Such Horrible Business

By James Tobin

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Anatomy… familiarizes the heart to a kind of necessary inhumanity.– William Hunter, Scottish anatomist

-

Chapter 1 “A Necessary Inhumanity”

Early one morning just before Christmas 1857, a ghastly discovery was made in the hamlet of Cambridge Junction, some 40 miles southwest of Ann Arbor. Men arriving for work on the construction of a church found an unholy mess—smears of blood, tufts of hair, signs of heavy objects being dragged across the floor. In the little graveyard in back, they found heaps of fresh earth next to empty graves.

The local sheriff knew just where to look for the missing bodies—the medical department at the University of Michigan. Sure enough, there they were, being hidden by medical students. The students handed the bodies over and went back to their studies, embarrassed but unperturbed. After all, they hadn’t dug up any bodies. The medical department was simply the terminus of an illicit supply chain as indispensable to medicine as surgical stitches and scalpels.

Incidents like this happened again and again in the 1800s, not just at Michigan but wherever professors taught medical students how to save lives.

For many years, the best physicians had considered it a settled fact that no one could legitimately practice medicine without a thorough, detailed study of the human body. Another settled fact: No one could master anatomy by studying a book, even a text illustrated in the fine-grained detail of Gray’s Anatomy, first published in 1858. The medical student had to study the anatomy itself—the flesh and organs and bones of real human beings. No one found dissection pleasant. But as the Scottish anatomist William Hunter had put it: “Anatomy is the basis of surgery. It informs the head, guides the hand, and familiarizes the heart to a kind of necessary inhumanity.”

Science requires specimens. But centuries of belief about the nature of the human body stood in science’s way.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Rural graveyard.Image: Library of Congress

Science requires specimens. But centuries of belief about the nature of the human body stood in science’s way.

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

A 19th-century conception of the anatomist Andreas Vesalius. Andrew Dickson White wrote of this image: “By the magic of [the artist’s] pencil Vesalius again stands on earth, and we look once more into his cell. Its windows and doors, bolted and barred within, betoken the storm of bigotry which rages without; the crucifix, toward which he turns his eyes, symbolizes the spirit in which he labours; the corpse of the plague-stricken beneath his hand ceases to be repulsive; his very soul seems to send forth rays from the canvas, which strengthen us for the good fight in this age.”Image: National Library of MedicineChapter 2 “One of the Glories of Our Race”

Just at this time, as it happened, a brilliant young historian at Michigan was beginning his search for the roots of this conflict. He was Andrew Dickson White, a graduate of Yale (and by sheer coincidence a member of Skull and Bones, Yale’s secret honorary society) who began his career at Michigan in the fall of 1857.

White was launching a career-long study that would lead to his two-volume masterwork, A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896, 1898). He searched libraries for every skirmish in this clash of ideas—debates on the origins of the universe, the evolution of animal species, the sources of weather, the shift from belief in magic to belief in chemistry and physics, to name only a few. He looked deeply into the Church’s long opposition to the study of anatomy, especially the use of dissection, and discovered why his medical colleagues had such trouble procuring specimens.

For many centuries, Christians reciting the Apostles’ Creed had declared their belief in an ultimate and literal “resurrection of the body.” The human form was regarded as the temple of the Holy Spirit, and if bodies were mutilated in death, the threat to resurrection on the Day of Judgment was obvious. Early Christian thinkers from Tertullian to St. Augustine opposed the study of anatomy as the work of butchers. In medieval times, ecclesiastical councils forbade both surgery and dissection on grounds that the Church opposed all shedding of blood. It was believed that one hidden bone in the body, “the necessary nucleus of the resurrection body,” was indestructible even by fire. Doubts dawned when a surgeon asked an executioner if any bone remained when a criminal’s body was cremated; the answer was no. But the abhorrence of dissection persisted.

The hero of Professor White’s chapters on anatomy was a Flemish surgeon of the 1500s, Andreas Vesalius. “The battle waged by this man,” White wrote, “is one of the glories of our race.”

