earlier set of issues behind them.”

In 1980, Klein was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics. The Nobel committee said: “Few, if any, research workers in the empirical field of economic science have had so many successors and such a large impact.”

He retired in 1991 and died in 2013.

* * *

Ellen Schrecker, the Princeton historian whose 1986 book, No Ivory Tower: McCarthyism and the Universities, remains the definitive treatment of the subject, said Klein’s departure from Michigan, unheralded as it may be, was “perhaps the most egregiously political denial of tenure” that occurred in the 1950s on any American campus.

Sources: Documents that reveal many details of Lawrence Klein’s departure from U-M, as well as the Davis-Markert-Nickerson controversy, are held chiefly in the papers of Marvin Niehuss, Harlan Hatcher, the University Senate, the U-M chapter of the American Association of University Professors and the Department of Economics, all at the Bentley Historical Library. The Department’s papers include transcripts of Marjorie Cahn Brazer’s interviews with members of the Department and her unpublished history, which deals with the Klein case. Praise for William Paton appears in Herbert F. Taggart, et al, “A Tribute to William A. Paton,” Accounting Review (January 1992). Key secondary sources are David A. Hollinger, “Academic Culture at the University of Michigan, 1938-1988,” in Science, Jews and Secular Culture (1998) and “2009 Postscript and Second Thoughts”; Ellen Schrecker, No Ivory Tower: McCarthyism and the Universities (1986); and Peggie J. Hollingsworth, ed., Unfettered Expression: Freedom in American Intellectual Life (2000). Also revealing are interviews conducted with many of the surviving principals in the Davis-Markert-Nickerson episode by Adam Kulakow for the documentary he created as a student in the late 1980s, “Keeping in Mind: The McCarthy Era at the University of Michigan.” Videotapes of the interviews, as well as the documentary itself, are held in Kulakow’s collection at the Bentley Historical Library.

I must say it was a most painful and difficult period.

– Harlan Hatcher