At the risk of excommunication, Vesalius went to charnel houses for bodies, dissected them, studied them, and made detailed drawings of human structures. He published his Fabric of the Human Body at the age of 28. When Vesalius illustrated the body as it actually was, not as theologians thought it ought to be, a fracture appeared in the Church’s opposition to dissection. Here and there, papal dispensation was granted to European universities to take bodies apart.

Yet Vesalius was hounded and harassed for his troubles. When the authorities accused him of dissecting a living man, the charge—true or not—caused him to flee for the Holy Land. He was shipwrecked and drowned.

Vesalius’s death was a loss to religion as much as to science, Professor White wrote. “What was his influence on religion? He substituted, for the repetition of worn-out theories, a conscientious and reverent search into the works of the great Power giving life to the universe; he substituted, for representations of the human structure pitiful and unreal, representations revealing truths most helpful to the whole human race.”

Most of the human race, however, would be repelled by the idea of human dissection for several more centuries.

-

Chapter 3 Resurrectionists

Professor White’s scholarly studies might shed light on the deep cultural roots of the trouble. But that was little help to his colleagues over in the medical department, Professors Corydon La Ford and Moses Gunn. Those two had practical problems to solve, and the practicalities were getting more and more troublesome by the year.

Medical training had begun at U-M only in 1850. Until the Civil War, the number of students remained small. So most of the cadavers required could be gotten by legitimate means. In the poorhouses and prisons near Ann Arbor, there were always a few paupers and prisoners who died with no family or friends to pay for burial, and the authorities were willing to part with them. The professors embalmed them and stored them for dissection. If a shortage cropped up, quiet arrangements were made to secure “material” by less legitimate means. Sometimes these operations went undetected. Sometimes they led to the sort of incident that disturbed Christmas in tiny Cambridge Junction. But somehow the medical training muddled along.

Then, after the war, the medical department began to grow. Each incoming class of medical students swelled, and the demand for bodies kept pace.

Professors Ford and Gunn hired young assistants, often recent graduates, to help with instruction in anatomy and surgery. These men were called “demonstrators”—they demonstrated techniques in the laboratory—but their more important job was to go out and get bodies. They got as many bodies as they could legitimately. When the supply dried up, they stole them. Sometimes they did the work alone. More often they engaged in criminal conspiracies with men willing to rob graves for money.

These unsavory entrepreneurs were often known, with a gallows wink, as “resurrectionists.”

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

The building that first housed Michigan’s medical department (renamed the School of Medicine in the early 1900s), on the site now occupied by the Randall Laboratory. Dissections were conducted inside.

Each incoming class of medical students swelled, and the demand for bodies kept pace.

-

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

Professor Corydon Ford (center right) poses with anatomical “material,” anatomical demonstrators, and students.Chapter 4 “The Neighborhood of Dry Bones”

Moses Gunn, professor of surgery, was a firebrand. His views of life and death had been matter-of-fact since childhood. Once, as a small boy, he was building a little wagon when his big brother suggested that young Moses hitch the wagon to the family dog. No, said Moses, the dog was too old. In that case, the older boy said, with the cruelty common to big brothers, perhaps he would take the dog out and kill it. “If you’re going to kill everything that’s too old,” the younger boy retorted, “you’d better go in and kill Grandmother.”

His ironic edge was only sharpened by the Civil War, when he served as a field surgeon in General George McClellan’s Peninsular campaign. Gunn shook his head over the anonymity of surgeons at war. “Poor, benighted souls,” he wrote, “did anyone dream for a moment that a surgeon’s field had aught of glory about it? No, the glory consists of carnage and death. The more bloody the battle, the greater the glory.”

Soon after arriving at Michigan, Gunn began a running war with the Regents over his proposal to move the medical department to populous Detroit, where there would be many more patients to treat than in backwoods Washtenaw County. Finally Gunn grew so fed up that he not only decamped to a new post in Chicago; he also made off with the medical department’s entire supply of some 40 cadavers. When Michigan’s Board of Regents threatened legal action, Gunn called their bluff, saying they would never pursue him for fear of exposing the University’s traffic in the dead. He was right; the Regents backed down.

This left the task of resupply entirely in the hands of Gunn’s close friend and colleague, Corydon Ford.

Ford was an entirely different sort than Gunn. He was a quiet fellow who “feared nothing more than to do wrong,” according to a friend. Students and colleagues regarded him with deep respect and not a little sympathetic concern. Ford was a bachelor during his early years in Ann Arbor, and he was known to spend many solitary nights at work in the back rooms of the medical building, with only his silent specimens for company. When the anatomist married in 1865, former U-M President Henry Tappan wrote from Europe to congratulate him, obviously relieved that his younger friend would now have more congenial company in his leisure hours.

“I always thought your social and genial disposition peculiarly adapted you to the married state,” Tappan wrote, “and that you were calculated to make some woman happy, and that your own happiness would be increased by such a union. And now I suppose you are quietly settled in your own home… You no longer occupy the lonely room in the Medical College in the neighborhood of dry bones.”

However happy his new domestic life, Professor Ford still faced his chronic problem of supply and demand. In a letter to a sympathetic Regent with whom he could speak confidentially—Thomas Dwight Gilbert, of Grand Rapids—Ford complained about the rising expense and unseemly difficulties of acquiring cadavers. He said the medical department now needed at least 125 bodies every year. The costs were $20-30 per body, $5-10 for transportation and $2-3 for preservation fluids.

As demand rose, Dr. Ford’s demonstrator was forced to search all over the Middle West. The farther he ranged, the fewer his reliable contacts, and the greater the difficulty and risk.

“He cannot go into the field in strange places,” Ford told Regent Gilbert. “He must find men willing to undertake such illegal and dangerous work… Arrangements to escape detection must be made. After a body is received, it must be boxed, carted, and transported. All by unreliable persons who must be bribed!”

One of Michigan’s demonstrators in this era was Edmund Andrews. Years later, near the end of a distinguished medical career, Andrews wrote a sardonic memoir of his tenure as a resurrectionist.

“I found my duties peculiar,” he wrote. “The chief end of my official existence was to buy, steal, dig up, or in any other manner procure subjects for the dissecting room. To instruct the students was deemed meritorious, if I could get time for it, but by no means as important as getting the subject. Then the law was peculiar. I was a state officer charged with the duty of getting the material, but there was a statute consigning me to prison if I did my duty.”

This last point was perfectly true. The state required the University of Michigan to teach anatomy. But it also forbade the procurement of dead bodies for dissection.

Andrews nurtured relationships with the supervisors of “potter’s fields”—burying grounds for the unclaimed dead—and poorhouse cemeteries, mostly in Detroit and western Wayne County. He made it a rule to procure only out-of-towners, so that “the receiving point at Ann Arbor” might “be kept perfectly calm and friendly.

“It was pretty hard work at first,” he recalled, “and I had to get up 13 cadavers with my own hands the first winter. I was chased sometimes by constables but never caught, and I supplied the University.”

Clearly this could not go on forever, especially as the medical department continued to grow.

“Arrangements to escape detection must be made. After a body is received, it must be boxed, carted, and transported. All by unreliable persons who must be bribed!”

– Corydon La Ford -

Chapter 5 “The Only Satisfactory Solution”

In 1880, the latest round of public outrage over body-snatching fell squarely on the head of the current demonstrator in anatomy. William James Herdman had held his job for five years. Sick and tired of being cast as the devil in this long-running drama, Herdman decided to lay the whole business on the table and make a plain case for reform.

“I do this,” he wrote in a long memorandum to the Regents dated June 28, 1880, “in the hope that the subject will receive careful and considerate deliberation at your hands, and that the difficulties which beset me, in the duties you have assigned to me, will be appreciated, and from you I will receive sympathy, friendly advice and counsel instead of that wholesale abuse and criticism which it has become the fashion to heap upon me…

“As far as we are able to secure our supplies from other colleges it relieves us from the charge of direct depredations in our own immediate vicinity. But these sources of supply have always been exceedingly precarious, at one time yielding abundantly and at another failing utterly in the time of our greatest need. Moreover, we have no security whatever [that] what is sent us has not been secured in the most unlawful manner, and, if traced to us, and discovered here, it is upon our innocent head that the public indignation is poured out and not upon those whose love of money has induced them to commit the crime.”

To meet the demand for cadavers, he said, “I have labored early and late and have tested every honorable method.” He had resolved “to exhaust all strictly legal sources of supply before resorting to any other means; to complete the supply from the surplus at other colleges, if possible; when necessary…to draw from the pauper and friendless dead at our County-houses and asylums with the consent of the proper authorities if such consent could be obtained.” But it was never enough.

Ohio, Indiana and Illinois had all passed new laws requiring anatomical donations, he said, and older laws were operating in New York, Pennsylvania and Missouri. Why not Michigan?

Herdman and his colleagues had pressed for new rules to make it compulsory for poor houses and prisons to give unclaimed bodies to the medical department, but no such provisions had been made. One satisfactory bill had cleared the state House, then failed in the Senate. “A bill of this nature has the disadvantage of being very easily misunderstood, and being tainted with rather unpleasant associations; is shunned and feared unless attention can be secured for it by the respectability and prominence of its advocates.”

The solution, Herdman wrote, was “the friendless pauper.”

“Now, I do not, as has been frequently charged against me, lack sympathy for the pauper class in our community. Neither do I regard the body of the pauper any better suited for anatomical study than that of the millionaire. But the pauper has been the ward of the State or County, he is maintained at public expense, he is attended in his last illness by medical skill at public expense, and his funeral unattended by mourning friends and relatives is a charge that the public has to meet. Is it therefore asking too much that his body, unclaimed by friends, cared for by none, useless to himself, be made to contribute to the welfare of his fellows who have given freely of their substance to provide for him in comfort and health during his natural life?”

He had done his best to meet the need, but it was well nigh impossible. He faced “the difficulty of keeping myself informed as to the time when such deaths occur, the horror of officials in charge at the thought of being detected as accomplices in such ‘horrible business,’ the scarcity of reliable agents to secure such bodies and leave all others undisturbed, the impossibility of knowing whether my instructions—always clear and explicit—have been faithfully regarded.” The Regents would certainly not be shocked to learn that occasionally “the grave of a respectable citizen has been ruthlessly disturbed.” No wonder, given “the character of many of the men we are compelled to employ in this clandestine business.” Yet “the University and myself are made the unfortunate victims of their unscrupulous greed… Michigan University or its Demonstrator of Anatomy is not responsible for all the graves robbed of their contents from Maine to the Mississippi River and from the Lakes to the Gulf… Yet the public press and public opinion point the finger of suspicion at us…”

With all these factors against him, Herdman said, he was now desperately short of anatomical materials. He had cadavers on hand for perhaps one out of ten students in the new class expected that fall.

It was now up to the Regents to demand a better solution from the state officials who insisted on the proper teaching of anatomy. “This is the only satisfactory solution that presents itself to my mind for this grave (robbing) problem.”

Herdman’s plea struck home, and it helped the cause of medicine if not of Michigan’s “pauper class.” An act approved by the very next session of the state legislature directed that “the bodies of deceased who had been supported in whole or in part at public expense in any county or state institution, should be, if unclaimed by a relative or legal representative, forwarded to the demonstrator of anatomy of the University of Michigan.” That individual would then distribute the cadavers among his own department, the Detroit Medical College and the Michigan College of Medicine in proportion to their numbers of students.

It was the compulsory donation of “the pauper dead” that Herdman had begged for.

Michigan’s graveyards were restored to silence.

-

enlarge

enlarge

Caption

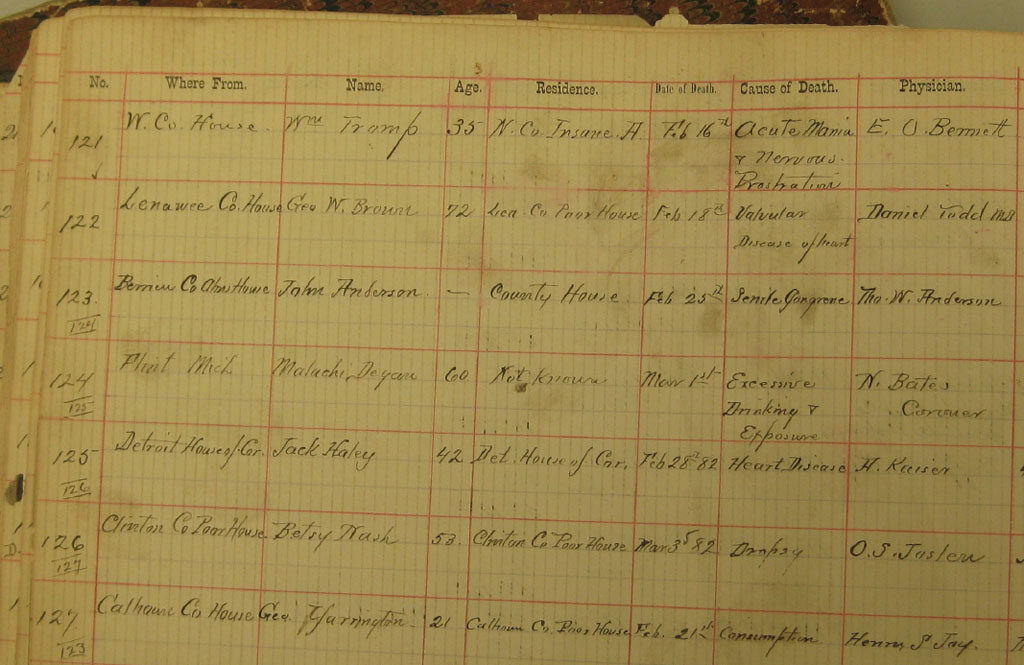

A page from the University’s anatomical registry of 1881 shows typical sources: The Detroit House of Correction; the Berrien County Almshouse; the Clinton County Poor House. Causes of death include “acute mania and nervous prostration,” “senile gangrene,” “excessive drinking & exposure,” and “consumption” (tuberculosis.)Chapter 6 Epilogue

The men associated with the higher levels of Michigan’s commerce in cadavers all went on to distinguished careers.

Professor Moses Gunn was chair of surgery at Rush Medical College in Chicago until his death in 1887.

The anatomy demonstrator Edmund Andrews, who dug up thirteen bodies by himself over the course of one Michigan winter, served as surgeon to the First Illinois Light Infantry in the Civil War, professor of surgery in the institution that became the medical school of Northwestern University, and president of the Illinois State Medical Society.

The anatomy demonstrator William James Herdman joined the faculty as a professor and became Michigan’s first neurologist, then its first psychiatrist. He also founded the program in electrotherapeutics, the branch of medicine that first used electrical current to treat disease and disability.

Professor Corydon La Ford remained on Michigan’s faculty for forty years. He and his wife left $20,000—a sizable endowment in that era—to the University Library.

And the historian Andrew Dickson White, who anatomized the war between science and religion, left the University in 1863, was elected to the legislature of his home state of New York, and soon became the founding president of Cornell University.

Michigan’s Anatomy Act of 1881, many times amended and improved, led to the modern regime under which bodies are donated (never sold) under tight regulation. Annual memorial services are held to honor the contributions of the dead. Today, many generous individuals donate their bodies each year to help U-M medical students, dental students and many others learn human anatomy. They are assured of respectful treatment and the opportunity to have their cremated remains returned to loved ones or interred in a special U-M burial plot.

This article was drawn from the papers of the School of Medicine, Bentley Historical Library; Linda Robinson Walker, “Grave Subjects: The Birth of the University of Michigan Medical School,” Michigan Today (Fall 1999); Robert Kedzie, “The Early Days of the Medical Department,” and Henry M. Hurd, “The Medical Department in 1865,” Michigan Alumnus, February 1902; “Body Snatching,” Ann Arbor Local News and Advertiser, 12/29/1857; Donald F. Huelke, “The History of the Department of Anatomy, the University of Michigan, pt. 1, 1850-1894” (U-M Medical Bulletin, January-February 1961); C. B. G. De Nancrede, “Address Delivered on Founder’s Day” [regarding Moses Gunn], Michigan Alumnus, 5/1/1906; Ruth Richardson, Death, Dissection and the Destitute (1987); Andrew Dickson White, A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom (1896, 1898); C.B. Burr, ed., Medical History of Michigan, vol. 1 (1930); “The Resurrectionists,” Medicine at Michigan (Fall 2008).